Johnston is Turned

from ATLANTA WILL FALL, published by Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., appears by permission of the publisher

Sherman knew he would have to flank Joe Johnston. "To strike Dalton in front was impracticable," he later wrote, because of the inaccessible ridge, the Rebels' fortifications, and the by-now widely understood axiom, shared by commanders on both sides, that prepared defenses are impervious to frontal assaults. Moreover, as one of Thomas's scouts reported in early April, the Southerners had dammed up Mill Creek and flooded the gap basin to impede an infantry advance. In the early stages of his planning (around April 10), however, Sherman thought not of using Snake Creek Gap (Thomas's idea) but of making a wider arc around Johnston, sending McPherson's Army of the Tennessee, then at Huntsville, across the Tennessee River by pontoon at Decatur and Whitesburg, Alabama, and marching toward Rome (about forty miles south of Dalton) to cross the Coosa River and so outflank the Rebel army. By late April, when it appeared he would not get all the divisions he wanted for McPherson's army--he had hoped for nine divisions, 30,000 strong--Sherman considered such a wide detachment too risky and determined to keep McPherson closer in, flanking the Rebels by way of Snake Creek Gap, after all. But as a big modification of Major General Thomas's plan, Sherman designated McPherson's army, not Thomas's Army of the Cumberland, as the flanking force. While McPherson maneuvered, Sherman's plan called for Thomas and Schofield to keep Johnston pinned and focused on his front.

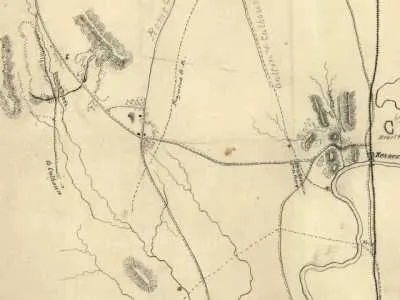

General Johnston could hardly have been unaware of the enemy's intentions. As hard as he hoped for a blundering frontal attack against Rocky Face Ridge, the Confederate commander must have doubted that his Northern opponent would be so obliging and stupid. As early as late February, Longstreet had warned Johnston, "If you don't try some flank movement, the enemy will, and throw you out of position." Johnston's chief of staff, Brigadier General William W. Mackall, similarly recorded in early March his prediction that the Yankees "would try and go past Dalton." To prepare for such movements, Johnston had his topographical engineers mapping the whole area around Dalton. Captain F. R. R. Smith, for instance, was ordered to survey and map an area well to Johnston's right flank, fully ten miles east of his position along Rocky Face. Smith was at work on this exercise when he was captured, April 13; his orders and maps all fell into Union hands.

On his other flank, Johnston had good maps as well. We know today that maps carried by Confederate Brigadier General Henry D. Clayton (whose brigade was in A. P. Stewart's division, Hood's corps) showed the area from Red Clay, on the Tennessee border, to Tilton, well south of Dalton. Ridges, gaps, roads, and streams were well marked on those charts; one in particular shows the course of Snake Creek (though unnamed) through Rocky Face, ten miles southwest of Dalton. Johnston therefore knew of the ridge gaps beyond his left flank. Wheeler had his cavalry picketing a wide front, from Ship's Gap in Taylor's Ridge on the left to the Conasauga River far to the right. The Confederate commander, in other words, had at least an adequate if not fully ample intelligence network in place when Southern scouts detected enemy troops on the march in the first days of May. On the 3d, dispatches sent in by Wheeler's scouts led Confederate staff officer Lieutenant Thomas B. Mackall to record, "preparations for movement on part of enemy [are] universally "preparations for movement on part of enemy [are] universally confirmed."

The next day, May 4, Sherman ordered his three armies on the march early. Thomas moved on Ringgold while Schofield advanced on his left. McPherson's Fifteenth and Sixteenth Corps were well to the rear, leaving north Alabama and heading past Chattanooga toward Rossville. Sherman was pleased and confident. He had reason to be: after a winter of planning, his forces were on the move, well supplied and very strong (they would get stronger still, once the Seventeenth Corps, en route from the Mississippi Valley, joined McPherson's army). What was more, Johnston was doing nothing, save for the usual light skirmishing by Confederate cavalry in Schofield's and Thomas's fronts. "Everything very quiet with the enemy," Sherman recorded on the night of the 4th. "Johnston evidently awaits my initiative." Thus, on the opening day of the campaign for Atlanta, the three decisive elements shaping the campaign's outcome--Sherman's aggressiveness, superior Northern numbers, and Johnston's passivity--were already evident.

