War is filled with turning points large and small. Some constitute great tides of history. More of them mark subtle changes in momentum or policy that reverberate in their own way. On May 1, 1863, on often-overlooked lands east of Chancellorsville, the Civil War took one of those turns, commencing a bloody tide of events that would climax two months hence at Gettysburg.

The bright aura that surrounds the army of Gen. Robert E. Lee often obscures just how dark was the Southern nation in the months before the Battle of Chancellorsville. Discord over emancipation in the North was eclipsed by anger at it in the South. Confederate defeats in the West had mounted. Riots over bread filled the streets of Richmond.

Along the Rappahannock River, Robert E. Lee and his army shone as a lone beacon for the struggling Confederacy. But even in that chronically victorious army, soldiers sensed that the war had become, at best, a grinding ordeal that would produce victory only at great cost. A soldier from North Carolina wondered, “We must be successful in the end, but when will the end be?” He marveled at the Yankees’ determination in the face of defeat and winced at the ordeal ahead. Still, he wrote, “I am not at all discouraged…. I would not accept a discharge from the army now, if it was given me.”

North across the Rappahannock, the Union army hovered, led by a new commander and emerging from a gloom imposed by humiliating defeat at Fredericksburg in December. Hope for the spring resided in that new commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. He was a man whose path to power was unlike any of his cohorts’ and whose combative reputation promised much to an army unused to being used both wisely and aggressively.

People rise in organizations for many reasons. We all know the types. Those we admire most — men like Ulysses Grant, Robert E. Lee, Dwight Eisenhower, “Stonewall” Jackson, George Marshall — rise simply due to their own excellence. Some talented people, like George McClellan and Douglas McArthur, mottle their legacy by engaging in self-advocacy. Rarer still were men like Hooker. He used carefully cultivated contacts within Congress and the administration not just to promote his own accomplishments (a fairly common thing), but to diminish the accomplishments and reputations of others. Hooker explained his penchant for intrigue in patriotic terms. He was, he wrote, “pronounced in my opinions…for the sake of the cause and the country…simply to have the attention of the authorities called” so that “mistakes might be remedied.”

Few others saw his efforts in so noble a light.

Beyond his politicking, Hooker owed his rise in the Army of the Potomac to one dominant characteristic: aggressiveness. In an army peopled by cautious men and possessed of a cautious culture (a legacy of McClellan), Hooker had a fighting record splotched with spectacular spasms of aggression. Indeed, most of his cohorts saw him as aggressive to the point of carelessness. Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny — himself combative beyond most — deemed Hooker thoughtlessly bellicose. And Maj. Gen. George Meade, who liked and admired Hooker in some ways, wrote, “I should fear his judgment and prudence, as he is apt to think the only thing to be done is to pitch in and fight.”

