History has not been kind to Charles Lee, the man whom George Washington referred to as “The first officer in Military knowledge and experience we have in the whole army….” He was a conundrum of a man—brilliant, but eccentric and erratic. His military career was filled with a plethora of peaks and valleys, and in the end, his own worst enemy was his ego.

Lee’s role during the Battle of Monmouth Court House in present-day Manalapan and Freehold, New Jersey, has been shrouded in controversy and myth. The popular idea of Lee being cussed out by Washington and relieved of command on the field in front of his peers has been misconstrued for several centuries, mainly because the repeated accounts of what happened that day have been from the memories of men who did not even witness the events they described. Lee’s performance at Monmouth was cautious, sloppy, courageous, and commendable, all at the same time. In the wake of the battle, only his personal honor had been injured—his reputation was already suspect to many of the officers in Washington’s circle—and because of this, Lee felt the need to have his name cleared of any supposed wrong-doings. He did not know when to back down and remain quiet. A court-martial would follow, and Lee’s career in the Revolutionary War came to an inglorious end. Over two-hundred and forty years removed from the events of June 28, 1778, Lee’s performance must continuously be reassessed, or it will be forever tainted by bias and myth.

After being held in captivity for nearly sixteen months, Lee returned to the Continental Army in May 1778, when he reassumed the rank of second in command. As Washington prepared to pursue Sir Henry Clinton’s British force across New Jersey, which was in retreat from Philadelphia toward the safety of New York City, Lee was not confident in the Americans. His absence from the army had made him ignorant of the transformation that the Continental soldier had undergone since December 1776 when he was captured by British dragoons in Basking Ridge, New Jersey. He still did not think that they were capable of standing toe-to-toe with British regulars on the field of battle. He could not have been more wrong. Combat experience and professional training at the hands of Baron von Steuben at Valley Forge had turned the Continental Army into a force to be reckoned with. Regardless, Lee assumed command of the army’s right-wing and led the advance into New Jersey on June 20, 1778.

Throughout the campaign, Lee lobbied for Washington to avoid an open engagement with Clinton. Instead, he argued that the British should be allowed to return to New York City and that the Americans should bide their time and wait for France to become more militarily involved—he understood, correctly, that France’s entrance into the conflict would ultimately decide its outcome. Washington, and some of his most trusted subordinates like Lafayette, Green, and Wayne, did not intend to let Clinton’s army escape New Jersey without a fight. By June 27, Lee and 4,500 men of his advanced corps, or vanguard, were encamped around Englishtown, some six miles away from the British at Monmouth Court House. Washington, who was leading the main body of the army several miles behind at Manalapan Bridge, rode ahead to meet with Lee that evening. No direct order to engage the enemy was apparently delivered by the commander in chief. Lee was to advance toward Monmouth Court House the following morning with his vanguard, keeping within striking distance of the enemy should they attempt to resume their march. Brigadier Generals Charles Scott and Anthony Wayne, who was serving under Lee, believed that Washington did intend them to attack, but Lee did not.

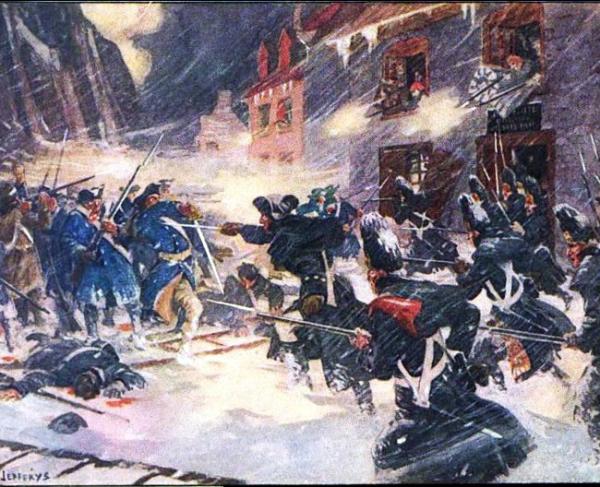

The next morning, June 28, his force advanced. The movement was cautious and slow because Lee did not have enough intelligence regarding the enemy’s position and the lay of the land. Eventually, though, contact was made between the two forces and the Americans formed up a line of battle just west of the village. The battle that Washington had been yearning for was at hand, and it was Lee’s job, in his mind at least, to keep the rearguard of Clinton’s army pinned down long enough for him to arrive with the main body and deliver the crushing blow. Things collapsed very quickly for Lee’s force. Clinton turned around General Charles Cornwallis’s division and moved it in the Americans’ direction. Without any orders from Lee, Gen. Scott, near the left-center of the line, began pulling his men back. This movement initiated a general retreat, and with the British now in pursuit, Lee’s vanguard was fleeing west. A potential disaster was in the works. Lee attempted to gain control of the confused situation, not quite sure himself of what had transpired. Luckily, for the Americans, the commander in chief was on the field.

George Washington had arrived in Englishtown roughly an hour and a half ahead of the Continental Army’s main body and sat down for breakfast sometime around ten in the morning, June 28, 1778. Six miles away, Major General Charles Lee’s vanguard of roughly 5000 men was just about to throw itself at the British rearguard north of Monmouth Court House.

Washington had ridden ahead of the main body toward the sounds of musket fire in the distance. Arriving in the fields west of the village, he expected to find Lee engaged with the enemy and pinning him in place. The situation was much different and he was greeted by retreating men along the road from Englishtown, quickly learning that Lee’s force was falling back in the face of the enemy. Washington continued on toward Perrine Ridge, a gently sloping rise north of the road and several miles west of the village. There, he attempted to rally some of the troops nearby and form them up in a defensive line. He then rode forward to find Gen. Lee. “Here, fortunately for the honour of the army, and the welfare of America,” Washington’s aide John Laurens remembered, “General Washington met the troops retreating in disorder, and without any plan to make an opposition.”

