Music is a universal language. It has spoken to all societies and cultures throughout history and will continue to do so far into the future. People gravitate towards certain sounds, instruments, beats, and lyrics, catapulting some pieces of music firmly into popular culture. Despite four years of terrible strife and horrendous losses, numerous songs and airs became ingrained in popular culture during the American Civil War. Even against such a backdrop as a civil war, music, musicians, and the role of music in the United States from 1861-1865 was just as diverse as it is today. Western art music experienced what later became known as the Romantic Era. Closer to home, musical styles such as sacred music, brass bands, and minstrel shows were popular in both the North and South. Although divided by conflict, the universal language of music often stretched across the great chasm the war produced. This is even true with how civilians, and later soldiers, listened and were exposed to different types of ensembles and pieces during this time period. They attended concerts or minstrel shows as a source of entertainment. They sang hymns and spirituals at church services and religious events. Military bands and the music they played inspired patriotism and fighting spirit. It was played on the march before and after battle. Military bands also played music that instructed soldiers when to eat, go to bed, and even charge into battle. Even though the universality of music broke down regional ideological divides during the war, the distinctiveness of each popular genre needs its own exploration.

Lasting from approximately 1830-1900, the Romantic Era of Western art music was defined by the exploration and expansion of expression and the inventiveness of techniques and instruments to achieve it. Symphonies became bigger and longer, piano playing reached a new level of virtuosity, music drew from art and literature, and operas were even more dramatic. Composers of the era included: Pytor Illich Tchaikovsky, Johannes Brahms, Gustav Mahler, Giuseppe Verdi, Richard Wagner, as well as many others. People living in large metropolitan areas with resident symphonic orchestras, or visiting orchestras, not only could have heard these composer’s latest works, but also works of earlier and equally famous composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Johann Sebastian Bach.

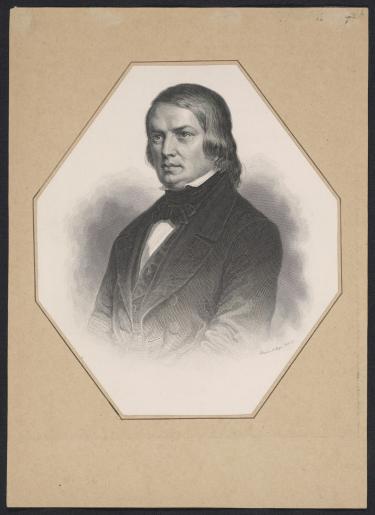

One of the most renowned Romantic Era composers was Robert Schumann. A musical prodigy, Schumman began piano lessons at the age of ten. His teacher, Friedrich Wieck, quickly recognized his extraordinary ability. Wieck’s influence did not end there. He also saw and pushed Schumann’s aptitude for composition during the peak of the Romantic Era. As Schumann’s compositional talents grew, however, his piano playing diminished. The budding musician and composer lost hand dexterity and movement. Although some scholars and even contemporaries subscribe to the loss of his dexterity and movement to a mechanical finger strengthening device, others argue it was due to a medical condition. Yet, this unfortunate event only made him more focused on writing. Schumann’s focus can best be seen in his completion of Symphony No. 1 (Spring Symphony) in only four days. In total, Schumann composed 148 musical works for piano, voice, chamber ensemble, and orchestra during his brief 46 years. He died on July 29, 1856.

