Momentous Results at Cross Keys

Robert K. Krick

Through the first week of June 1862, General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson steadily fell back up the Shenandoah Valley, under pressure from two widely separated Federal columns. His monumental triumphs at Front Royal and Winchester, on May 23 and 25, had unhinged Unionist aspirations for control of the Valley, but now fresh Northern forces pursued him in quest of revenge.

Because Jackson did not have enough troops to overcome the geographical verities that afflicted Confederate possession of the northern reaches of the Valley, he retired southward. Union General John Charles Fremont followed him directly. Another enemy force under General James Shields paralleled Fremont, well to the east.

The towering, generally impassable, Massanutten massif played a key role in setting the stage, separating the Valley into two discrete halves for fifty miles. So did the two arms of the Shenandoah River, wending northward on either side of the big mountain, and only bridged infrequently.

Shields moved through the smaller valley east of Massanutten; Fremont followed Jackson west of the mountain, and in direct contact. Watercourses swollen by a late spring far wetter than the norm helped Confederates thwart the pursuit.

By June 6, Jackson had retired far enough southward to pass the upper nose of Massanutten. From Harrisonburg, opposite the mountain's southwestern corner, the Confederates slid southeast toward the confluence of the North River and the South River at Port Republic; those two rivers edged the village and met to form the South Fork of the Shenandoah. (Anyone glancing at a map of the region will wonder why some geographer in ancient times did not denominate it the "East Fork of the Shenandoah," but South Fork it was and is.)

At Port Republic–"Port" in the local parlance--they would be directly in front of Shields's force, when it pushed that far up the Valley. Keeping Fremont and his troops from following close behind became an essential element for Jackson's success. If they arrived around Port Republic in time to collaborate with Shields, Jackson faced dire odds and the potential to be assailed from both sides.

Retarding Fremont's advance commenced on June 6, with more loss than gain. As Unionists edged out of Harrisonburg to follow the Confederates, a rearguard stymied them in the southeastern outskirts of town: but the legendary Southern horseman Turner Ashby died in the skirmish. Ashby had been a general for just a few days and enjoyed enthusiastic support from his troopers, although his inattention to organization, discipline, and detail had thoroughly exasperated Jackson.

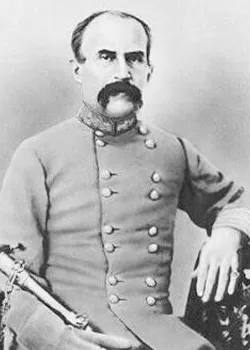

On Sunday, June 8, Stonewall prepared for the church services he so much loved as quiet early morning light bathed his headquarters at the southern edge of Port Republic. Shields had not yet shown up from due north, and Confederate General Richard S. Ewell stood athwart Fremont's path at Cross Keys, a few miles from Port, down the Harrisonburg Road.

The peaceful Sunday erupted into two crises that threatened Jackson--personally at Port Republic, and in a broader operational sense at Cross Keys. In the village, Federal cavalry raiders burst across the South River, achieving complete surprise. The Valley cavalry, ill-lead and undisciplined under Ashby's tutelage, had deteriorated even more in the immediate aftermath of his death, and failed to screen or block downstream from Port. Jackson came within a whisker of being captured himself, and some of his personal staff fell into enemy hands.

Watch our Historian Video: Stonewall Jackson's Narrow Escape from Port Republic

The exciting crisis at Port Republic exploded and then ebbed within a short interval. June 8th's serious long-term business was keeping Fremont at arm's length to the northwest, at Cross Keys.

