The Long Road Back to Kentucky

At the outbreak of the Civil War it appeared as though Kentucky would be the critical battleground of the trans-Allegheny west. When Tennessee seceded after President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops to “suppress the rebellion,” Kentucky, lying directly along Tennessee’s northern border and controlling access to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, now played a pivotal role. In May 1861, Kentucky’s governor, Beriah Magoffin, proclaimed neutrality which further complicated the matter.

Both Union and Confederate forces breached Kentucky’s neutrality in the summer of 1861. The raising of a pro-Union Home Guard by legislative edict in May and the bold recruiting and training of Union troops at Camp Dick Robinson in Garrard County in August were obvious violations. Congressional and legislative elections in Kentucky that summer revealed overwhelming pro-Union victories; the pretense of neutrality all but evaporated in the face of strong pro-Union sentiment in the Commonwealth.

In response, the seceded states rattled the sabre when Confederate troops, commanded by Major General Leonidas Polk, moved from west Tennessee to Columbus, Kentucky, the railhead of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad (M&O) on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River, in early September. That move was immediately countered by the shifting of Union troops from Cairo, Illinois to the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers at Paducah and Smithland, Kentucky, respectively, by Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant.

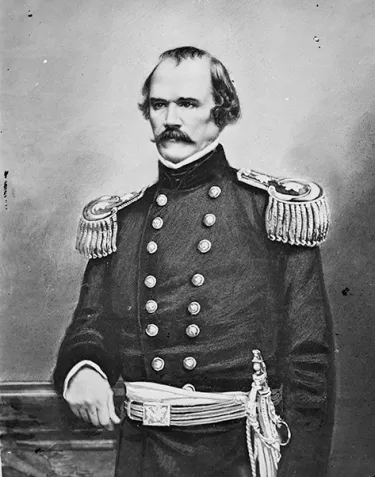

With the appointment of Kentucky native General Albert Sidney Johnston as commander of all of what was known as Department Number 2 – that included Kentucky – a Confederate northern defense line was established in the trans-Allegheny west that extended from Columbus to Bowling Green, Kentucky, and all the way to Cumberland Gap. Because of Kentucky’s initial claims of neutrality, Tennessee had constructed Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River in the summer of 1861 to defend its northern border. Another fort had been constructed at Island Number 10 on the Mississippi River. Those forts quickly became garrisoned installations in Johnston’s vast defense line.

The Confederate defense line was destined to collapse; it was too long – more than four hundred miles – and it was broken by two great, navigable rivers that ran south to north through western Kentucky. The beginning of the end occurred when a small Confederate force protecting east Tennessee moved into Kentucky, crossed the Cumberland River, and was struck by Union forces – most of whom had been trained at Camp Dick Robinson – near a village named Logan’s Crossroads on January 19, 1862. In the fog and sleet, Confederate Brigadier General Felix Zollicoffer was killed and his force crushed. The victorious Union forces, commanded by Brigadier General George H. Thomas, had broken the eastern flank of Johnston’s defense line and were in a position to threaten his rear.

On February 6, Grant’s forces, moving up the Tennessee River from Paducah accompanied by newly completed naval gunboats, forced the surrender of Fort Henry; less than two weeks later Fort Donelson fell to Grant’s combined naval and land forces. Johnston had fallen back to Nashville, Tenn. The defense line in Kentucky had been shattered. Johnston’s only recourse was to withdraw to a position below the great bend of the Tennessee River so that the widely separated elements of his army could coalesce. Johnston chose Corinth, Mississippi, the site where the Memphis and Charleston Railroad (M&C) crossed the M&O. There his army was augmented by reinforcements from Memphis, Tenn. and Pensacola, Fla. But Grant followed relentlessly, moving his Union forces up the Tennessee River to Savannah and Pittsburg Landing in southwestern Tennessee.

Then, on April 6, Johnston surprised Grant by striking his unwary divisions near Shiloh Church. All four Confederate corps drove Grant’s army back to the Tennessee River in ferocious assaults, but Johnston was killed in the action, and the Confederate drive faltered in the late afternoon. On the second day, Grant counterattacked after being reinforced by elements of Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio that had marched to Grant’s assistance from Nashville and had arrived on the night of April 6. The Confederates, then commanded by General P.G.T. Beauregard, were hurled back. The two days of fighting at Shiloh saw the largest bloodletting ever witnessed on the North American continent up to that date; there were more than 23,000 combined casualties.