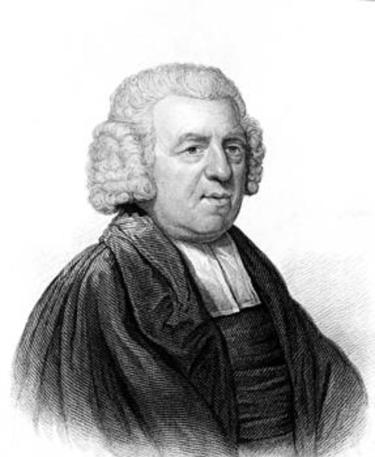

For a larger portion of our country during the antebellum and Civil War era, an opportunity to hear orchestral music was limited. That does not mean that what average Americans listened to was any less diverse, however. The diversification of musical genres in the United States during this era spread and took hold regionally. One such genre, shape note, began in New England but spread and took hold in the South. Commonly heard in religious congregations or social settings, shape note music was written in such a way to help singers find and move between different pitches within a song. The distinct symbols were designed to help singers distinguish the various scale degrees and solmization syllables. The four main notes in every shape note song are Fa, Sol, La, and Mi. Four part singing, soprano, alto, tenor, bass, was now more easily achieved by singers with little to no musical training. A popular shape note song of this period was “New Britain.” This complex tune was originally written as a poem titled, “Amazing Grace,” in 1772 by a recently-ordained Anglican priest, John Newton. In 1835, William Walker then set the poem to the popular tune, “New Britain.” The origins of this work are unique for a number of reasons, most notedly, however, for its encapsulation of Newton’s incredible journey to the priesthood. Furthermore, the poem’s words, now song lyrics, spoke of Newton’s disapproval of slavery and the slave trade, a stark difference to the beliefs of the region in which this genre flourished.

Diversification of music and genres continued throughout the era and the country. In Louisiana, for example, African slaves brought with them a tradition of drumming and drum circles. Many West African countries such as Mali and Senegal have deeply rooted traditions and ritualistic practices. The art of drumming was a way to tell stories and pass down important cultural aspects within individual communities. Djembes, made from hollowed out tree trunks, were the main instrument used in traditional African drumming. Performers, also known as griots, used their hands to strike the drum, creating different sounds. Oftentimes, singing, and dancing accompanied the drumming in a very rhythmic style. African musical traditions, then, were brought to the United States as part of our country’s reliance on the slave trade. As many vestiges of these people’s lives were stripped from them, their traditions and culture often lived on through their music. West African rhythms, timbres, and even instruments blended with other genres across the southern states to create unique sounds and styles that became popular during the nineteenth-century.

As religious fervor swept throughout the country in the 1830s and 1840s, spirituals and hymns became a commonly heard form of music. Slaves added their unique drumming and rhythms to these traditional hymns and created their own spiritual music. African American spirituals were a way for slaves to gather and sing their praises together. Since slaves were not allowed to worship in a church setting, they gathered and held meetings at “praise houses.” Typically, spirituals were sung in the style of call and response. The spiritual leader led the congregation in both song and worship as they explored and embraced Christianity in their new world. One of the most popular spirituals is “Swing low, sweet chariot” composed by Wallis Willis in the mid to late nineteenth-century. “Swing Low,” as well as many others, are still recognized today due to the collection and publication of spiritual music that began in the late 1860s. Thus, the popularity of the spiritual song movement during the nineteenth-century ensured its place as one of America’s largest and most significant forms of folk music.

The influence of African musical traditions impacted more American musical genres than just spirituals. Secular music also utilized many African instruments, timbres, and musical traditions brought to the United States by slaves. During the antebellum years, white composers wrote music based on these traditions and performed traveling shows that became known as minstrels. This genre of music and entertainment was a combination of song, dance, and comedic dialogue performed by white actors in blackface. These shows presented caricatures of African Americans, mainly of the southern plantation slave or a northern freeman. A popular song and dance, character, and later, full minstrel show was “Jim Crow.” Made famous by Thomas D. Rice, the struggling entertainer was one of the first performers to use blackface. Rice’s show took off, with “Jim Crow” reaching audiences all across the country as early as 1828. Although intended to be light-hearted entertainment, the portrayal of these caricatures has negatively remained as several offensive and racial stereotypes into the twenty-first century.

