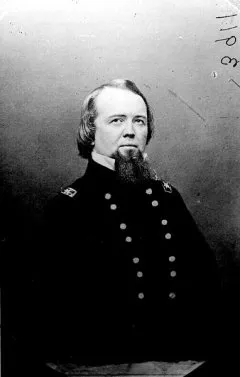

Major General John Pope came to Virginia in June 1862 not just to win battles, but to change the war. Heretofore, the Union general George B. McClellan had managed things in Virginia in a cautious, gentle, gentlemanly sort of way (the war “should be conducted upon the highest principles known to Christian civilization,” he wrote in mid-1862). That approach had not worked; the Union war effort stalled that summer. President Abraham Lincoln summoned Pope to reinvigorate the Virginia front with outright aggression, while setting aside some of the “Christian principles” McClellan had espoused.

By mid-summer 1862 it was clear (at least to Lincoln and his administration) that 80 years of sectional discord would not be resolved merely by the clash of armies on the battlefield. Instead, the Union war effort needed a broader scope, targeted not just at Confederate armies, but at the Southern economy, civilian morale, and the institution of slavery. It was clear to Lincoln – and most other Republicans in Washington – that George B. McClellan, who had commanded the Army of the Potomac for the last year, was not the man to wage that sort of war (McClellan steadfastly argued that “military power should not be allowed to interfere with the relations of servitude”). Thus came John Pope, a Lincoln friend, West Point graduate, and career military man with the unusual distinction of being Republican in his leanings and sympathetic with Lincoln’s inclination toward emancipation. Pope would not replace McClellan outright – that carried too many political implications – but instead Lincoln hoped he would supersede McClellan with success.

Pope’s first substantive orders to his “Army of Virginia” dictated not the movement of his troops, but the behavior of his army. He permitted men under his command to requisition food from Virginia farmers. He demanded oaths of loyalty from male civilians within Union lines in Virginia. He dictated that local civilians would be held liable for damage done by Confederate raiders. By modern standards, these measures seem mild. But in mid-summer 1862, they seemed radical and, to some Unionists, offensive. Leading the chorus of disapproval were McClellan and his closest confidant, Major General Fitz John Porter. Porter labeled Pope an “ass,” and predicted, “if the theory he proclaims is practiced, you may look for disaster.”

Another military officer in Virginia likewise reacted to Pope’s verbose presence in Virginia: Robert E. Lee, the newly minted commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Lee called Pope a “miscreant” (strong language indeed from Lee) and declared that he “must be suppressed.”

Accomplishing that presented a daunting task for Lee. He had commanded his army only since June 1 (only 25 days longer than Pope had commanded his Union army) and still faced the vestiges of the campaign he had inherited from his predecessor. McClellan’s army lay just 25 miles east of Richmond on the James River, huge and menacing, though (from Lee’s perspective) happily sluggish. Eighty miles northwest of Richmond hovered Pope’s new army of about 55,000 men. Lee wanted desperately to vanquish Pope and clear the way for a bold move into Maryland. But before he could do that, he needed to ensure quietude from McClellan. The Union high command in Washington ultimately guaranteed that when, on August 3, Union General-in-Chief Henry Halleck ordered McClellan off the Peninsula, directing him to shuttle troops to Pope as quickly as possible. Lee now had both his opportunity and challenge: He could move against Pope but needed to defeat him before his and McClellan’s armies could merge. If Lee failed – if Pope subsumed McClellan’s forces into his own – Lee would face a huge force that even his emerging brilliance would have been hard-pressed to suppress.

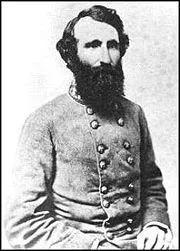

In late July 1862, Lee started his move. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s wing of the army marched first, closing on Pope’s advance corps near Culpeper and defeating the Federals in a stubborn battle at Cedar Mountain on August 9. Lee and Longstreet soon followed, and by August 17, the armies had commenced a river dance – first along the Rapidan, and then along the Rappahannock. For a week the two armies sparred, moving crab-like northward, Lee looking constantly for his chance. On August 25, along the banks of the Rappahannock, he found it in dramatic form.

