Malvern Hill: Then & Now

The American Battlefield Trust had a chance to talk with Robert E.L. Krick, Historian at the Richmond National Battlefield Park and an acknowledged expert on the Seven Days Campaign, about the historical importance of the Battle of Malvern Hill and the current state of this 1862 battlefield.

The Battle of Malvern Hill was the last battle of the epic Seven Days Campaign in 1862. How would you categorize the state of the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac prior to this battle?

Robert Krick: I think both were pretty thoroughly used up. Continuous operations of that sort were unfamiliar to the armies in Virginia in 1862. Not many of the regiments in either army could be called hardened veterans—just a few of Stonewall Jackson’s units and the handful of regiments that had fought at both First Manassas and Seven Pines. Beyond that, the business of fighting and marching every day was new for most of the soldiers, and we can only imagine its effect on them. The battles between June 26 and June 30 also produced nearly 27,000 casualties, which is a sobering sum at any point, but especially at that early stage of the Civil War.

For the Army of Northern Virginia I’m sure the euphoria associated with the series of battles between June 26 and June 30 helped to offset the fatigue. The details of those fights, win or lose, were beyond the realm of most soldiers, but even the most incurious man in the ranks realized that they were driving the mighty Army of the Potomac from the gates of Richmond, that momentum was on their side, and that the campaign was going to end successfully for the Confederate cause. All that remained was to determine the degree of the Confederate victory. The Army of the Potomac had little to buttress its morale toward the end of the week of action, but I think it’s dangerous to paint too bleak a picture. As the men quickly pointed out after the campaign, and for years beyond, they had fought well at Mechanicsville, Gaines’s Mill, Savage’s Station, and Glendale. They, too, knew that in the grand scheme of things they were being whipped, but I’ve seen little evidence that the rank and file of the Army of the Potomac had become defeatists by July 1 at Malvern Hill. Instead, they welcomed the opportunity to fight from a superb defensive position, and most hoped that the Confederates would be imprudent enough to attack them.