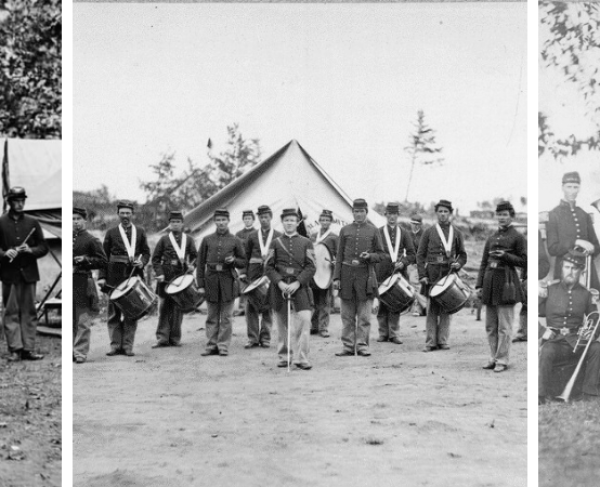

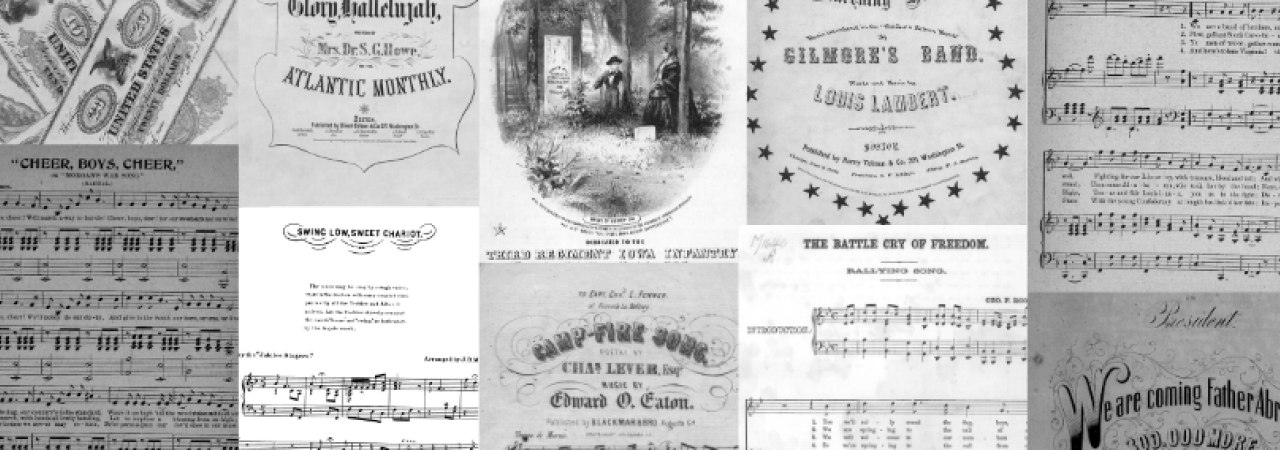

Another genre that grew into popularity before the Civil War were brass bands or community bands. Once the armies were formed and in the field, the music of military fife and drum corps, as well as brass bands, became popular again, both within the armies and on the home fronts that supported them. Troops on the move and in camp used music in a variety of ways. Music provided a sense of comfort and allowed all men on both sides to transcend the great political and ideological divide that separated their country. Popular tunes were accessible and familiar to the common man from both the North and South as many soldiers did not have the opportunities to immerse themselves in live music found in metropolitan cities. Thus, bandsmen played popular tunes such as: “Eatin’ Goober Peas,” “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” “Battle Cry of Freedom,” as well as many others. These songs were known for their steady beats and motivational words which helped the soldiers press on during tough times and long marches.

Singing, playing, and hearing music allowed troops to reminisce about peaceful times at home with family and loved ones, bond, and temporarily escape from the horrors of battle. Author Kenneth Bernard wrote, “In camp and hospital they sang -- sentimental songs and ballads, comic songs and patriotic numbers … The songs were better than rations or medicine.” Military bandsmen were not the only ones to provide music, though. Some soldiers brought their own banjos, fiddles, and guitars. Out of these instruments came many popular camp tunes of the era, including: “Lorena,” “Tenting on the Old Camp Ground,” “Vacant Chair,” and “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” to name a few.

The musical world around soldiers and civilians during the antebellum and war years provided support, guidance, escape, and entertainment. As is true with music today, people from that time period gravitated toward music that mimicked or identified with their feelings at that particular time. And, by doing so, broke the political, ideological, and regional divides brought on by the Civil War. Yet, it was some of those differences of thought and place that added to the musical landscape of the nineteenth-century, the “peculiar institution” being just such an example. With the country embroiled in war, music remained important to everyone, at home and on the front lines. General Robert E. Lee, commander of the famed Army of Northern Virginia, agreed, “I don’t believe we can have an army without music.” In a larger sense, then, we cannot understand one of the most important moments in our history without understanding its popular musical stylings.

Further Reading

- Music of the Civil War Era By: Steven H. Cornelius

- Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War By: Christian McWhirter

- Songs of the Civil War By: Irwin Silber