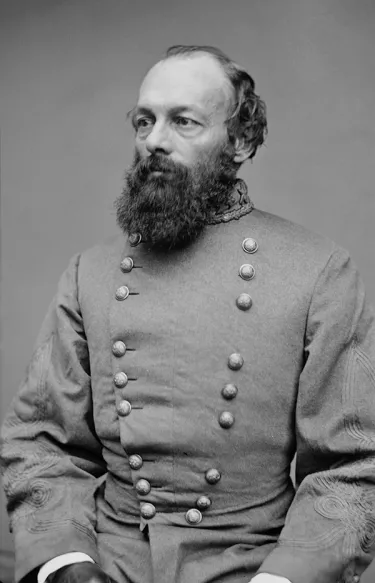

The Confederate army withdrew to Corinth and again to Tupelo, Miss. on the M&O. Beauregard soon asked to be relieved of command due to ill health, and in his place as commander of Department Number 2 was named General Braxton Bragg, one of the army’s hard-fighting corps commanders.

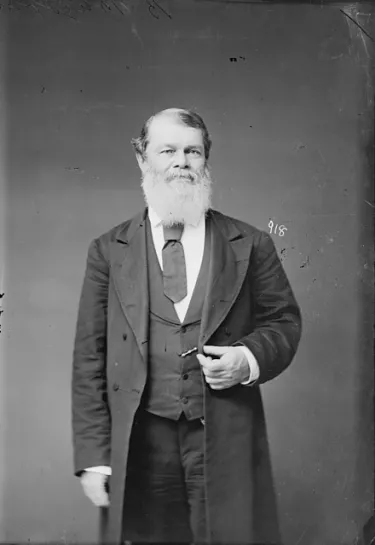

Bragg would become a most unpopular commander of the force that was by then being referred to as the Army of the Mississippi. He had already displayed impatience with subordinates and a mercurial temperament; he was difficult to approach, prone to migraine headaches, and he quickly made enemies among those upon whom he had to rely. Altogether, though, Bragg was a capable commander, and his plans to retake central Tennessee and, possibly, Kentucky – and the execution of those plans – revealed a high level of competence.

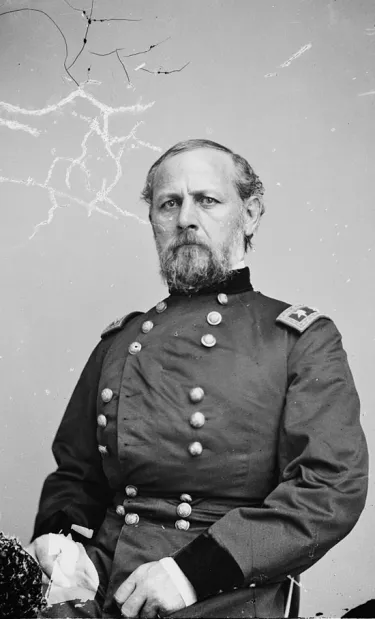

Observing a division of Buell’s army, commanded by Major General Ormsby M. Mitchel, moving east from Corinth toward Chattanooga, Tenn. alongside the M&C, Bragg believed he must respond quickly. Chattanooga could not fall into Union hands; it was a critical rail and communication center, connecting the trans-Allegheny west with Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, by rail and telegraph lines. A smaller Confederate army, known as the Department of East Tennessee and commanded by Major General Edmund Kirby Smith, near Knoxville and protecting the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad (ET&V), was in a position to assist Bragg.

Bragg determined to move. After sending Major General John P. McCown’s division along the M&O to Mobile, Ala. and then along rail lines to Montgomery, Ala.; Atlanta, Ga.; and Chattanooga to reinforce Smith, Bragg noted that the division reached its destination in less than ten days. Leaving a sufficient force at Tupelo, he then ordered his cavalry and artillery, along with his quartermaster, subsistence, ordnance, ambulance and baggage trains, to move overland through northern Alabama to Chattanooga, while he sent his infantry – nearly 30,000 strong – by rail from Tupelo to Mobile and then to Montgomery and Atlanta and finally to Chattanooga, beating Mitchel’s slow-moving division to that critical city. It was the longest and largest movement of troops by rail in military history up to that date.

