"Wheeling, Va. Donforth, Bald & Co. Philadelphia." 1850.

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, running westward from Baltimore to the Ohio River, commanded the attention of both armies during the Civil War. A crucial lifeline for Abraham Lincoln to move troops, supplies, and materiel of war, Union commanders dedicated thousands of troops to guard its many bridges, tunnels, and blockhouses, while the Confederates sought any opportunity to disrupt the rail line. In April and May of 1863, two Confederate generals attempted a concerted strike at the B&O that, if successful, would cripple the lines of Federal communication and transportation through the western sections of Maryland and Virginia.

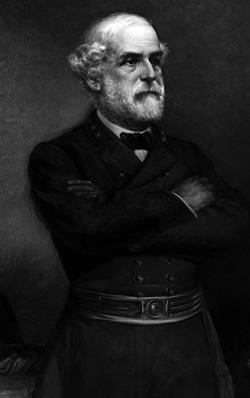

In March 1863, Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden proposed to Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee a two-pronged assault on an expansive swath of Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Originally the brainchild of Confederate partisan John H. McNeill, Imboden desired to expand on McNeill’s plan to sever the B&O at Rowlesburg, Virginia, where three vital bridges crossed the Cheat River. Running roughly 445 feet long and standing 54 feet above the ground, the Tray Run Viaduct near Rowlesburg was one of the most impressive engineering feats of the entire B&O line. Robert E. Lee had long recognized the importance of this section of the line, stating in 1861 that severing the B&O at Rowlesburg “would be worth to us an army.”

Imboden’s plan called for Brig. Gen. William E. “Grumble” Jones to take a northerly route towards Cumberland, New Creek, and Romney, before striking west towards Oakland and Rowlesburg. Simultaneously, Imboden would take a southerly route, clearing a Federal garrison at Beverly and reuniting with Jones at Weston or Buckhannon, before striking west to Grafton and Parkersburg. Along the way, the Confederate columns would destroy bridges, tunnels, viaducts, telegraph lines, and rail stock. Jones and Imboden could likewise use the foray to recruit their depleted ranks, capture horses, cattle, and supplies, and disrupt the statehood movement in the northwestern counties of Virginia, where elections were slated for May.

After carefully studying the plan, Lee proffered his approval on March 11, promising support from General Samuel Jones, commander of the Department of Western Virginia. Confederate president Jefferson Davis was likewise enthusiastic, believing “now is the time to destroy the Cheat River Bridge.” After more than a month of planning and posturing by the generals involved, and near-constant rain, Imboden set off from Shenandoah Mountain on April 20 with approximately 1,800 men. Supplemented the following day by additional troops under General Samuel Jones, Imboden’s column swelled to more than 3,300 men.

Also on April 21, Grumble Jones set off from Lacey Springs, Virginia with a command of 2,900 men. Initially, Imboden would face the more difficult challenge, navigating two mountain ranges and 70 miles over a span of four days in unforgiving snow, rain, and sleet. Swollen rivers hampered both commands, but on April 24 Imboden realized his first objective with the capture of Beverly, the seat of Randolph County. The Union garrison of some 900 men under the command of Colonel George R. Latham put up a forceful defense of the town for three hours before retreating to Buckhannon, eluding Imboden’s effort to capture the entire garrison.

After crossing the South Branch of the Potomac River, on April 25 Jones’s column ran into a federal garrison holding the Greenland Gap pass through New Creek Mountain. For five hours the command of 85 men held Jones in check from a log church turned makeshift fort, the Federal commander stating his troops “will fight to the last crust and cartridge.” The garrison capitulated only when the structure was set on fire, though Jones had lost precious time and dozens of casualties.

This was all too much for Brigadier General Benjamin Stone Roberts, only recently charged with overseeing the Federal garrisons in the northwestern counties. Roberts began recalling his available troops to consolidate at Clarksburg, complaining that recent rains had left the roads impassable for him to chase after Jones and Imboden. An exasperated General Henry Halleck fumed that “I do not understand how the roads there are impassable to you, when, by your own account, they are passable enough to the enemy.”

On April 26, Grumble Jones divided his command, sending a detachment north towards Oakland, Maryland, while Jones led the remainder west toward his objective at Rowlesburg. Oakland quickly fell, and the raiders destroyed the B&O bridge over the Little Youghiogheny River. From there the detachment moved west towards Cranberry Summit and Kingwood, further damaging the railroad and telegraph as they went. Jones continued on, arriving at Rowlesburg later that day. Defending the vital rail station was Maj. John H. Showalter and a command of 250 men of the 6th West Virginia Infantry.