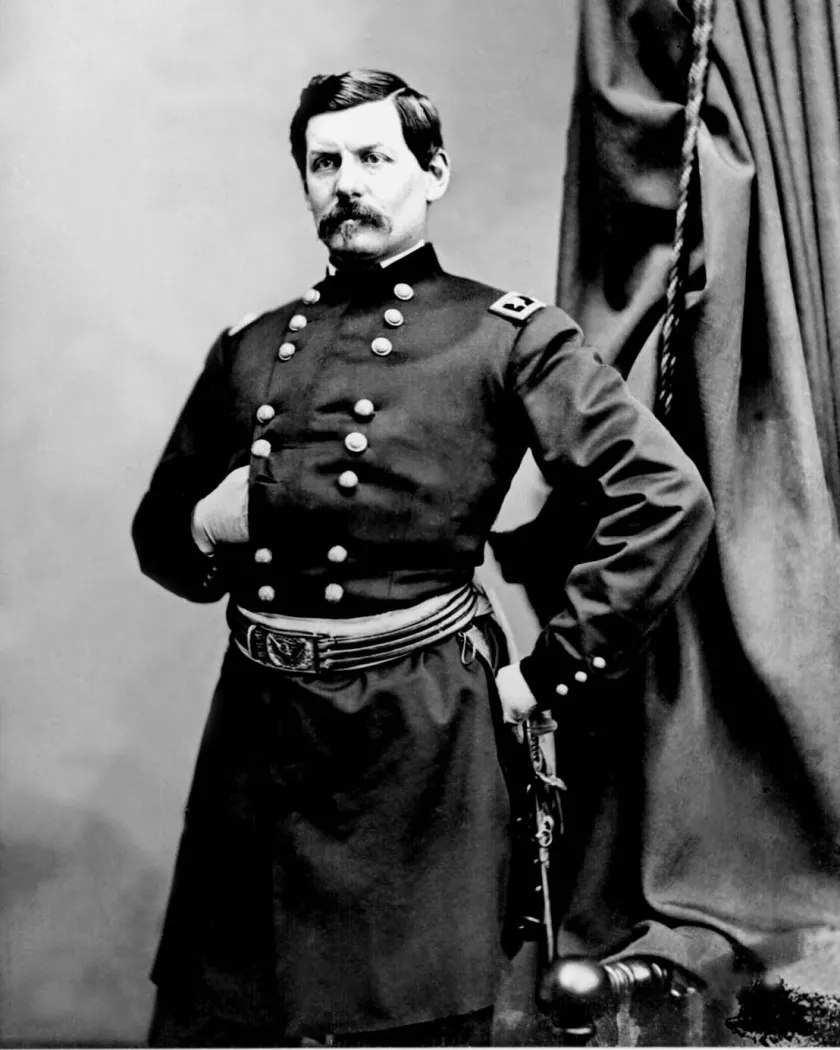

I’m not sure that the same could be said for army commander George McClellan. His own fragile personality was not suited to a series of battles like the Seven Days, and the characteristics of his generalship that had stood him good stead before carried little weight during these battles. His men did not know that he’d abandoned them the day before Malvern Hill, but senior officers not part of McClellan’s own clique were aware that events had spiraled beyond his control. It’s fortunate that Malvern Hill was such an outstanding place to fight a defensive battle. Geography gave the Northern army the help that its commander could not.

From all accounts, the Union position at Malvern Hill was a tremendously strong one. With almost 250 Union cannon and clear fields of fire, how could Lee have expected a victory at Malvern Hill? In hindsight, was he too reckless?

RK: The story of how the Confederates even came to launch attacks at Malvern Hill is tremendously complicated, and I don’t think anyone yet has truly unraveled the details. The Union position was indeed a tremendously strong one. Its only defect, of sorts, was that the crest of the hill did not extend very far. It’s only about 900 or 1000 yards across, from the very steep western edge of the bluff to the gentler eastern edge. McClellan drew his primary line of defense across that narrow neck in order to get the maximum effect of an incredible field of fire. In return, he only had room to deploy perhaps 30 or 35 cannon, and two divisions of infantry. He had virtually endless reserves stacked up to the rear, awaiting the call to action, but his actual front was not too substantial.

