Molly Pitcher and the Battle of Monmouth

On June 28, 1778, a vicious battle raged several miles west of present-day Freehold, New Jersey. It included some of the longest sustained combat of the Revolutionary War and also witnessed the largest field artillery duel of any battle. Present along the American gun line situated on top of Perrine Ridge was 23-year-old Mary Ludwig Hays, who accompanied her husband, William, and the gunners of Captain Francis Proctor’s company of the 4th Continental Artillery. By day’s end her exploits became that of legend, and the story of a courageous woman known to history as “Molly Pitcher,” was born.

Mary Ludwig was born in either Pennsylvania or New Jersey on October 13, 1754. She married a barber, William Hays, who later enlisted in Bucks County, Pennsylvania in a company of Pennsylvania Artillery when war with Great Britain erupted. As was common in 18th century armies, Mary joined her husband as a “camp follower,” and assisted the unit through various chores in camp and on the march. In 1777, the company became part of the 4th Continental Artillery and joined George Washington’s Main Army.

While it is near impossible to piece together the story of Mary Hays in the year that preceded the battle of Monmouth Courthouse, Colonel Thomas Proctor’s 4th Continental Artillery was hotly engaged at the battles of Brandywine (September 11, 1777) and Germantown (October 11, 1777), which almost certainly means that Mary was in or near the fighting. She most likely suffered through the hardships of the winter encampment at Valley Forge as well.

By June 1778, the next campaign season was about to commence as Henry Clinton’s British army in Philadelphia evacuated Philadelphia and embarked upon an overland march across New Jersey toward the safety of New York City. On June 20, the lead force of the Continental Army, commanded by Major General Charles Lee, crossed the Delaware River at Coryell’s Ferry (present-day Lambertville, New Jersey) and began the advance in the direction of the British. Mary would have followed with Washington and the main body over the river on the 21st or 22nd.

By June 27, Lee’s vanguard was within striking distance of Clinton’s army encamped around Monmouth Courthouse (Freehold). He had orders to march the next morning and pin the rear of the British force into place so Washington could bring up the main body and deliver a blow that would hopefully result in a decisive victory for the Americans. Lee departed the next morning as Clinton also began to continue his march to New York City, but the former made contact with the British rearguard left behind, and the battle of Monmouth commenced.

Lee deployed his battle line just west of Monmouth Courthouse, and the sight of the Americans forced Clinton to turn Charles Cornwallis’s Division around to confront the enemy. Without orders from Lee, several American brigades pulled out of line and began retreating west, causing the entire line to begin falling back as the British pursued. Riding ahead of the main body, Washington began to see his men marching in the wrong direction. Learning what was transpiring in front of him, the commander-in-chief galloped ahead and found Lee.

The two general met and exchanged words in what has gone down as one of the most controversial meetings of two battlefield leaders in all of American history. Washington immediately began forming a delaying force nearby and asked Lee to do the same. As Cornwallis’s division continued their advance, these American troops left behind were tasked with buying time for the Continental army to establish a defensive position and artillery line atop the strategic high ground, Perrine Ridge, further to the west. They succeeded in their mission. It was at this crucial moment that Mary entered the fighting with her husband and Capt. Proctor’s company.

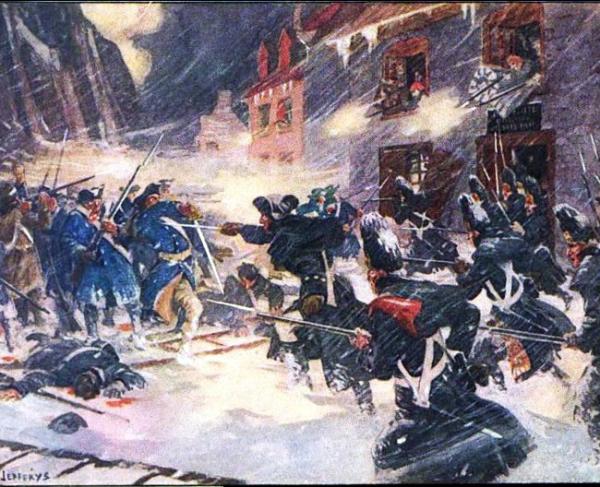

As soon as Henry Knox began deploying his cannon into position along the ridge, the American artillery, a dozen or more pieces, let loose a devastating fire against the advancing British line. The shock of the barrage and the sight of the Continentals formed up on Perrine Ridge ground the British pursuit to a halt. Clinton, himself, was on the field at this time and he immediately ordered ten cannon into position to respond to the Americans. For the next two hours, the artillery of both armies dueled across the fields of the Derek Sutfin farm. On the far-left end of the American line, Proctor’s guns were in action. The legend of “Molly Pitcher” was about to be born.

Mary’s husband and his comrades kept up their fire as the cannonballs flew through the air and slammed into the ground along Perrine Ridge. “If any thing Can be Call’d Musicial where their [sic.] is so much danger,” one American officer recalled of the bombardment, “I think that was the finest musick [sic.] I Ever heard.” Though loud, the exchange did little damage to the men of either army. The Americans simply hugged the earth, while the British hunkered down behind the rise of ground their artillery was deployed. For the gunners, the heat, rather than enemy shot and shells, proved to be the real danger as many fell from exhaustion and heat stroke due to the strenuous conditions (temperatures that day exceeded 100℉).

There are many versions to the stories of Mary Hays’s exploits that hot June afternoon. All of them agree, however, that she was right in the thick of things. As the battle raged, she was seen everywhere, running pails of water to the men from a spring behind the ridge (thus the possible origin of "Molly Pitcher;") running ammunition to Proctor’s gunners; and she was recorded as helping to load and fire her husband’s gun with his crew, most likely after William was wounded or incapacitated from exhaustion. Joseph Plumb Martin, a member of Colonel Joseph Cilley’s battalion positioned along the fence near Mary, remembered seeing a woman during the cannonade who “attended . . . the piece the whole time.” A British cannon shot even carried away the lower part of her petticoat. Through it all, the American line on Perrine Ridge stood firmly. The battle of Monmouth ended as Clinton extracted his men from the field to continue the army’s march to New York City. Washington’s Continentals were left in control of the battlefield.

Word of the woman who courageously assisted Proctor’s artillerymen quickly spread throughout the ranks. It is said that Washington promoted her to a sergeant in appreciation for her service. Later in life, she received a veteran’s pension to further confirm the tale of her heroism at Monmouth. Though she never fought in another battle following that summer, “Sergeant Molly,” had given her fair share in the cause of independence. She lived out the rest of her life in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and following her death in 1832, she was laid to rest in the Carlisle Old Graveyard next to her second husband. In 1916, a portrait statue was erected atop her gravesite. It was sculpted by Philadelphia artist, J. Otto Schweizer, a man responsible for some of the statues that can be admired at Gettysburg National Military Park in southcentral Pennsylvania today. To be memorialized in this manner is a fitting way to honor the service and devotion of a true hero of the American Revolutionary War.

Related Battles

325

381