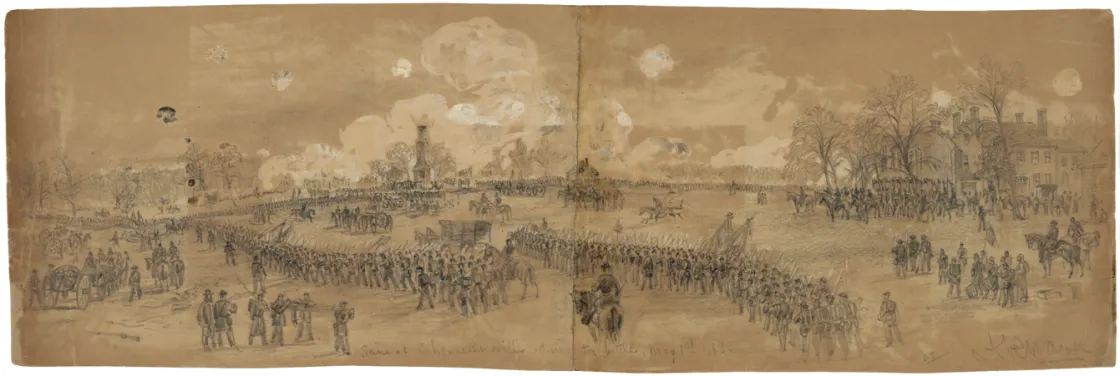

Such sentiments and expectations sailed to the background on the evening of April 30, 1863, as the vanguard of Hooker’s army pulled into the clearing at Chancellorsville — the home of Frances Chancellor and her seven children. Four corps of Hooker’s army had managed a startling success. Leaving their camps in Stafford County, they had arced northwest, west, and then south, across first the Rappahannock and then the Rapidan River to plant themselves firmly on the left flank of Lee’s position. And by all appearances, Lee had little idea Hooker was there.

Rarely had the army been in such a position — and men from lowly privates to major generals sensed it. One man from New York wrote home, “Hooker[‘s] stock is rising. He furnishes the brains, the Army the legs, and I think the legs have won.” Brig. Gen. A.S. Williams, commander of a division in the XII Corps, remembered the reverie: “Everybody prophesied a great success, an overwhelming victory….We began to think we had done something heroic.” Hooker caught the moment, too. He issued an order declaring success — that Lee’s army “must ingloriously fly” or march out to fight on ground of Hooker’s choosing.

Hooker’s flank march to Chancellorsville surely surprised Lee and constituted a Yankee accomplishment, but much work remained for the Union commander to achieve his ultimate goal of Lee’s defeat. Lee, of course, would have his say in the matter, too. On April 30, he faced a complicated landscape. Two-thirds of the Union army had crossed above his left. Thousands more men still occupied the heights opposite Fredericksburg and threatened to cross the Rappahannock there, too (indeed, they soon would) — creating a 16-mile-wide vise that threatened Lee from two directions. Lee decided the Union column at Chancellorsville posed the greater threat. Putting his faith in the Union culture of caution, he left just a small force at Fredericksburg. With the rest of his vastly outnumbered army, he marched toward Chancellorsville. Lee, the man of action and initiative, was forced to react to a man (Hooker) who firmly held both the initiative and a superior position.

On the evening of April 30, Union cavalry and infantry pushed beyond the Chancellorsville crossroads, emerging from the tangled Wilderness, hunting east along the Orange Plank Road and the Orange Turnpike. Hooker made his headquarters at the Chancellor House, where the family and a group of refugees from Fredericksburg had retreated to the basement. Reports, and perhaps his own observations, surprised him. The vaunted “Wilderness of Spotsylvania” that surrounded Chancellorsville was every bit as tangled and daunting as advertised, pierced by few roads and pocked with smallish clearings. It took him until 11:00 a.m. the next morning, May 1, to prepare himself and his army for an advance. By then, Lee was already well on the way to confronting him east of Chancellorsville.

Hooker’s plan called for his army to move eastward out of the Wilderness along three roads. Part of Meade’s V Corps would take River Road, closest to the Rappahannock. A division of the V Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Sykes and largely made up of Regular Army veterans, would lead the way directly east along the Orange Turnpike. And Maj. Gen. Henry Warner Slocum’s XII Corps would move first south, then east along the Orange Plank Road, on the army’s right. The army’s front spanned six miles north to south, all told about 70,000 men. A mile to the east of Chancellorsville, the Wilderness abruptly ended, there the turnpike descended into the valley of what was then known as Mott’s Run (today called Lick Run). From there, east toward the heights at Zoan Church and Fredericksburg beyond, the ground was vastly more open — a landscape suited to the maneuver of armies.

That May 1 morning, Lee’s Confederates started piling up on the roads heading west from Fredericksburg toward Chancellorsville. Parts of two Confederate divisions would do most of the fighting this day. On the Orange Turnpike stood the division of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, holding the line at Zoan Church. Maj. Gen. Richard Heron Anderson’s division stood to McLaws’s left, extending the line from the turnpike south to the Orange Plank Road. Anderson’s lead brigade, led by Brig. Gen. William Mahone, had skirmished with Hooker’s vanguard on the Turnpike the night before. Lee’s directive to McLaws and Anderson, ordering them to hold the line at Zoan Church at all costs used some dramatic language to convey his intent: “It must be Victory or Death, for defeat would be ruinous.” Behind Anderson marched Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s column, angling slightly southward along the Orange Plank Road, toward Tabernacle Church and Slocum’s column.