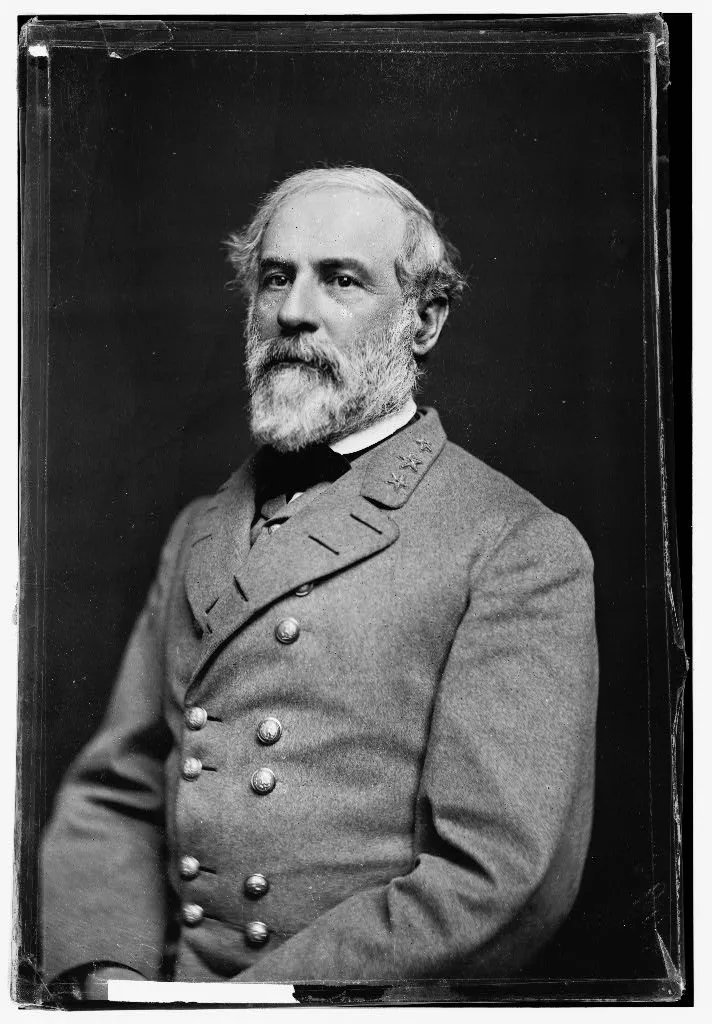

It seems clear that General Lee’s attack did not evolve the way he expected. There’s some evidence that he had given up on the idea of making a direct attack altogether. We know that he was extremely frustrated and perhaps even angry about his inability to achieve an overwhelming victory the day before at Frayser’s Farm—or Glendale, as its known in some quarters of the country. Perhaps he gave his combative spirit too much leash on July 1st. Clearly he would have been better served by stepping back and avoiding the deadly temptation at Malvern Hill. But we also have to guard against working backward from the results—from using hindsight to connect the dots. In truth, Lee did not plan the attack at Malvern Hill. He was not even on the ground when it began. He was off on a reconnaissance of his own, looking for a way to flank McClellan’s army. Botched orders and misunderstandings, combined with poor staff work, triggered the terrible charges at Malvern Hill. Lee can’t be excused entirely. It was his army, and some of the bungling came from his headquarters, but it’s important to realize that Malvern Hill is not analogous to Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, for example, as is so often said. It was not a carefully designed, choreographed episode, but rather an ill-coordinated improvisation that began almost on its own. So in retrospect I think it’s fair to say that perhaps Lee was too reckless in letting his army get into such a mess in the first place. But I don’t believe that he expected victory, nor is there any real evidence that the battle developed the way he intended. On the contrary, he probably was disappointed that the attack started at all.

Malvern Hill is known as a lopsided victory where the power of the Federal artillery was most profound. Given all this advantage, how did the Union army still lose more than 3,000 men at this battle?

RK: That casualty figure always is disconcerting. It challenges our traditional interpretation of the course of the battle. For more than a century historians have summed up Malvern Hill as a classic example of the dominance of artillery. Poorly organized waves of Confederate infantry struggled across open fields into the teeth of a terrifying, numbing wall of destruction roaring from the muzzles of those Union cannon. For anyone looking to summarize the story of the battle in a sentence or two, that would be an accurate portrayal: Federal cannon blasting Confederate infantry. And without question Malvern Hill was a decisive Union victory. No Confederates reached the line of cannon, let alone threatened the integrity of the Union position atop Malvern Hill. At no point did Lee’s army stand on the verge of any success that afternoon. Not even temporary success. Yet the casualty figures, as you point out, were not as lopsided as they should have been. The ratio is about five-and-a-half to three. Under those conditions, how could the Confederates have inflicted 3000 casualties on General McClellan’s army? I think the answer lies in a closer look at the tactics.

Both conventional wisdom and modern scholarship have proved that the Confederate artillery was, for the most part, ineffectual. I believe that the vast majority of those 3000-or-so casualties came from Confederate small arms, carried by determined infantrymen who had dodged death long enough to reach effective rifle or smoothbore range. Eyewitness accounts from the Union ranks make it clear that periodically a wave or two of Confederate infantry would get close enough to the Union cannon to be dangerous. On those occasions, the artillery fell silent and the nearest brigade of blue-clad infantry advanced out in front to deal with the problem. That’s how the four regiments in Charles Griffin’s brigade incurred more than 500 casualties, for instance. A few Confederate brigades got within revolver range. It’s pretty frightening to think of what they endured just to get there and to have the opportunity to engage in a firefight with opposing Union infantry.

If Lee had decided to forego battle at Malvern Hill would McClellan still have evacuated the Army of the Potomac from the Richmond area? If so was this battle necessary?

RK: If Lee had reined in his army on July 1, rather than forcing the matter, there is no doubt that McClellan would have moved on to the James River that night anyway. In one respect the battle occurred because the head of McClellan’s army already had reached the river, and stood in no real danger. After 100 hours of stressful retreating, he was safe. The gunboats of the United States Navy protected him. Malvern Hill afforded him the opportunity to salvage something at the end of a dismal week. Had there been no battle, the Army of the Potomac would have moved on to Harrison’s Landing on the river and I think subsequent events would have proceeded just as they eventually did anyway.

There was a great deal of bluster in certain quarters of the Union army about the aftermath of Malvern Hill. I would never, ever care to be misidentified as a George McClellan supporter, but I’ve always failed to see the merits of the argument that excoriates him for not counterattacking toward Richmond the day after Malvern Hill. The entire Confederate army—still some 65,000 men—stood astride his path. Logistics and supplies still dictated the operations of the Union army, and every stride his men took toward Richmond carried them three feet farther from a supply base that hardly even existed. Unless someone cares to claim that McClellan’s own worn out army could have defeated Lee with a head-on attack and swept through the fortifications outside of Richmond, all in one amazing swoop, then I see no sequence of events where McClellan had any substantial reward for attacking after Malvern Hill.

Over the years, you have had a chance to make an extensive and detailed study of the Seven Days Campaign. How has your perception of the Battle of Malvern Hill and the Seven Days Campaign evolved?

RK: Well, after nearly 20 years of thinking about the campaign or its component battles virtually every day, at some level, I’ve come to a better recognition of just how irregular the campaign was. Not many events in the Eastern Theater of the Civil War are comparable. After the first collision at Mechanicsville on June 26, both commanders had to cope with so many variables, so many moving parts, that I wonder just how much strategy and informed decision-making they indulged in. It is fairly clear, now, that Lee and McClellan only had the haziest notions of precisely what was occurring across the broad canvas of operations east and south of Richmond. The Confederates struggled to even find useful maps. McClellan had indulged in so much rhetoric and posturing over the preceding months that I doubt he had the ability to clearly see and understand anything by the end of June.

On a related front, though, my perception of the individual battles of the Seven Days has changed considerably. A lot of that has to do with preservation. With preservation comes access to the ground, and with battlefield tramping, as CWPT members know, comes enlightenment. This is most apparent at Frayser’s Farm/Glendale. Most of that battlefield was entirely inaccessible to all of us until its recent preservation. I’ve walked it repeatedly in the past couple of years, and still have a tremendous amount to learn, but the process of matching soldiers’ written accounts to the actual ground, and the ensuing moment of comprehension, is one of the most pleasing things in my professional life. The same process of discovery has occurred at Malvern Hill, too, although it has not been as abrupt nor as dramatic. Preserving the ridge where Magruder’s artillery stood, clearing that ground, recognizing the elevation for the first time, and ultimately seeing it with a few cannon in place, was extremely gratifying. And instructive.

Many of us think of the Union position at Malvern Hill as being atop a steep precipice. How does the real topography of the battlefield compare with this widespread assumption?

RK: I’ve been at the battlefield on tours with hundreds of folks making their first-ever visits to Malvern Hill after years of reading about it, and their reaction always is the same. They’re disappointed that the ground is not steeper. “Where’s the hill?” is the common phrase as they step off the bus or out of their car. The steepest sides of Malvern Hill are the southern end, which is privately owned and quite a distance from the main battlefield, and the western end. Some soldiers referred to that western edge as “Malvern Cliffs,” and by Virginia standards it is fairly precipitous. But that slope is obscured by trees today. Most visitors stop at the top of the hill for their first experience and after shaking off their disappointment about the elevation, they usually begin to recognize the undeniable defensive advantages. Malvern Hill is a better position than the crest of Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, or The Coaling at Port Republic, to give two famous examples. Unlike those places, Malvern Hill’s defenders had a completely unobstructed field of fire. No trees to block lines of fire, and almost no adjacent low ground beyond the reach of the cannon. The majority of the Confederate attackers faced approximately 1000 yards of completely open ground, without any substantial dip or wrinkle to offer even temporary respite or shelter. Elevation was good for defenders on Civil War battlefields, but long, gently sloped fields of fire were even better. Combine the two and you have Malvern Hill.

When visiting the Malvern Hill battlefield today, what would a visitor be able to see and do today?

RK: Because of the preservation successes there, Malvern Hill battlefield has become the most visitor friendly battlefield in this part of Virginia. And unlike most of the other Richmond-area battlefields, Malvern Hill has sweeping vistas that make understanding and appreciating the ground somewhat easier. It is those very same viewsheds that helped to shape the course of the battle 147 years ago. Richmond National Battlefield Park maintains a loop walking trail that extends for nearly two miles. A couple of parking lots along the way provide access at different points. If one parks at the foot of Malvern Hill, near the ruins of the historic Parsonage building, the trail follows the Confederate attack up the northern slope of the hill and then swings along the Union line before returning to the Parsonage. Some visitors choose to park at the crest of the hill, along the Union cannon line, and walk the trail in a different sequence, leaving the Confederate attack route for last. About two dozen signs presently exist along the trail, which is important because the Park Service does not staff the site year round. During summer months visitors often will encounter a park employee giving talks or leading tours on site, but for most of the season visitors are on their own. There is not a single monument on the battlefield, the veterans having exhausted themselves erecting granite memorials elsewhere. In some respects that makes Malvern Hill even better, as it is uncluttered and nearly pristine.

How does the Malvern Hill battlefield today compare with its state on July 1, 1862?

