In 1860, as the Civil War approached, a German immigrant named Eberhard Gottlieb Anheuser decided to leave soap and candle-making to buy the struggling Bavarian Brewery in St. Louis, Missouri. His investment saved the brewery, and a year later his daughter married another German immigrant, Adolphus Busch, who lent a hand and later his name to the still successful brewing company that we know today as Anheuser-Busch. While Anheuser-Busch’s longevity is unusual, it was just one of many breweries established in the United States before or during the Civil War that would face challenges posed by the conflict.

While many of mid-nineteenth century brewers lived far from the front-lines of the conflict in midwestern cities, including Madison and Milwaukee, they were not immune to the obstacles of war. By August 1861, the federal government introduced the nation’s first income tax, which was expanded in 1862 to apply to all manner of goods: sugar, almonds, iron, leather, silk, figs… and beer. Angered by the necessary increase in prices and lower profits, some brewers tried to cheat the system, reporting falsely deflated sales and facing off against local tax officials. Those who were caught in the act were shut down and some breweries’ inventories were simply seized until they could prove that all taxes had been paid. Other brewers banded together in protest. In August of 1862, German-American brewers in New York City formed the United States Brewers’ Association, the first American industry trade group. By 1863, the association had grown into a national organization that strove throughout and after the war to modify the legislation.

As breweries across the north fought increased taxes on their craft, other brewers operated in areas directly affected by the more violent aspects of the war, including Eberhard Anheuser’s brewery in St. Louis, Missouri. As the urban center of a highly contested border state, St. Louis was the setting for riots, military encampments, and sectional violence. Yet, despite the conflict erupting around the city’s breweries, the influx of soldiers proved to be a blessing for brewers—a whole new market of men looking for ways to kill time and the trauma of battle through alcohol. This increase in demand even inspired some breweries to expand; in 1864, wealthy brewer Adam Lemp constructed a new plant to keep up with demand, making his company one of the largest breweries in St. Louis and ultimately becoming the Falstaff Brewing Corporation, which survived into the 1990s.

Far away in the Deep South, Union-occupied New Orleans’s brewers enjoyed the hordes of soldiers in the city and one soldier of the 77th Illinois Infantry recorded the generosity of a local brewer who had sent beer to his regiment. In November 1862, however, the city’s military governor, General Benjamin Butler, issued an order forcing the closure of all businesses selling intoxicating substances. Soldiers in Union-held Memphis recorded a similar experience—one soldier of the 1st Nebraska wrote that the provost guard’s strict policy towards beer limited him to secretly drinking bad lager. As this soldier revealed, however, these bans on beer were not completely effective, especially since lager’s characterization by some as “non-intoxicating” meant that in some cases, it did not qualify to be banned at all.

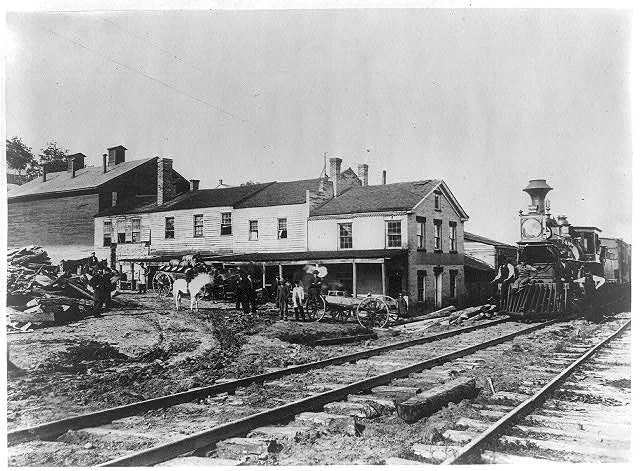

While these military bans could try to keep soldiers from alcohol, beer remained an important part of 19th century medicine. The US Sanitary Commission recommended it as a cure for digestive issues resulting from camp life. It also had a cheering effect, boosting the morale of recovering soldiers. Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, had its own brewery even in a city under martial law that forbid the sale and consumption of intoxicating beverages to its residents. In Madison, Wisconsin, one man recorded the joy of the soldiers recuperating in the local hospital when the local Rodermund Brewery gave them four kegs of beer.

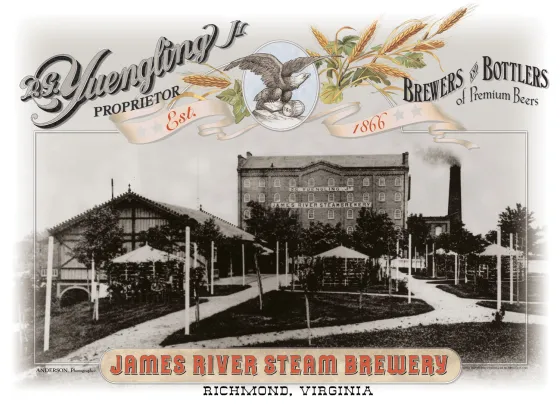

Just as the Civil War posed both challenges and opportunities to brewers, the brewing industry after the war has had its ups and downs. Initially after the war, breweries across the nation began to thrive again. In February 1866, Richmond became the home of Yuengling’s James River Steam Brewery, the ruins of which can still be seen today. The invention of pasteurization in the 1870s increased the shelf-life of beer and opened new markets beyond brewers’ immediate communities. In the decade following the Civil War, the number of breweries in the US sky-rocketed, cresting 4,000 by 1873.

But trouble came again with the Panic of 1873, which contributed to the end of Yuengling’s Richmond branch. Countless other breweries succumbed a few decades later during Prohibition, the Great Depression, and the rationing and shortages of World War I and II. Yet, somehow through all of this, a few breweries survived. Today, Anheuser-Busch is joined in longevity by Yuengling, founded in Pottsville, Pennsylvania in 1829, and Pabst Brewing Company, founded in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1844. And now, these well-known names make beer alongside the highest number of domestic brewers since 1873—bringing back the landscape of small breweries of 150 years ago.