And fair the form of music shines, That bright, celestial creature, Who still, 'mid war's embattled lines, Gave this one touch of Nature.

John Reuben Thompson

These lines, written by Virginia poet John Reuben Thompson (1823-1873) in "Music in Camp," echo the sentiments of no less an authority than Confederate General Robert E. Lee, who once remarked that without music, there would have been no army. The New York Herald agreed with Lee when, in 1862, a reporter wrote, "All history proves that music is as indispensable to warfare as money; and money has been called the sinews of war. Music is the soul of Mars...."

In his 1966 classic Lincoln and the Music of the Civil War, Kenneth A. Bernard calls the War Between the States a musical war. In the years preceding the conflict, he points out, singing schools and musical institutes operated in many parts of the country. Band concerts were popular forms of entertainment and pianos graced the parlors of many homes. Sales of sheet music were immensely profitable for music publishing houses on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Thus, when soldiers North and South marched off to war, they took with them a love of song that transcended the political and philosophical divide between them. Music passed the time; it entertained and comforted; it brought back memories of home and family; it strengthened the bonds between comrades and helped to forge new ones. And, in the case of the Confederacy, it helped create the sense of national identity and unity so necessary to a fledgling nation.

Bernard writes, "In camp and hospital they sang -- sentimental songs and ballads, comic songs and patriotic numbers....The songs were better than rations or medicine." By Bernard's count, "...during the first year [of the war] alone, an estimated two thousand compositions were produced, and by the end of the war more music had been created, played, and sung than during all our other wars combined. More of the music of the era has endured than from any other period in our history."

Songs of the Armies

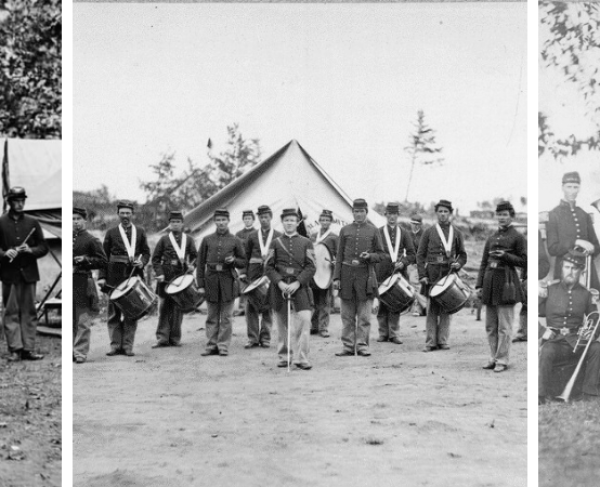

Songs and music of the Civil War covered every aspect of the conflict and every feeling about it. Music was played on the march, in camp, even in battle; armies marched to the heroic rhythms of drums and often of brass bands. The fear and tedium of sieges was eased by nightly band concerts, which often featured requests shouted from both sides of the lines. Around camp there was usually a fiddler or guitarist or banjo player at work, and voices to sing the favorite songs of the era. In fact, Confederate General Robert E. Lee once remarked, “I don’t believe we can have an army without music.”

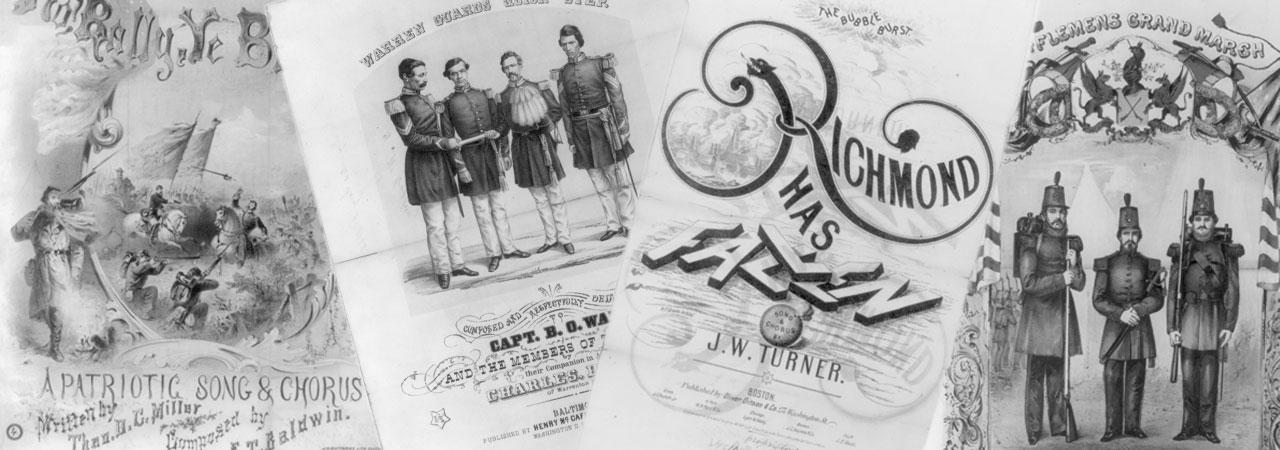

There were patriotic songs for each side: the North’s "Battle Cry of Freedom," "May God Save the Union," “John Brown’s Body” that Julia Ward Howe made into “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and the South’s “Dixie” (originally a pre-war minstrel show song), "God Save the South," "God Will Defend the Right," and "The Rebel Soldier". Several of the first songs of the war, such as “Maryland! My Maryland!” celebrated secession.

“The Bonnie Blue Flag,” another pro-Southern song was so popular in the Confederacy that Union General Benjamin Butler destroyed all the printed copies he could find, jailed the publisher, and threatened to fine anyone—even a child—caught singing the song or whistling the melody. The slaves had their own tradition of songs of hope: “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” the words said guardedly—meaning follow the Big Dipper north to the Underground Railroad and freedom.

Soldiers sang sentimental tunes about distant love—the popular “Lorena” and “Aura Lee” (which in the twentieth century became “Love Me Tender”) and “The Yellow Rose of Texas”—and songs of loss such as “The Vacant Chair.” Other tunes commemorated victory—“Marching Through Georgia” was a vibrant evocation of Sherman’s March to the Sea. Some even sprouted from prison life, such as "Tramp, Tramp, Tramp."

Soldiers marched to the rollicking “Eatin’ Goober Peas;” they vented their war-weariness with “Hard Times;” they sang about their life in “Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground;” they were buried to the soulful strains of “Taps,” written for the dead of both sides in the Seven Days’ Battles. When the guns stopped, the survivors returned to the haunting notes of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.”

After Robert E. Lee surrendered, Abraham Lincoln, on one of the last days of his life, asked a Northern band to play “Dixie” saying it had always been one of his favorite tunes. No one could miss the meaning of this gesture of reconciliation, expressed by music.

—Adapted from Encyclopedia of the Civil War edited by John S. Bowman (Dorset Press, 1992) and Music in the Civil War by Stephen Currie (Betterway Books, 1992.)

Further Reading:

- Lincoln and the Music of the Civil War By: Kenneth A. Bernard

- Music in the Civil War By: Stephen Currie

- Confederate Music By: Richard Harwell

- The Singing Sixties: The Spirit of Civil War Days Drawn from the Music of the Times By: Willard A. Heaps and Porter W. Heaps