RK: Thanks to some aggressive scene restoration, Malvern Hill now looks very much like it did in 1862. This is a critically important point. Battlefield visitors ask over and over, at Malvern Hill and everywhere else, “what did this look like during the battle?” In recent years the outstanding work at Gettysburg has received a lot of well-deserved attention, but many of the Virginia battlefields have been working incrementally toward that same ideal for several decades. I can remember when I was a little boy and the deadly fields around the Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania were covered in trees. That’s so long ago many folks don’t remember that. At Malvern Hill the change is almost as dramatic. Several dozen acres have been returned to their original open condition. It is almost impossible to exaggerate the effect that has had on understanding the site. One of the many by-products of that was the ability to place a few cannon on the small hill where the Confederates tried to build up their own line of artillery during the battle. That ground was covered in trees until the early 1990’s. The only real remaining imperfection is the presence of a large body of trees on the western slope of the hill. They mask the steepness of the hill and prevent anyone from really appreciating that side of the battlefield. Because of the steepness of the hill, it is very unlikely that the Park Service ever will be able to return that part of the battlefield to its 1862 appearance.

The battlefield also has six original roads or road traces and a handful of historic house sites that lend character and definition to the landscape.

Over the years, the Civil War Trust has helped to save 770 acres of the Malvern Hill battlefield. Could you tell us more about the historic significance of all these saved acres?

RK: Since its creation Richmond National Battlefield Park has owned about 130 acres of the battlefield. That includes the crest of the hill where the Union artillery stood, plus some of the ground immediately in front. Someone visiting the battlefield as recently as 20 years ago could not possibly have ended their visit with a full understanding of the ground or the battle. Most of the land was inaccessible, much of it in heavy forest. Now, with virtually 1000 protected acres, we have sewed up every piece of ground across which the Confederates attacked. The site where Stonewall Jackson deployed his artillery remains unpreserved, but all of the infantry attack zone is saved. To think of it another way, twenty different Confederate brigades participated in the attack at one time or another, and the paths of all twenty can be followed today on [Trust] or National Park Service property.

From the Union point of view, the achievement is nearly as impressive. There is more land connected with the Confederate attackers than the Union defenders because the Southerners attacked across a wide arc. Even so, thanks to CWPT, we now have all of the ground where the III Corps waited in reserve, under fire. In addition, [the Civil War Trust] has preserved the land across which most of the reinforcements moved into combat—the Irish Brigade, Dan Sickles’s Excelsior Brigade, some of Francis Barlow’s men, and so on. Preserving battlefield land is the critical step, of course, but putting that ground into good condition and making it accessible to the public are really gratifying achievements that are part of the long-term legacy of the [Trust's] preservation work.

The Civil War Trust has made great preservation progress in recent years at the adjacent Glendale/Frayser's Farm battlefield, too. What opportunities has this created for visitors to the two battlefields, both now and in the future?

RK: The Frayser’s Farm/Glendale battlefield of June 30 abuts Malvern Hill to the north. Despite that fact, the two engagements were separate events. When the fighting ended at sunset on the 30th the armies remained in contact, but without any real action, until 2:30 the following afternoon. So it’s not appropriate to think of these as one running battle artificially separated by the calendar. They each had a well-defined beginning and end. Even so, because of their proximity I think they probably will be treated by visitors in the future as one large episode. The permanent salvation of most of the Frayser’s Farm/Glendale battlefield has created a corridor of 3.1 miles of contiguous preserved land.

Today someone could stand on the ground defended on June 30 by Phil Kearny’s Union division at the northern end of the Frayser’s Farm/Glendale battlefield and walk south all the way to the ground where Kearny’s division waited in reserve on the southeastern shoulder of Malvern Hill on July 1, all without leaving [Trust] or National Park Service property. In the process, that pedestrian would travel along the entire length of the Union line on June 30, through the Confederate reserve positions at Malvern Hill, up to the jump-off point for Lee’s attacks on July 1, along the path of the Confederate charge, up the hill to the Union cannon line, and beyond. It’s a pretty incredible situation, and something that was utterly unimaginable even five years ago.

Such a trail does not yet exist. In fact, most of the Glendale/Frayser’s Farm battlefield is not routinely open to the public, though of course that will change. Fundamental questions like parking, trail networks, and historical signs still have to be addressed. But those things are inevitable, and everyone connected with the preservation of these places, at every level, should feel proud of their accomplishments and look forward to the day when these two battlefields in tandem are the crown jewels of Civil War battlefields in central Virginia.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

2,100

5,600