On August 1, Bragg conferred with Smith in Chattanooga. Smith agreed to place his command at Bragg’s disposal, but suggested that his army threaten the enemy’s force at Cumberland Gap. Smith additionally requested more reinforcements, and Bragg sent him the brigades of Brigadier General Patrick R. Cleburne and Colonel Preston Smith. Many of Kirby Smith’s troops hailed from the trans-Mississippi and they had already campaigned for more than 1,000 miles.

Fourteen days later, Smith moved his army, some 16,000 strong, out of Knoxville, Tenn. through Rogers Gap, arriving at Barbourville, Kentucky on August 18. General McCown was sent to Knoxville to take command of the forces left there protecting the ET&V. Leaving one division – Brigadier General Carter L. Stevenson’s – south of Barbourville to guard his rear against Major General George W. Morgan’s Union forces at Cumberland Gap and to keep open his line of communication and support to Chattanooga, Smith moved north toward the rich bluegrass region of Kentucky. In three days his army moved ninety miles in soaring heat through the drought-stricken mountains. Bearded, rough, shoeless, ill-clad, and ravenously hungry, no rougher or more fearsome-looking soldiers ever campaigned in the Commonwealth than those in Smith’s newly-dubbed Army of Kentucky.

Through Pound Gap, Major General Humphrey Marshall directed his Department of Southwest Virginia into the mountains of Kentucky in an effort to protect Smith’s flank and long line of support and communication.

On August 29, 30, and 31, Smith’s forces battled a hastily-formed Union army of mostly raw recruits, numbering just under 8,000 men, commanded by Major General William “Bull” Nelson, along the Old Wilderness Road south of Richmond, Kentucky, virtually annihilating it on the last day. Smith captured more than 6,000 of the enemy and all of their ordnance, wagon trains, stores and supplies. Two days later, Smith’s army entered Lexington, the heart of the Bluegrass. His forces quickly fanned out from Lexington, seizing Frankfort, the state capital, the Lexington and Frankfort Railroad, and Paris and Cynthiana on the Kentucky Central Railroad; elements went as far north as Covington, just below Cincinnati, Ohio.

In Lexington and the surrounding towns and countryside Smith’s troops purchased, impressed, and confiscated all the quartermaster and subsistence stores available. The Confederates seized all supplies of the Union occupation forces that they had not burned upon their evacuation of the city. Every store, shop, and farmyard was opened up and cleaned out of all of the clothing, shoes, hats, meats, grains, meal, feed, harness, weapons, forges, sheet and bar iron, and other necessities. Thousands of cattle, sheep, hogs, horses and mules were seized. Wagon trains transported the stores from Lexington to Nicholasville and on to Hoskins Crossroads, formerly the site of Camp Dick Robinson and the designated supply base for the Confederate invasion. Camp Dick Robinson was south of the Kentucky River gorge and only fifteen miles from the western stem of the old Wilderness Road, Smith’s line of supply and communication.

Bragg began to move northward from Chattanooga on August 28. With a feint toward Nashville, Bragg, on September 7, moved toward Glasgow, Kentucky from Carthage, Tennessee. He had determined to enter Kentucky; there were prospects of large numbers of Southern sympathizers in the Commonwealth rising up to support the Confederate invasion, but, moreover, Kentucky was fertile ground for foraging. To accomplish both tasks, Bragg brought with his Army of the Mississippi – 28,000 strong – vast wagon trains, some loaded with weapons to be distributed to new recruits, others empty and to be filled with seized and impressed stores. So long were Bragg’s quartermaster and subsistence trains that it took them nearly three days to pass any given location along the Nashville and Bardstown Turnpike.

Buell responded to Bragg’s movement. After he was certain Bragg was heading into Kentucky, Buell moved his Army of the Ohio from near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, toward Bowling Green, Kentucky, in an effort to keep the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) to Nashville open as his means of supply even after Confederate Colonel John Hunt Morgan and his cavalry brigade had destroyed the railroad’s tunnel at Gallatin, Tennessee. Buell reached Bowling Green on September 13. That same day Bragg reached Glasgow on a spur line of the L&N where he scoured the countryside for subsistence stores.

Bragg moved ahead; for the first time the Army of the Mississippi was operating with no base of supply or line of support and communication (as Buell’s army was now operating on Bragg’s rear). Bragg’s army would have to live off the land. Only the long, tenuous line to the rear of Smith’s army – the Wilderness Road to Cumberland Gap and the roads to Knoxville and Chattanooga – would provide the two armies with any means of support and communication with their civil government.

