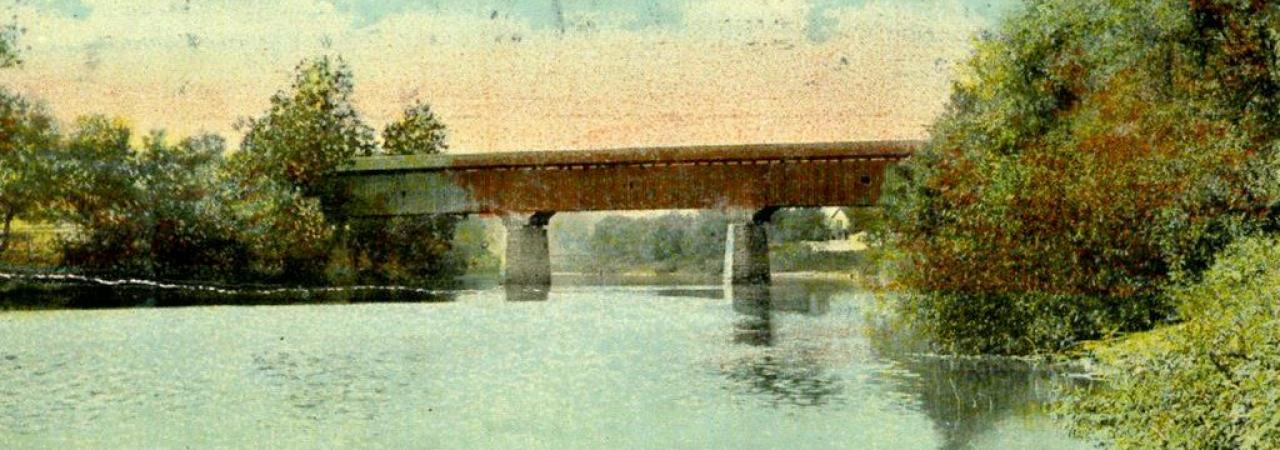

Old Bridge over Licking River, Cynthiana, Kentucky.

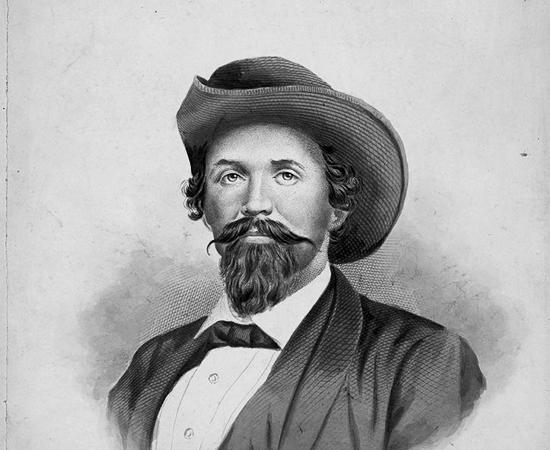

Thunderbolt, horse thief, raider – depending on which side of the Mason-Dixon Line one resides might determine which epithet one would use to describe John H. Morgan. One phrase that can be used with certainty during his Last Kentucky Raid of 1864 is "glory hound." Another would be insubordinate.

After the Great Raid of 1863, both Morgan and his command were shells of their former selves. Morgan’s men, 2,500 strong at the start of the raid across Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, were, for the most part, guests of the Union prison camp system - Morgan himself and many of his officers were incarcerated at the Ohio State Penitentiary. Morgan, along with a handful of others, escaped in November and returned to Confederate lines, and to his love, Mattie Ready, who he had married the previous December in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, a ceremony presided over by the Bishop General, Leonidas Polk. After the Great Raid, Morgan vowed to never be taken prisoner again as his love for his wife was all-consuming.

After making visits to Richmond, Virginia, and Joseph E. Johnston’s location in Georgia in an effort to secure the use of the veterans who escaped the disastrous Great Raid, Morgan was only able to obtain the release of a battalion. In the meantime, he had broadsides published announcing his intent to raise another force, welcoming all to his command.

In 1864, Morgan was assigned to southwestern Virginia, where he was to work with William “Grumble” Jones. However, as he did in 1863, Morgan defied orders and took his new command of nearly 3,000 men towards Pound Gap, crossing into Kentucky in early June 1864. This force, unlike the troopers who served him in 1862 and 1863, was a mix of undesirables, men who had not served with him before, and a small core of his old veterans. Missing was his right-hand man, Basil Duke, who brought not only tactics to Morgan’s raiders, but also the discipline necessary when operating in the enemy’s rear. Duke was still a prisoner and would not be exchanged until August 1864.