The Federal plan unfolded in the next three days. Thomas and Schofield were to press down upon the Rebel positions along Rocky Face, diverting Johnston's attention from McPherson's turning maneuver to the south. Late on May 5 Sherman gave his good friend Mac orders for what he hoped to bring about: "I want you to move ... to Villanow; then to Snake [Creek] Gap, secure it and from it make a bold attack on the enemy's flank or his railroad at any point between Tilton and Resaca." If Johnston retired, he continued, "you will hit him in flank. Do not fail in that event to make the most of the opportunity by the most vigorous attack possible." If Johnston stayed at Rocky Face, slugging it out with Thomas, McPherson could descend on the Western & Atlantic in the Rebels' rear, wreck it, then retire westward to await the issue of battle to the north.

On the 5th Thomas pushed closer to Tunnel Hill; McPherson, with by far the longer route, moved his troops south of Chattanooga. Over in Confederate lines, General Johnston tracked these developments, but he did not know which flank to fear for most, his left or his right. Lieutenant Mackall, the staff officer, noted, "Scouts think attack will be made on our right.” At the same time, however, Johnston suspected the possibility of a wide enemy flanking march by McPherson toward Rome. On the night of the 5th Generals Johnston, Hood, Hardee, and Wheeler conferred at length at army headquarters, trying to divine Sherman's plans.

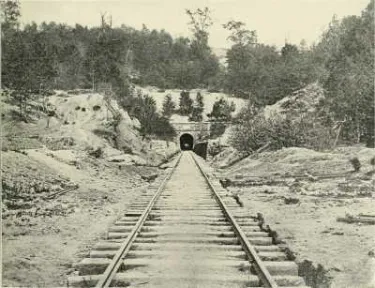

They were about to unfold. Though behind schedule, the head of McPherson's army camped at Lee and Gordon's Mill on the night of the 6th, and on the 7th moved to the southeast of Rock Springs Church en route to Ship's Gap. By then, Thomas had taken Tunnel Hill with little opposition--General Sherman seemed surprised that the Rebels had not tried to injure the critical railway tunnel--and begun skirmishing with the Rebels at Buzzard Roost. As he advanced on Rocky Face, so did Schofield's Twenty-third Corps, having advanced from Red Clay to cover Thomas's left flank. For the 8th, Sherman directed his army leaders to do more of the same: Schofield to feel down on the enemy, moving south-west from Varnell's to the northern reaches of Rocky Face; Thomas to threaten Mill Creek Gap but "not to lead to battle unless the enemy comes out of his works"; and McPherson to march by way of Villanow to occupy Snake Creek Gap. All three objectives were accomplished on the 8th. In the process there occurred the "Battle of Dug Gap" (the first "battle" of the campaign deserving of the name), in which Brigadier General John W. Geary's division pressed hard against the Gap, defended at first by only a thousand Confederates, who were soon reinforced. In the end, Geary withdrew, leaving Johnston still in possession of the Mill and Dug passes.