After a bloody attack against the Union defenders of the enormous Green River Bridge of the L&N at Munfordville, Bragg forced the surrender of the Union garrison there of over 4,000 men on September 17, thereby seizing sizeable numbers of horses, mules, ordnance, and military stores. The Confederates torched the Green River Bridge. The twin victories at Richmond and Munfordville were widely heralded by the Confederate government and Southern citizenry; coupled with the victory by Robert E. Lee’s army at Manassas on August 31, the prospects for a successful conclusion of the war by the Confederacy seemed bright.

Claiming his army was not in a position to turn around and confront Buell’s army at Munfordville due to shortages of subsistence stores, sickness, and the weakened state of his men – complaints which then were probably very accurate – Bragg moved toward Bardstown in an effort to rest his army before joining forces with Smith’s army in central Kentucky. His men had already campaigned more than 1,000 miles since July. Bragg had had no opportunity thus far for meaningful foraging, and the joining of his command with Smith’s would not only increase the number of combatants in Kentucky, it would provide to the Army of the Mississippi time to forage for subsistence and to obtain the rich stores already seized by Smith’s forces. It would also put Bragg onto the only open line of support and communication to Chattanooga and his government. With Bragg’s army out of the way, though, Buell moved directly toward Louisville astride the L&N. The Army of the Ohio reached the River City on September 25.

Bragg quickly discovered that the sons of Kentucky were not rallying to his cause. A proclamation issued at Bardstown to the citizens of the Commonwealth tried to lure recruits by declaring the Confederate army’s intention to free the people and the state from the tyrant’s yoke. It did not have the desired effect, however. Few Kentuckians joined the ragged Confederate armies. “Unless a change occurs soon,” Bragg wrote, “we must abandon the garden spot of Kentucky to its cupidity. The love of ease and fear of pecuniary loss are the fruitful sources of this evil.”

Believing that if he could install a Confederate government in Kentucky he could conscript Kentuckians into his ranks, Bragg attempted to implement such a plan. He and Smith agreed to meet in Frankfort to swear-in as governor Bourbon County, Kentucky native Richard Hawes, who had succeeded Scott County native George Washington Johnson as governor of what had been the exiled Confederate government of Kentucky. Governor Johnson had died at Shiloh as a result of battle wounds. Hawes had actually been serving with General Humphrey Marshall ever since the evacuation of Kentucky.

Meanwhile, Buell’s army had been augmented by newly raised regiments from Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois that had poured in to Louisville as well as General Thomas’s division that had been on the march from Nashville. By September 30, Buell’s Army of the Ohio was nearly 55,000 strong, and he marched it out of Louisville to confront Bragg.

Buell tried to deceive Bragg about the movements of his vast Union force at the inception of his campaign. He sent Brigadier General Joshua W. Sill’s division of Major General Alexander McDowell McCook’s corps from Louisville, through Shelbyville, toward Frankfort, while an independent division under Brigadier General Ebenezer Dumont followed Sill. With his other commands, Buell moved toward Bragg’s army at Bardstown on three different routes. McCook’s Corps marched through Taylorsville, Bloomfield, and Mackville, skirting Bardstown on the north. Major General Thomas L. Crittenden’s corps marched through Mount Washington, Bardstown, and Lebanon, bypassing Bragg’s army to the south, and seizing the railhead of the L&N spur line at Lebanon to open a line of supply to Buell’s army from Louisville. Major General Charles C. Gilbert’s corps moved through Shepherdsville, Bardstown, and Springfield, directly pursuing Bragg.

With only limited, meaningful intelligence about the enemy’s movements, Bragg became uncertain as to the direction of Buell’s main thrust. He rode to Frankfort to meet Smith and inaugurate “Governor” Hawes on October 4, only to have the ceremonies cut short by the arrival of Sill’s and Dumont’s Union divisions outside of the capital city. On the firm recommendation of his two wing commanders, General Polk and Major General William J. Hardee, Bragg agreed that the army should withdraw from Bardstown toward Harrodsburg in the face of Buell’s advance. There it could form a junction with Smith’s army and protect the growing supply base at Camp Dick Robinson. No sooner had the army reached Perryville than Bragg ordered one full division – that of Brigadier General Jones M. Withers – detached and sent toward Frankfort, as Bragg continued to receive intelligence that led him to believe that the main thrust of Buell’s effort was in that direction.

Buell’s main effort was actually directed at Bragg’s force withdrawing from Bardstown. With the detachment of Withers’s division, Bragg’s army, considerably smaller than Buell’s even when fully intact, was reduced to less than one-half the size of its opponent’s.

The rear guard of Bragg’s main force skirmished with the leading elements of Buell’s advancing army – Gilbert’s Corps – all the way from Bardstown to Springfield and from Springfield to the outskirts of Perryville. By October 7, General Hardee reported that the skirmishing had become so intense that it was necessary to collect all of the Army of the Mississippi at Perryville and offer battle. What constituted Polk’s wing after the detachment of Withers’s division – Major General Benjamin F. Cheatham’s division – was then near Harrodsburg, followed by Brigadier General J. Patton Anderson’s Division of Hardee’s wing. Bragg and his staff rode more than thirty dusty miles from Lexington to Harrodsburg, and, at Harrodsburg, Bragg ordered Polk and Anderson to return to Perryville, having received Hardee’s urgent message. Bragg still was led to believe that the main thrust of Buell’s movements was directed toward Frankfort and, possibly, Lexington. The decisive battle, he surmised, would likely occur near Versailles.

Of overarching concern to Bragg were the enormous quartermaster and subsistence wagon trains and accompanying livestock collected by, principally, Smith’s army. A large number of those wagons were at or on the way to Camp Dick Robinson in Bragg’s rear. Smith had already ordered General Stevenson’s Division to march to Camp Dick Robinson to protect the wagon trains after General Morgan’s Union force evacuated Cumberland Gap. Stevenson had arrived there by the first of October. Smith’s wagon trains were still being forwarded to Camp Dick Robinson by October 7, and the roads from Lexington to Nicholasville and to Camp Dick Robinson and the roads from Versailles to Nicholasville were jammed with them. General Marshall’s forces had moved from Mt. Sterling to Lexington and Versailles in an effort to protect the movement of the wagon trains and bolster the Confederate defenses in the area. The extensive wagon trains, altogether more than fifty miles in length, needed protection. Whether he held Kentucky or not, Bragg could not leave the Commonwealth without the extensive stores and livestock collected there. Thus, to protect them – and to avoid a disaster on a battlefield that could endanger those wagon trains – was fundamental to the existence of the two Confederate armies, and Bragg’s primary concern.

Bragg continued to understand from all his intelligence that Buell’s movement toward Perryville from Springfield was not the main effort of the enemy. In that rolling countryside of central Kentucky, drained by deep gorges of rivers and streams, it was virtually impossible to obtain reliable information about the movements of the enemy. A close examination of the country through which the two armies campaigned confirms the problem. Given what Bragg believed to be the enemy’s size near Perryville – one of Buell’s three corps – and its nearness to the Confederate supply base at Camp Dick Robinson, Bragg intended to strike and destroy that force on October 8. Once the enemy was beaten, Bragg resolved to quickly move all of his forces to join Smith. Bragg’s wing commanders, Generals Polk and Hardee, though, believed that at least two Union corps were closing in on them. They were correct, although they were not privy to all of the intelligence Bragg was receiving of Buell’s thrusts toward Frankfort and Lexington.

Moving Cheatham’s Division off of the road to Harrodsburg from Perryville and along the dry bed of the Chaplin River to the bluffs at Walker’s Bend behind Colonel John A. Wharton’s cavalry, Bragg planned a surprise strike against what he believed to be the enemy’s left flank about three miles west of Perryville. The divisions of Brigadier General J. Patton Anderson and Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner of Hardee’s wing, positioned along high ground on either side of the Mackville Pike, could then continue the attacks to Cheatham’s left and roll up the enemy force.

What Bragg did not know, of course, was that he was about to engage elements of McCook’s Corps arriving from Mackville and that Gilbert’s Corps (whose presence was well known to Bragg, Hardee and Polk) on the Springfield Pike was in position to support McCook. Those two corps represented almost two-thirds of Buell’s army. Crittenden’s Corps was marching toward Perryville from Lebanon.

October 8, as almost all of the previous days of the Kentucky campaign had been, was intensely hot – nearing one hundred degrees – and the countryside was parched due to the persistent drought, leaving river and creek beds dry and the roads ankle deep in dust. The men and animals suffered terribly as fresh water was not to be found, and the lack of subsistence and forage weakened them and swelled the ranks of the sick.