With three brigades, one on foot due to a lack of mounts, Morgan moved across eastern Kentucky, arriving at Mount Sterling on June 8th, capturing a Union depot after a brief engagement. But here, Morgan’s inability to be a disciplinarian came to the fore, as the local bank was robbed by men under his command. The bank held the funds of local, and mostly pro-southern, citizens. Moving towards Lexington, the raiders robbed banks in Winchester as well as Lexington, and in Lexington, his men would rid civilians of their valuables as they passed on the street. While in Lexington, Morgan was able to capture 1,100 horses, some that were for Federal service, but many others from the farms surrounding Lexington. One of Morgan's men wrote the following in his diary:

Genl. Morgan took his 2d. Brig., & went on to Lexington this evening to serve that city as Mt. Sterling had been served: bank robbed, stores plundered, universal pillage of private property! Am perfectly disgusted with Morganism. The whole programme seemed plundering, which the ‘old hands’ call ‘bumming.’ Evil only can come of such work.

Edward Guerrant

Moving towards Georgetown, the raiders attempted to rob yet another bank, but were stopped by one of the Confederate brigade commanders from the Georgetown community. On the afternoon of June 10th, Morgan moved his small division towards Cynthiana, going by an indirect route to throw off any Federal pursuers from his real destination. Morgan was familiar with Cynthiana, having had business dealings there pre-war, as well as participating in a State Guard encampment in 1860. Cynthiana had a road network that would allow Morgan to maneuver in a variety of directions, and the Kentucky Central Railroad, an important supply route for eastern Tennessee, passed through the heart of town and was a military target.

After an exhausting all-night ride from Georgetown, Morgan arrived three miles south of Cynthiana and split his command into two forces. One brigade would continue along the direct approach to town, while two brigades would swing towards the east and approach Cynthiana from that direction. This was a tactic that had served him well on his visit to Cynthiana in 1862.

Facing Morgan was a mix of 250 untrained one hundred days men from the 168th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and 100 local Home Guards. The 168th, like all one hundred days regiments, was not intended to see combat, instead, these regiments were supposed to serve at prison camps, guarding supply depots, as well as rear area railroad guard duty, freeing up other soldiers for the Union operations that would start in May. The 168th OVI had been dispatched from Ohio to get in front of Morgan while Stephen G. Burbridge, who had been tasked with a raid into southwestern Virginia but had turned to chase Morgan once he learned of the latter’s raid, would catch up and destroy Morgan’s division.

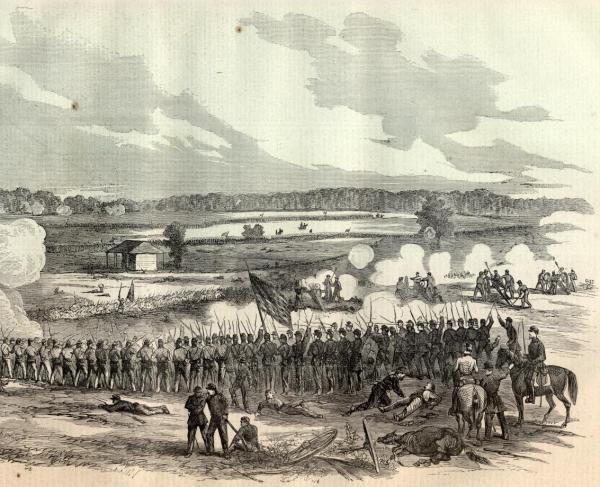

The 168th had arrived in Cynthiana a few days before and made camp on the south side of the South Fork of the Licking River. When Morgan’s men arrived in the early dawn hours of June 11th, a portion of the 168th was deployed on the south side of the river, defending behind a stone wall, but with the waist deep Licking to their immediate rear. The Home Guard and other portions of the 168th were deployed in various brick buildings on the north shore, as well as the two-story railroad depot. The Confederate brigade under command of H. Giltner moved quickly against the Buckeyes on the south shore, causing many to surrender and others to try to flee across the river, where some were shot in the back. The men who were able to flee joined their comrades on the north side of the river and shot at the Confederates as they moved across the covered bridge and headed towards the depot. In the meantime, the rebels that had been sent to the east now swung into town. The Federals held up in the depot building for some time, while others had taken a position in the three-story Rankin House, an excellent defensive position north of the depot and along the railroad.