The seven infantry divisions of the Army of Tennessee were, as Lieutenant Mackall wrote, “all in hand for off[ense] or def[ense]” in an entrenched seven-mile line running from east of Dalton (Patrick R. Cleburne's division) to south of Mill Creek Gap (B. Frank Cheatham and W. H. T. Walker). Johnston knew Sherman's army stretched from Varnell's to below Trickum, and, from the repulse of Geary's assault at Dug Gap, he knew that there was likely still more danger farther to the left. After reporting some of McPherson's troops way to the west near LaFayette (headed for Rome?), Wheeler's cavalry was ordered to be on the lookout well to the south. A Confederate infantry brigade at Resaca under Brigadier General James Cantey (the first reinforcements to Johnston's army from Alabama) was also instructed to "keep close observation on all routes leading from LaFayette to Resaca or to Oostenaula." Johnston warned Polk, who was moving toward Dalton from Alabama, that McPherson could be headed for Rome. Then the Southern vedettes seem to have lost contact with McPherson; on the 8th Johnston' s headquarters received no word of his whereabouts. When Lieutenant Mackall recorded news of "Hooker's Corps crossing Taylor's Ridge this morning [May 8] at Ships Gap & Gordon Spgs Gap," the Southerners were confusing the Twentieth Corps with McPherson's column. General Cantey on the 8th wired from Resaca that cavalry scouts reported "Yankees in vicinity of Villanow today," but he could not identify their units. Nevertheless this movement toward Villanow--which McPherson reached that afternoon at two o'clock--was enough to concern Johnston's staff. Confederate cavalry under Colonel J. Warren Grigsby, having helped repel Geary at Dug Gap, was ordered to Snake Creek Gap that night. But there is nothing in the Confederates' correspondence to indicate their awareness that Grigsby's small brigade, fewer than 500 strong, was being sent against two corps of Yankee infantry, already entering the Gap.

Had Sherman known this, he would have been less concerned for the safety of McPherson's column. As it was, though, he worried that Johnston was taking troops from his main line and shifting them southward to jump McPherson. "The reconnaissance to-day has not drawn a single gun of the enemy," he complained to Thomas on the night of the 8th. "I fear Johnston is annoying us with small detachments, whilst he will be about Resaca in force." The same message went to Schofield at midnight: "We must not let Johnston amuse us here by a small force whilst he turns on McPherson." Sherman therefore ordered Schofield the next day to "keep up the idea of an advance," with skirmishers to "act with boldness, but not rashness" to discern the enemy's strength in position. Thomas also planned demonstrations along Rocky Face beginning at six in the morning, which, with Schofield's, succeeded in arresting the Rebels' attention.

If Sherman was concerned about locating the enemy army's main position, so was Johnston. Early on the 9th he instructed Wheeler to find out whether most of the Yankees were north of Rocky Face, or west of it; Wheeler's reconnaissance led to a run-in with Edward M. McCook's cavalry on Schofield's left, in which the Northerners received the worst of it. But by 10:00 A.M. Confederate headquarters turned eyes to the south, as word came in that Grigsby's troopers had encountered enemy forces at Snake Creek Gap. They were infantry of Brigadier General Grenville M. Dodge's Sixteenth Corps, leading McPherson's column, emerging from the southern opening of the Gap, fanning out. All Grigsby could do was retire fighting and call for help. Advancing eastward toward the railroad, Dodge not only pushed back the Rebel horsemen but routed a little group of maybe a thousand infantry, hastily assembled on a hill a mile west of Resaca. That place, with the vital rail-road was now in McPherson's reach. Mac wrote back to his commander at 12:30 that he proposed to cut the railroad, then according to his orders on the 5th fall back to a defensive position and await developments from Thomas and Schofield's front. McPherson was dearly worried that there were sizable enemy infantry before him. He had insufficient cavalry for scouting, and, besides, he had not established communication with General Hooker to the north (Thomas's right), who might warn him of a sudden enemy shift southward against him. For these reasons McPherson's advance probed tentatively toward Resaca, drawing fire from Rebels holed up in a fort overlooking the Oostanaula railroad bridge, and others well dug in (Cantey's brigade, Grigsby's tired troopers, as well as a Georgia regiment and battalion stationed at Resaca). The Southerners' stout resistance, coupled with McPherson's mounting uncertainty, led him after several hours of skirmishing to order Dodge's men to retire back toward the Gap, which they did by dark. Later, somewhat lamely, Mac told his friend Cump, "If I could have had a division of good cavalry I could have broken the railroad at some point." As it was, McPherson's forces disturbed not a single track of the Western & Atlantic that day, and the only damage done, by some mounted infantry near Tilton, was to snip the Rebels' telegraph wire.