After a spirited artillery duel, Bragg’s hard-fighting veterans attacked up long slopes and steep ridges against what they believed was the Union left at about 2 o’clock in the afternoon. In fact, they struck Brigadier General William R. Terrill’s brigade of Brigadier General James S. Jackson’s division of McCook’s Corps, and, as the attack progressed, two other brigades appeared on the ridgelines: Colonel John C. Starkweather’s of Brigadier General Lovell H. Rousseau’s division of McCook’s Corps and Colonel George P. Webster’s. It became a bloody melee. To Cheatham’s left, Buckner’s and Anderson’s Division joined the fray, only to run into more Union brigades: Brigadier General William Lytle’s and Colonel Leonard Harris’s of Rousseau’s Division. Wrote one Tennessee soldier: “It was a life to life and death to death grapple. The sun was poised above us, a great red ball sinking slowly in the west, yet the scene of battle and carnage continued. I cannot describe it.” To him Perryville was a “grand havoc of battle.”

The Union lines were hurled back. Union Generals Jackson and Terrill and Colonel Webster were killed and their ranks were decimated. Cheatham’s, Anderson’s, and Buckner’s divisions were shredded, yet pressed on, pushing the Union lines back more than a mile on the left flank and up the Mackville Pike. In the darkness, elements of Gilbert’s Corps – namely Brigadier General James B. Steedman’s brigade of Brigadier General Albin Schoepf’s division and Colonel Michael Gooding’s brigade of Brigadier General Robert B. Mitchell’s division and elements of other brigades – were sent into the fighting at the crossroads of the Mackville Pike and the Benton Road. Incredibly, however, most of Gilbert’s Corps remained stationary while the desperate and sanguinary battle played out in plain view of its men.

Nighttime finally brought a halt to the bloodletting. It had been a nightmarish afternoon for both sides. Of the 22,000 Union soldiers who were actually engaged that afternoon, 4,241 were killed, wounded, or missing. Bragg’s army lost 3,396 of its mere 16,000 men engaged. All those losses occurred in four to six hours of fighting.

That night Bragg realized that he was facing Buell’s whole army. Colonel Joseph Wheeler, whose cavalry brigade was patrolling the road from Perryville to Lebanon, reported the approach of Crittenden’s Corps. Already Bragg knew from the fighting that day that he had been contending with McCook’s and Gilbert’s Corps as Union wounded and prisoners-of-war had revealed. Although his army had tasted a tactical victory, Bragg withdrew it from Perryville that night; he retreated to Harrodsburg, closer to his supply base.

Buell moved slowly the next day; elements of his army marched toward Danville and Harrodsburg. At Harrodsburg, Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi finally joined Smith’s Army of Kentucky. The two armies withdrew across the Dix River to Camp Dick Robinson. From there, on October 12, Bragg and Smith began their retreat from Kentucky. Utilizing parallel roads to and beyond the Rockcastle River in order to divide and thus shorten the immense wagon trains, Bragg’s and Smith’s forces marched to London and Barbourville, finally moving through Cumberland Gap. With the army were quartermaster and subsistence wagon trains that were more than fifty miles long, hauling all sorts of clothing, boots, shoes, meats, grains, harness, leather goods, weapons, forges, steel, and countless other items, along with tens of thousands of cattle, sheep, hogs, horses and mules.

Bragg would be bitterly criticized for the invasion; there would be acrimony directed toward him by his chief lieutenants for his criticism of their actions between Bardstown and Perryville. Those relationships would deteriorate more and more with time. Buell would not only be criticized, he would be removed as commander on October 30. Major General William S. Rosecrans would replace him, and the Union army would become known as the Army of the Cumberland. Although Bragg acknowledged the failures of the campaign, to his credit he obtained for the army one of its richest harvests of the war. His seemingly endless wagon trains brought out of Kentucky enough fresh meat to keep his army in the field for the foreseeable future. He obtained enough clothing, shoes and boots to supply many of those in dire need, and he obtained enough horses and mules to replace many that had been rendered unserviceable or were worn out. To augment what was recovered in Kentucky, Bragg secured from the “redeemed” central Tennessee large amounts of horses and mules, wagons, subsistence stores, ordnance and quartermaster stores. Altogether, the invasion of Kentucky and the consequent redeeming of central Tennessee helped extend the war in the trans-Allegheny west. The newly-named Army of Tennessee would fight on for two and one-half more dreadful years; Braxton Bragg would remain its commander for just under half of that time.