In an effort to drive the Federals out of their defensive works, the Confederates started fires, most notably in a stable near the Rankin House. Morgan’s command had no artillery to shell the Federals from their positions and hoped that the heat and smoke from the fires would drive the Federals to capitulate. The fires raged out of control, and the heat and smoke did cause the remaining Union troops to surrender. The conflagration would cause the destruction of thirty-seven buildings in the heart of Cynthiana, a town noted for its southern leanings.

The town fighting lasted 60-90 minutes. In the meantime, arriving one mile north of town via trains were six hundred troops from the 171st Ohio (another one hundred days regiment), along with detachments of two Kentucky regiments. This force could not come to the aid of the forces in town as Keller’s Bridge had been burned a few days earlier by a detachment of Confederates (but after the 168th Ohio had arrived in town). Fleeing men from the town fight were moving north, and told the Federal commander, Edward Hobson, about the town fight and surrender. These same fleeing men were noticed by the Confederates, and Giltner’s brigade moved to intercept them, arriving from the west. There they bumped into Hobson’s force and fighting started between the Confederates and Federals across a railroad cut. Giltner’s men were low on ammunition, having fought at Mount Sterling and in the town fighting.

Our men pressed closely upon them & the battle raged fiercely. I have never seen such obstinate fighting. They were evidently two or three to our one in numbers, & handled by a gallant officer. We discovered by their volleying fire, which at times was terrible, & their steadiness under fire, & evolutions in face of an Enemy, that we were fighting trained troops. We might have been mistaken, but the evidence was overwhelming for the belief. No “100-day” men.

We fought & bled & prayed for Genl. Morgan to come to our help before we were out of ammunition & run over by our Enemy. Drops of blood almost oozed from the pores of the Col. & his officers. All were surprised & outraged by Genl. M’s. delay.

Edward Guerrant

Morgan had been busy paroling prisoners and had not been aware of Giltner’s encounter at Keller’s Bridge. Finally, Morgan brought the rest of the command, approaching Hobson’s force from the southeast. Hobson, in a bend of the Licking River, could not escape, but formed his forces to face all directions and was able to combat the Confederates for about four hours. Flags of truce were sent to the Federals, and after four to six hours of negotiations, the Federals surrendered. This delay would have serious consequences for Morgan’s command.

Morgan, due to the lateness of the day, decided to stay in Cynthiana for the evening. He received confirmation that Burbridge’s veterans were in pursuit, but decided to stay and make a fight of it. Giltner’s command, down to just a handful of rounds each, as ordered to use the Federal rifles captured from Hobson’s men, but as the vast majority of these were noted as inferior Giltner’s men refused. Morgan, through desertions and combat casualties, was at that point down to about 1500 men.

In the dawn hours of June 12th, Burbridge’s 2,000 men came to Cynthiana from the east, having gone from Lexington to Paris due to Morgan’s misdirection when moving to Cynthiana. Burbridge deployed two of his brigades on foot on either side of the Millersburg Pike and they moved against Giltner’s men, who had been deployed the night before on the high ground east of Cynthiana. A gap of a quarter mile or more existed between Giltner’s brigade and the other two Confederate brigades, both under the command of D. Howard Smith, which were facing the roads to the southeast of town. Burbridge’s men were initially rebuffed, so he moved two more brigades, one on either flank, in a mounted maneuver to outflank Giltner’s line. Smith tried to bring his forces to assist Giltner but was unable to connect his command due to one of Burbridge’s brigades that had slid in to fill the gap that existed between the Confederates. Pandemonium ensued on the Confederate side. Horse holders fled, leaving their comrades in a bind. Federals swarmed the rebels, scattering the defenders in a variety of directions. Morgan fled to the northeast and eventually made his way back to Virginia. Another small force made its way to Tennessee. Much like in 1863, Morgan had lost another small cavalry division and defied orders. “Grumble” Jones would be killed in battle at Piedmont on June 5th, and had Morgan not been moving his command towards Pound Gap, would have been in a position to support Jones.

Morgan would be killed on September 4th, 1864, at Greeneville, Tennessee. Ironically, he was not supposed to be there, having yet again defied orders. He was also under investigation for the criminal activities that had occurred in Kentucky.

Morgan’s destruction of his division in 1863, and his incessant need to raid in Kentucky caused him to ride for glory. However, not having his officers who were with him in 1863, and his lack of self-discipline and inability to instill discipline in his command, was in great evidence on the Last Kentucky Raid.