Both sides blundered on May 9. McPherson, having made a dramatic, surprise flanking march on Johnston, succumbed to his fears in not striking harder against the small enemy force holding Resaca. Similarly, Johnston at his headquarters in Dalton reacted just as tentatively and passively to the dangerous threat on his south flank. He, too, suffered from a lack of sure information. While Wheeler was earning accolades in the northern sector driving back Yankee troopers, his cavalry could have been engaged with Dodge, developing the enemy's strength and intent. At the same time, Johnston was remarkably lethargic in calling for more vigorous scouting of the Villanow-Snake Creek Gap sector. Throughout the several days Johnston seemed oddly oblivious to the crisis brought on by McPherson's march. "I do not think Resaca is in danger," Mackall, Johnston's chief of staff, wrote at 4:00 P.M. on the 9th; "we have 4,000 men there." Informed as early as May 5 of enemy infantry marching southward by way of Lee and Gordon's Mill, Johnston thought Rome might be their objective. On the 6th this column was identified as Logan's corps. But after the 7th, when the Confederate high command fixed part of McPherson's army near LaFayette, Johnston seemed willfully to ignore McPherson, or hopefully to assume that Polk’s troops arriving from Alabama could concentrate at Rome and so meet the threat. As a result, Johnston’s only response was to send a weak cavalry brigade to Snake Creek Gap which, no surprise, found massed Yankee infantry marching through when it arrived on the morning of the 9th.

Thus, notwithstanding Johnston’s understandable preoccupation with his Rocky Face front (as Sherman hoped), given the threat to the safety of his army posed by a strong enemy column marching beyond his flank and threatening his railroad and rear, Johnston must be blamed unequivocally for a huge tactical blunder. What response he made during May 7-8, the critical days of the enemy turning movement, was completely inadequate. As the threat to Snake Creek Gap developed, Johnston moved no infantry from his line. His hope that Polk, expected to arrive at Rome on May 9, might help meet the threat was unrealistic, as was the idea that 4,000 men assumed to be at Resaca could prevent McPherson from cutting his vital supply line to the rear.

General Johnston’s apologists have steadfastly refused to impute negligence or blunder to the Confederate commander. In most of their writings Major General Wheeler has taken the blame. Chief of Staff Mackall led the way by spreading talk that someone (presumably Wheeler) was guilty of a “flagrant disobedience of orders.” To be sure, beginning May 5, General Mackall had conveyed to Wheeler the commanding general’s wish that cavalry bring in “the most accurate information” on enemy positions east of Taylor’s Ridge. The next day, Lieutenant Mackall privately recorded, “Not a thing has been ascertained by Wheeler’s cav—inactive….But few scout reports rcd. from Gen. Wheeler—generally unsatisfactory.” Yet for a long while afterward the Confederate leadership puzzled over whom to blame for the failure to guard Snake Creek Gap.” How this gap, which opened upon our rear and line of communications, from which it was distant from Resaca only five miles, was neglected I cannot imagine,” Major General Patrick R. Cleburne wrote several months later. “Certainly the commanding general never could have failed to appreciate its importance.”

Johnston’s biographers have accepted Cleburne’s supposition and accused Wheeler and his troopers of faulty scouting of McPherson’s movements. Gilbert E. Govan and James W. Livingood say, “The evidence points to the cavalry as the source of failure.” Craig L. Symonds echoes their analysis: “Johnston’s uncertainty about Federal intentions was largely a product of the weakness of his cavalry—the eyes of the army.” Students of the Atlanta campaign strongly supportive of Johnston accept Mackall’s charge that Wheeler acted irresponsibly. An early writer, Wilbur G. Kurtz, concludes: “Johnston was a victim of…overweening reliance on subordinates who were derelict in duty.”

As if to exonerate both Wheeler and Johnston, however, others have suggested that Snake Creek Gap never appeared on the Confederate maps that the army used—a claim that, as the topographical maps in Brigadier General Clayton’s possession show, cannot be supported.

Still, other commentators have wondered whether it was Johnston, not Wheeler, who was derelict. Former National Park Service historian Edwin C. Bearss, for instance, asked himself why Johnston, trained in topographical engineering in the old army, could have been so blind to the importance of mountain passes on his southern flank. The characteristically outspoken Thomas Lawrence Connelly, even acknowledging the drawbacks in performance of Wheeler's cavalry, resolved that "Johnston completely ignored Snake Creek Gap, and made no inquiries as to its status." Nevertheless, Johnston's champions and critics agree that in Round One of the Atlanta Campaign, Sherman outgeneraled Johnston. Sherman knew immediately. "I've got Joe Johnston dead!" he exulted on the afternoon of the 9th, when word came in that McPherson was closing in on Resaca. Early the next morning he wired Washington: "I believe McPherson has destroyed Resaca," breaking Johnston's line of communications. The Union commander began thinking through various plans by which he could capitalize on McPherson's success, well aware, as he related to General Halleck, "Johnston acts purely on the defensive." As a good army leader has always been enjoined to do, Sherman early on May 10 planned to reinforce success: build on McPherson's flanking maneuver by throwing the bulk of Thomas's strength around Johnston by the same route so that he might "swing round through Snake Creek Gap, and interpose between him and Georgia." Johnston would try to retreat; then McPherson could attack the Rebels in flank. No wonder he believed he had Joe Johnston dead!

Mid-morning on the 10th, however, by 10:30, General Sherman received McPherson's dispatch of the night before and learned that the Army of the Tennessee had failed in its mission. "I regret beyond measure you did not break the railroad, however little," he wrote McPherson back, "but I suppose it was impossible." (Three days later, when the two officers met, Sherman is said to have told his friend, "Well, Mac, you have missed the opportunity of a lifetime.") There was no time, however, for lamenting the lost opportunity. Sherman instructed McPherson to dig in where he was, await reinforcements (Hooker's corps), and resist any Rebel attack until Thomas and Schofield could march to meet him. In the meantime, Howard's Fourth Corps, helped by McCook's and Major General George Stoneman's recently arrived cavalry, would stay behind, keeping up enough of a demonstration against Rocky Face as to distract Johnston from the main movement. At his headquarters in Dalton, General Johnston was finally alive to the enemy's turning movement. Having impressed upon Cantey the "absolute necessity" of holding his position at Resaca and the railroad bridge across the Oostanaula, having dispatched a brigade of reinforcements to Cantey, and having received positive reports that the enemy moving on Resaca were Dodge's and John A. Logan's corps (though Cantey and cavalryman Will Martin still said Hooker), Johnston on the night of the 9th ordered General Hood to take Cleburne's, Walker's, and Hindman's divisions to Resaca. Thus would begin the army's withdrawal from Rocky Face back to Resaca, where presumably it would again take up defensive positions. (Johnston also sent his chief engineer, Major Stephen W. Presstman, to stake out works around the place.) Arriving there, Hood found that McPherson's forces had withdrawn to the west, and he wired Johnston, "R[esaca] all right Hold on to Dalton." Indeed, later that day Hood returned to Dalton with one of the divisions because the threat to Resaca, for the moment at least, appeared to have abated. Besides, the first of Loring's divisions arrived at Rome on the 10th, assuring Johnston that reinforcements would be coming by rail through Resaca itself. Johnston told Polk to concentrate there and assume command.

With McPherson digging in, Sherman, skirmishing with Rebel cavalry but showing neither boldness nor haste, pushed his plan forward. He had stolen a march on Joe Johnston, as he told Halleck, and therefore he would be in no hurry to swing the rest of his forces southward. Accordingly, Thomas and Schofield slowly shifted by the right flank during May 11-12, so that by night of the 12th, five of Sherman's six corps were at Snake Creek Gap (Howard's Fourth would bring up the rear). Johnston became aware of their movements. To Polk at Resaca, Mackall on the morning of the 12th wired, "The enemy in our front is moving rapidly down the valley toward Snake Gap or Villanow." Wheeler's reconnoitering around the north end of Rocky Face confirmed most of the Yankees gone. Hence, in late morning Polk received a stronger message from headquarters: "The enemy seem to be abandoning this place." Although unsure of his opponent's precise objective (Resaca, Rome, or, now, Calhoun?), Johnston knew for certain it was time to leave Dalton. After telegraphing Richmond that the enemy was heading for the Oostanaula and that he intended to follow, the commanding general left Dalton by train on the evening of the 12th. The rest of the army, at least that part not already at Resaca or on its way thereto, evacuated in the night.

This material is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Please contact the publisher for permission to copy, distribute or reprint.

Your gift today helps save 77 acres at Ringgold Gap, Rocky Face Ridge, and Kennesaw Mountain — where history was made — with an incredible $22-to-$1...