When Jackson arrived on the field about 8:00 a.m. on May 1, he decided not to wait for Hooker to come to him. Instead, he ordered Anderson and McLaws to advance from the ridge at Zoan Church on the turnpike. Meanwhile, Jackson would move his column west on the Orange Plank Road, on McLaws’s left. The idea was simple but effective: if Yankees moved east on the turnpike, McLaws and Anderson would confront them directly while Jackson’s men fell on their right flank. Jackson would meet Hooker’s aggression with his own.

About 11:00 a.m. Virginians of Mahone’s brigade (north of the turnpike) and Brig. Gen. Paul Semmes’s Georgians (south) swept down the slope west of Zoan Church. Union cavalry videttes stood only a half-mile west, and Mahone’s men quickly dispatched them. In front stood open ground, dotted by a succession of small farmhouses, at least a few of them owned by Union sympathizers. In the yard of Ann Lewis’s house near Mott’s Run lounged men of the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry, constituting the eastern edge of Hooker’s picket line that morning. Warning of the Confederate advance came to the commander of the 8th Pennsylvania from his hostess, who excitedly called him upstairs to “look at the rebels.” The colonel dismounted his horseman and formed a rough, hasty line of battle just east of Mrs. Lewis’s place. Mahone’s men quickly closed upon them.

The Pennsylvanians could not and did not hold long, but they bought precious minutes. As the Union cavalry eventually tumbled back across Mott’s Run, the welcome sight of Hooker’s main column appeared astride the turnpike on the heights above them. Neither Joseph Hooker (still back at Chancellorsville) nor George Sykes, commander on the ground, expected Confederates in force so soon. Questions swirled. How many? What did it mean? Sykes could get answers only by pushing ahead.

Sykes’s lead brigade, commanded by Col. Sidney Burbank, formed a line astride the turnpike five regiments wide, probably nearly a half-mile long. The Regulars had to struggle through marshy, brushy ground along Mott’s Run. They scattered some of Mahone’s men around the farm of Reuben McGee, then pushed on, but more of Mahone’s men awaited. The diminutive, bearded, combative Virginian formed his line just east of the Joseph Leitch House, defining what would soon become the eastern edge of the Chancellorsville Battlefield.

From west to east Burbank’s men moved — those to the north of the road in panoramic array, those to the south largely obscured by woods. Shells from a Confederate battery 600 yards off pelted them all. “The impulse is irresistible to duck,” wrote a Union surgeon, “and the whole line bows frequently.” The Federals passed Mrs. Lewis’s house and the slight ridge upon which it sat, then descended again, preparing to ascend the ridge that was home to the Leitch family—the fighting place of Mahone’s men. The Federals came under fire at 200 yards, and then struggled forward to within 75 yards of the Virginians before the intensity of bullets convinced them that more bravery meant only more death. The Federal line fell back to the reverse crest of the Lewis House ridge. “The men remain fierce,” one Regular told his wife, “there is no confusion, but also no enthusiasm[;] not a cheer responds to the howling of the Rebels.” One of those Rebels called it a “fair, square stand-up, open field fight.”

For all its mayhem, this initial clash brought both clarity and rapid response from each side. To Jackson, the clash signaled Hooker’s aggressive intent. To Sykes — and eventually Hooker — battle so soon portended ill. Both sides rushed reinforcements into the battle. Sykes dispatched word to Hooker, asking that his position be bolstered. On the field itself, Sykes sent another brigade of Regulars, commanded by Brig. Gen. Romeyn Ayres, to support Burbank’s left. A third, belonging to Col Patrick O’Rorke, pushed straight up the turnpike. “We passed through many strange experiences as we advanced,” remembered one New Yorker. “One thing I noticed quickly. My heart was out of place, had jumped up into my throat and stayed there quite a while.”

For Jackson, a solution quickly emerged. Mahone’s resistance had fixed the Yankees in place. Now, if Jackson could get troops from his own column onto the Plank Road, they might wheel north and fall on Sykes’s right flank.

Jackson owed the possibility that lay before him to Joseph Hooker, for the Union advance that day was a discordant mixture of excessive speed and timidity. On Hooker’s left, Meade led the V Corps down River Road so far and fast as to leave Sykes’s division behind; when the fighting commenced on the turnpike, Meade (four miles to the northeast) could do nothing to help. Conversely, Slocum’s XII Corps stood still on the Orange Plank Road. That irascible, sometimes cautious officer stopped his advance at the first sight of Jackson’s Confederates — just over a mile into the maneuver. (It was likely his report back to Hooker that caused the Union army commander his first wavering of the day.) While Sykes’s men battled, Slocum stood about a mile to his right-rear. Sykes soon learned that he had outdistanced Slocum by just enough to leave the right flank of the Fifth Corps dangling dangerously.

As commanders on both sides struggled to understand the landscape and the intent of their opponents, fighting on the Orange Turnpike intensified. McLaws pushed forward Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s brigade of South Carolinians south of the turnpike and turned out two brigades to prevent any Yankee advance from the direction of River Road to the north. Soon, fighting raged on a front a half-mile long. Sykes sent word back to Hooker: enemy forces were “superior to my own.”

Jackson now seized the opportunity delivered him by Slocum’s aborted advance. He wheeled the division of Brig. Gen. Robert Rodes off the Orange Plank Road, plunging northward toward Sykes’s right flank. Just two Union regiments confronted Rodes’s men. They fought desperately, trying to gain time—“a desperate and exciting conflict,” a man from New York called it.

By then, Sykes sensed the danger, sensed the futility of fighting alone as the army’s vanguard. Hooker did, too. At the same time that Sykes decided to give up the right on the turnpike, Hooker decided to recall the entire Union advance — Meade on River Road and Slocum on the Plank Road, too (“I was hazarding too much,” Hooker later explained. “I had no alternative but to turn back.”). At midafternoon, Sykes began the delicate, often deadly process of extracting his command from battle. By 4:00 p.m. it was done. Hooker ordered his columns not back to the powerful ridge overlooking Mott’s Run, but instead to the lines around Chancellorsville they had left that morning — lines beset by low, swampy ground.

Hooker’s decision to withdraw that afternoon astonished his subordinates, prompting wails of disappointment rarely matched in the history of the army. He later suggested that fighting on the defensive had been his plan all along. If so, none of his subordinates knew that, and so the day’s events seemed nothing short of a catastrophic reversal. Hooker’s topographical engineer, Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, was closely involved in planning the campaign. “We went forward filled with high hope,” he told his fiancé, “but that steady purpose was wanting in the controlling power. We halted, we hesitated, wavered, retired.” He lamented, “I know we could have done it.”

To a man, the high command of the army stood in disbelief when “Fighting Joe” Hooker — the aggressor, the deprecator — opted not to fight. The moment demolished their confidence in the army commander.

No matter the tactical wisdom, no matter the expectations of his subordinates, Hooker’s decision did something more important than confuse or disappoint. It delivered the initiative to Robert E. Lee. Since September 14, 1862, on Maryland’s South Mountain, through Antietam and Fredericksburg, and all the way to Chancellorsville on the morning of May 1, 1863, the Union army and its commanders (though not often victorious) had repeatedly forced Lee to react to them. But in a span of a few hours on May 1, 1863, on the McGee, Lewis, and Leitch farms east of Chancellorsville, that changed. The combination of Confederate tactical success and Hooker’s caution delivered to Lee a power he relished, one he needed if he had any chance to win a war-changing victory. Lee would ride that tide of initiative — the ability to force the Union army to respond to him — through legendary days to come at Chancellorsville, all the way to a stone wall atop Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg, on July 3, 1863.

Related Battles

17,304

13,460