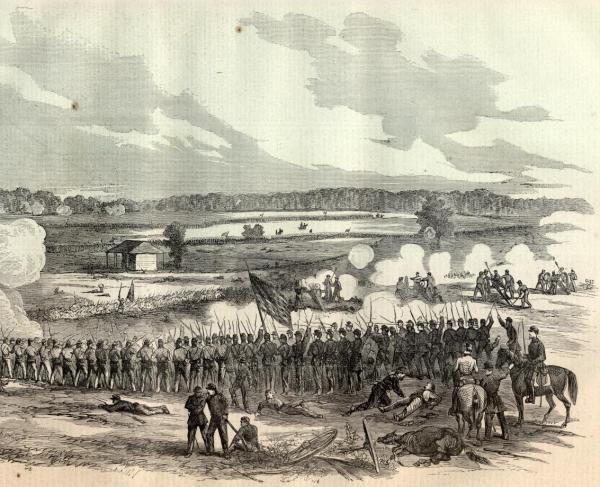

Jones divined a two-pronged assault from the south and east. Showalter’s command put up a spirited defense with advantageously placed artillery and barricaded defiles, such that by nightfall Jones broke off the attack and bypassed Rowlesburg, leaving the bridges intact. Unknown to Jones, Showalter also abandoned Rowlesburg, fearing that Jones would cut his avenue of retreat. The bridges and viaducts at Rowlesburg were not seriously threatened for the remainder of the war.

After destroying a suspension bridge near Kingwood, Jones reunited his force and captured Morgantown, today home to West Virginia University, even sending riders into the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania to gather horseflesh. Imboden continued his advance, capturing Buckhannon on April 29, while Jones turned south towards Fairmont, another vital B&O depot. After a brisk skirmish at Fairmont where Jones captured more than 200 prisoners, he achieved one of the more significant accomplishments of the raid in the destruction of the B&O bridge over the Monongahela River. At a cost of more than $400,000.00, the imposing three-span, 615-foot iron bridge at Fairmont had been the costliest structure on the B&O line. Before leaving Fairmont, Jones’s men also visited the home of Francis Pierpont, Governor of the Restored Government of Virginia, and burned his personal library.

Jones continued south and linked with Imboden’s command at Buckhannon on May 2, though not for long. Opting to forego an attack on a more formidable Federal garrison at Clarksburg, the columns again split. Imboden would shepherd south to Summersville the immense quantity of livestock and wagons captured thus far and await Jones, who would strike west along the Northwestern Virginia Railroad. Following the Staunton & Parkersburg Turnpike, Jones was selective in his targets, capturing some Federal garrisons and bypassing others. Late on May 9, his column resurfaced at Burning Springs in Wirt County.

Oil had been discovered at Burning Springs in the 1830s, and by the Civil War nearly 100 wells were producing some 250 barrels a day. Jones fired the open wells, pumphouses, and some 20,000 barrels of oil, the ignited oil flowing into the nearby Little Kanawha River. The destruction created “great pillars of flame, resembling pyramids of fire…lighting the surrounding country for miles.” It would be two years before Burning Springs resumed production.

Jones turned his column south and rejoined Imboden’s command at Summersville on May 14. Their columns soon recrossed the Allegheny Mountains and returned to the Shenandoah Valley, bringing the Jones-Imboden Raid to a close. General Benjamin Stone Roberts, after offering only tepid resistance as the Confederate columns cut a swath across northwestern Virginia, was quickly replaced by Brigadier General William W. Averell.

In approximately one month the columns under Jones and Imboden covered a combined 1,100 miles. The Confederates captured more than 4,000 head of cattle, up to 2,000 horses, and around 1,000 small arms. While one of the major objectives at Rowlesburg was not realized, destruction along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was significant. The raid resulted in the damage or destruction of 26 bridges, one tunnel, two locomotives, and miles of track and telegraph lines. Even so, after two years of war, the B&O company had the foresight to move to safety much of the rolling stock and repair material, helping to speed repairs and reopen the railroad to traffic after only ten days. Confederate losses were light, losing less than 90 men while inflicting more than 800 casualties on the disparate Federal forces, and capturing the attention of up to 25,000 Union troops sent to dispatch them. Some 400 – 500 recruits were added to the Confederate ranks.

Less than a month later, on June 20, 1863, West Virginia was formally admitted as the 35th state. Federal garrisons were strengthened across the state, such that no future Confederate incursions would realize the scope and breadth that the Jones – Imboden Raid achieved. While the raid was void of any major battles and has been overlooked in favor of other events happening simultaneously, Confederate soldiers would long remember their involvement. Recalling the destruction of the oil wells at Burning Springs, one Confederate veteran noted in 1906 that, even after more than 40 years, “the soldiers who were with General Jones, at this day, get excited when that fire is mentioned…”

Further Reading: