A Missed Opportunity

by Ian Michael W. Rogers

The July 20, 1864 Battle of Peachtree Creek was the first in a series of bloody battles for Atlanta during July and August of 1864, and part of the larger Atlanta Campaign in which the Confederate Army of Tennessee defended North Georgia against Sherman’s invading Union army. Peachtree Creek also marked Confederate General John Bell Hood’s first battle as an army commander and a radical shift in Confederate strategy. On July 20, 1864, in just under three hours, nearly 4,000 Americans were killed, wounded or missing in Hood’s first attempt to drive Sherman’s army from the gates of Atlanta. Although well envisioned, the attack failed in large part due to poor communication and execution.

During the 1860s, the Peachtree Creek battlefield was a rural area north of Atlanta, with fighting along Collier and Peachtree Roads (Peachtree Road was known as “Buckhead Road” in 1864). Today, the hallowed ground of Peachtree Creek battlefield lies beneath residential neighborhoods, strip malls, parking lots, and fast food restaurants. It is in the heart of Atlanta between Midtown and Buckhead where tens of thousands of people live and work. The area in which Confederate General Clement H. Stevens was mortally wounded is now a gas station, restaurants and parking lots. A 2010 National Park Service report stated that “The battlefield of Peachtree Creek is unrecognizable; Metropolitan Atlanta has obliterated the battlefield landscape.” Yet development and “obliteration” of the battlefield landscape were not inevitable.

In 1900, thirty-six years after the battle, a formal proposal was presented to Congress as “H.R. 946, A Bill Establishing the Atlanta National Military Park.” Earlier that year, the Atlanta Business Men’s League published a seventy-five plus page illustrated pamphlet: The Proposed Atlanta National Military Park (Proposed Military Park).

The proposal would have set aside approximately 1,275 acres for battlefield preservation, covering substantial portions of the Peachtree Creek battlefield. The Proposed Military Park would have been roughly 3 miles north of the year 1900 Atlanta city limits. Peachtree Creek was selected instead of Bald Hill, the site of the July 22, 1864, Battle of Atlanta. The area around Bald Hill was already “thickly populated and the property would be difficult to obtain and necessarily high in price.” The land at Peachtree Creek was cheaper, not extensively developed, and the Proposed Military Park would be connected with other battlefields around Atlanta through a system of driveways. The proposal argued that “it is due these men, and it is due their comrade of long ago, the men who gave up their lives a willing sacrifice on the sacred altar of devotion to country, home and loved ones, that the historic scenes of their hard-fought battles be marked and preserved.”

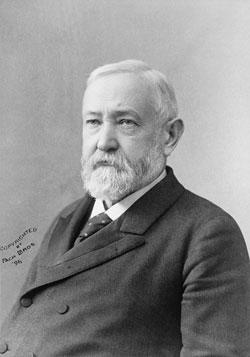

The Proposed Military Park garnered the support of notable Union and Confederate veterans. Former President Benjamin Harrison fought at Peachtree Creek. Thirty-three years old in 1864, Harrison led his brigade forward and helped stop the fierce assault made by Featherston’s Mississippi brigade. In 1900, Harrison wrote: “The military incidents connected with the investment and ultimate capture of Atlanta are certainly worthy of commemoration and I should be glad to see the project succeed.”

Other supporters included Confederate Generals J.J. Finley, William Bates, Stephen D. Lee, and Alexander P. Stewart as well as Union generals Smith D. Atkins, Orland Smith, John Palmer, John Coburn and Daniel Butterfield, among others. Several of these supporters were veterans of Peachtree Creek and had a personal stake in the proposal. Union General John Palmer commanded the Fourteenth Corps at Peachtree Creek and clashed with Alexander P. Stewart’s Confederate Corps, who suffered the brunt of the Confederate casualties on July 20, 1864 with more than 1,400 killed, wounded, or missing. Endorsed by various camps and posts of the United Confederate Veterans and the Grand Army of the Republic, the proposal marked a concerted and unified effort by key veterans of both the North and South to preserve battlefield land while many veterans were still alive.

In his support for a military park, former Union cavalry commander General Smith D. Atkins stated “I like the idea of a National Military Park…It is altogether a modern idea to turn battlefields into military parks…not in glory for the victory of the Union forces, not in celebration of Confederate defeat, but in honor of American valor in blue and gray, for we are all Americans, proud of American heroism on American battlefields….for we are again a united people, with one flag and one destiny.” Former Confederate General Stephen D. Lee agreed. “There can be no doubt of the good effects of their establishment in binding up the great States and obliterating all sectional differences.”

The time period of the proposed Atlanta National Military Park represented both the spirit of reunion and the zenith of veteran-led battlefield preservation. Yet anyone driving up Peachtree Road today knows that an Atlanta National Military Park was never established. Sources indicate the enterprise failed in Congress due to cost, reportedly $119 per acre. After recently funding five National Military Parks, Congress was wary of further battlefield appropriations.

By the 1920’s, planned neighborhoods began to dramatically change the historical landscape. Brookwood Hills, Ardmore Park, Collier Hills, and Loring Heights, (named for Confederate General William Loring), transformed the battlefield. In the early 1930’s, the Atlanta Journal reported on one final proposed military park. This proposal failed in part due to nearby Kennesaw Mountain’s emergence as a National Battlefield Park and the deepening economic downturn of the Great Depression.

The failure to preserve Peachtree Creek battlefield holds an important lesson, applicable to not only Atlanta’s urban battlefields but those of Nashville, Fort Stevens in Washington D.C., and others. When an opportunity for preservation presents itself, it must be given serious attention because it may never come up again.

For Peachtree Creek, the window of opportunity closed many years ago. Yet as the 2010 National Park Service report concludes: “Opportunities for commemoration and interpretation exist.” The Civil War Trust’s Atlanta Campaign Battle App Guide® is a wonderful asset for exploring urban battlefields that were not preserved. At Peachtree Creek, Bald Hill, and Ezra Church, digital media enables visitors to imagine the landscape 150 years ago.

Atlanta’s 14.5-acre Tanyard Creek Park sits within a major section of the fighting at Peachtree Creek. An open field in the park marks the location through which Featherston’s Mississippi brigade charged up and over Collier Road and engaged future United States President Benjamin Harrison’s Union brigade. This field is a prime location for new historical markers.

Recently, more than 100 people trudged through a torrential downpour to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Peachtree Creek. Residents and visitors alike are curious about what happened here. At the local level, groups such as Buckhead Heritage Society are working to raise the public’s awareness and understanding of Peachtree Creek through recognition, interpretation, and preservation. Buckhead Heritage is in the process of implementing an Interpretative Master Plan that will include the Battle of Peachtree Creek through innovative historical markers, exhibits, and digital media. Just two miles north of the battlefield at Peachtree Creek is the Atlanta History Center, with one of the largest depositories of Civil War artifacts on display.

While the battlefield at Peachtree Creek has been permanently altered, significant opportunities for commemoration and public history exist--to finish what the proposed military parks failed to do—to give meaning and recognition to this hallowed ground.

Special thanks to the following persons who provided information and insights for this article:

Erica Danylchak, Executive Director, Buckhead Heritage Society, Atlanta, GA.

Dr. Gordon Jones, Museum Studies Program Director and Senior Military Curator, Atlanta History Center.

Related Battles

1,750

2,500