Scouts spotted an unguarded crossing above Pope’s right flank, near a crossroads called Amissville. Better yet, they determined that a series of roads could lead the Confederates to Pope’s rear, where havoc might inspire Pope to retreat or, perhaps, lurch into an unwise engagement to Lee’s advantage. Lee turned to Jackson, who had made himself famous with a string of stunning marches in the Shenandoah Valley, and directed his wing commander to undertake a daring march. Over the next two days – August 25 and August 26 – Jackson and 24,000 men (just under half the army) would cover 54 miles in 36 hours. They arced around Pope’s right, through the Bull Run Mountains at Thoroughfare Gap, and plowed into Pope’s supply line at Manassas Junction, on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.

While Jackson’s men pillaged the Union depot at Manassas, Pope responded to the crisis just as Lee hoped he would. Pope’s army – newly supplemented by arrivals from the Peninsula – sprawled out across the landscape in search of Jackson. “We shall bag the whole crowd,” Pope declared of Jackson’s force. But, as Pope’s army descended on Manassas Junction on August 27 and 28, 1862, Jackson skirted northward to the old Manassas battlefield. There he took a position along the base of Stony Ridge, using a never-finished railroad bed as an earthwork. He would be well positioned to meet Lee and the rest of the Confederate army, soon to come through the Bull Run Mountains. And, more importantly, he would be in position to lure Pope into battle.

On August 28, all of the elements of Lee’s and Jackson’s plans and hopes fell into place. Lee, with James Longstreet’s wing of the army, arrived at Thoroughfare Gap that evening; they would fight their way through and join Jackson the next morning. Pope, who by now was thrashing about the Virginia countryside in search of Jackson, conveniently strode to within Jackson’s grasp. Late that afternoon, Jackson received word that part of Pope’s army was passing eastward on the Warrenton Turnpike, just in Jackson’s front. The general mounted his horse and rode to have a look. Some of the federals in column spotted this lone horseman pacing his horse, watching them pass, but they paid no mind – not imagining it could be Jackson himself. After minutes of examining the Union column, Jackson made his decision. He galloped back to his command post. To the waiting officers he announced, “Bring out your men, gentlemen!”

Jackson had all the advantages, but suffered one uncertainty: the quality of the Union men he was about to engage in battle. They were the soldiers of John Gibbon’s brigade – Indiana and Wisconsin troops – soon to be famous as the Iron Brigade. As Jackson’s guns opened on the Union column, Gibbon wheeled his brigade off the Warrenton Turnpike. Northward through the fields and woods of John Brawner’s farm his Midwesterners marched, over the next half-hour assuming a line nearly a half-mile long. If Jackson assumed the Yankees would respond timidly, he was wrong. Gibbon’s men would produce one of the sharpest fights of the war.

Whether from overconfidence, poor performance, or just bad luck, Jackson’s lines came into battle haphazardly, allowing the Federals to match them regiment for regiment. The result: a bloody stalemate featuring some of the most intense musketry fire any of these men had ever seen – morphing into what John Gibbon called a “long and continuous war.” Confederate Brigadier General William B. Taliaferro recalled, “In his fight there was no maneuvering, and very little tactics – it was a question of endurance, and both sides endured.”

Tactically, the fight at Brawner Farm must have constituted a disappointment for Jackson. He vastly outnumbered Gibbon’s command, yet throughout the battle could not muster a significant numerical advantage at the point of contact. By battle’s end, the dead lay with their feet “on a well-defined line,” testimony to the uncommonly brutal and static combat.

But on another level, Jackson achieved with the battle precisely what he wished: he sent a signal to Pope. “I am here,” he seemed to say. “Come and get me.”

Related Battles

14,462

7,387