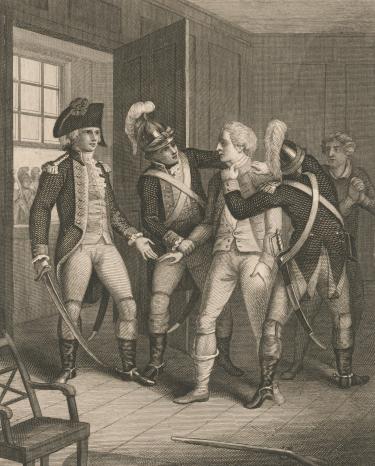

Lee was situated further east and south of the road on a hill near the Rhea farm when Washington found him. The exchange that occurred between the two commanders has fallen victim to myth over the centuries. Many widely accepted versions of the encounter have come from individuals who either recollected it decades later or were not even present at the time. Charles Lee, who obviously was there, remembered it as follows:

When I arrived first in his [Washington’s] presence, conscious of having done nothing that could draw on the least censure, but rather flattering myself with his congratulation and applause, I confess I was disconcerted, astonished and confounded by the words and manner in which his Excellency accosted me…. The terms, I think, were these—“I desire to know, sir, what is the reason—whence arises this disorder and confusion?” The manner in which he expressed them was much stronger and more severe than the expressions themselves. When I recovered myself sufficiently, I answered, that I saw or knew of no confusion but what naturally arose from disobedience of orders, contradictory intelligence, and the impertinence and presumption of individuals, who were vested with no authority, intruding themselves in matters above them and out of their sphere. That the retreat … was contrary to my intentions, contrary to my orders, and contrary to my wishes…. To which he replied, “All may be very true, sir, but you ought not to have undertaken it unless you intended to go through with it.”

After this exchange, according to Lee’s aide Captain John Mercer, who was in fact present, Washington simply “passed him by” and continued on.

Postwar accounts of the meeting between the two men would have Washington calling Lee a “damned poltroon,” and swearing “until the leaves shook on trees.” Lafayette and Charles Scott, respectively, passed these versions on. Neither of them was there when it happened, so their accounts must be viewed as pure exaggerations. Neither was a fan of Lee.

There is also an accepted version of the exchange in which Lee was subsequently relieved of command and sent to the rear of the army. This is simply another myth. Lee remained on the field and helped organize and conducted a delaying action to buy time for Washington to bring the main body of the army onto the field and form along Perrine Ridge. The American chieftain personally placed men under Wayne into a protruding section of woods known as the “Point of Woods” and the returned command to Lee, who in turned prepared a defensive line further west along a fence line dubbed the “Hedgerow.” As Washington galloped back to Perrine Ridge, Lee was left in command of all troops on that part of the battlefield. Before departing, Lee promised his commander that, “I myself should be one of the last to leave the field….”

Lee’s rearguard south of the Englishtown Road near the Point of Woods and along the Hedgerow, was short, but vicious and valiant, and it bought Washington the time he needed to form up his line of defense in their rear. It was some of the bloodiest fighting to occur that day, and as Lee pulled his men back in the direction of Perrine Ridge, he was the last one to personally retire in front of the enemy. He had kept his promise and helped turn the tide of the battle. The British would not attempt to storm the American position on Perrine Ridge.

When Lee returned to the main American line he was ordered by Washington to reform his shattered command around Englishtown. He had not been relieved of duty on the spot, but as time passed that hot afternoon, Washington ordered Baron von Steuben to ride west and assume command of Lee’s troops. Effectively, Charles Lee would never lead troops on a battlefield again. The event that transpired next is widely remembered by students of history. At his own request, Lee was court-martialed in early July under the charges of disobedience of orders, misbehavior before the enemy, and disrespecting Washington in several letters written following the battle. In August, he was found guilty on all three charges and ordered to return home for the next year.

Had Lee simply kept silent following the battle, his status within the army probably would not have been put into question. Because he had verbally attacked and disrespected Washington by asking for an apology after the fact, Lee drew attention to himself and went to war with the commander in chief. It did not become a matter of clearing his own name or satisfying his ego. In the army’s and public’s eyes, it became Lee vs. Washington. That was a fight that the former could never win. It could not just be swept under the table anymore. Someone had to lose, and that, of course, was Charles Lee.

History loves its villains, and Charles Lee makes a good one if he is to be studied only at the surface. Dig deeper and a complicated, but very brilliant and capable man can be discovered. His service at Monmouth, the defining event in his life, is not one of cowardice and insubordination that has been remembered. His subordinate officers failed him when the battle was initiated, and despite this, he was able to help turn a potential disaster into an American victory with his stand at the Point of Woods and Hedgerow. His legacy has been tainted by myth and history, but in the days following the battle of Monmouth, this was all initiated at his own doing. However, as with many individuals in history, actions speak louder than words. On the battlefields of the Revolutionary War, Lee’s actions would have spoken enough for him if he allowed them to.

Further Reading:

-

A Handsome Flogging: The Battle of Monmouth, June 28, 1778 By: William R. Griffith, IV

-

George Washington’s Nemesis: The Outrageous Treason and Unfair Court-Martial of Major General Charles Lee during the Revolutionary War By: Christian McBurney

-

Renegade Revolutionary: The Life of General Charles Lee By: Phillip Papas