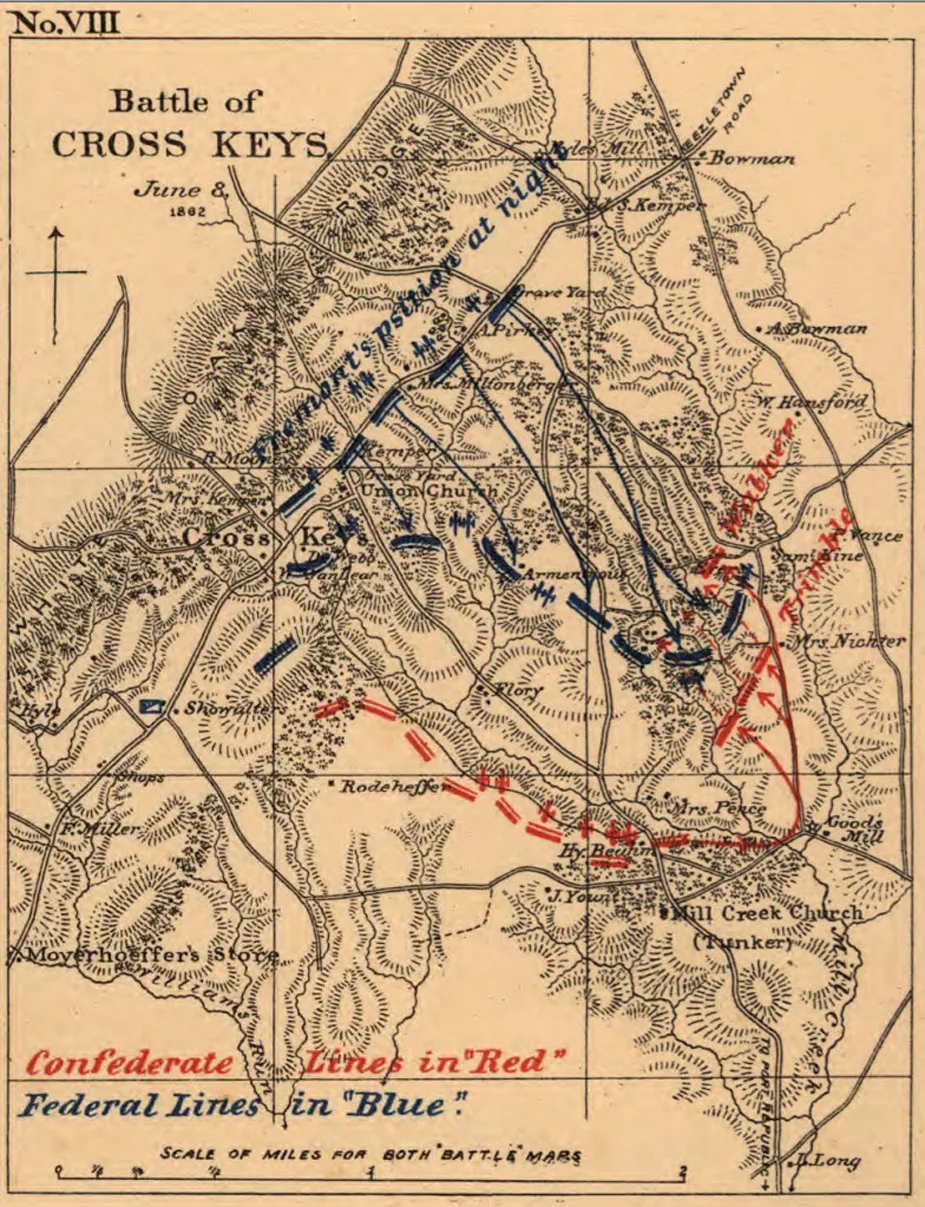

Dick Ewell's troops occupied an admirable defensive line above Mill Creek, in a region known as "Cross Keys" because of a nearby wayside tavern of that name. The Confederate line followed commanding ground, conveniently high enough above the stream to afford a magnificent field of fire onto any approaching foe. As though sculpted by nature for this military purpose, the high ground curled at its outer ends into a bit of an arc. An attacking enemy would expose his flanks to the edges of that crescent.

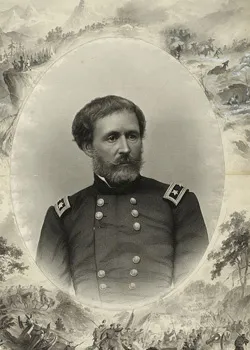

Had it not been for the unquenchable drive of General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble, the battle would have degenerated into feckless charges by Fremont's Federals, without much success—but also without much loss, leaving them ready to push toward Port Republic on the morrow, to interfere with Jackson's plans there.

Unwilling to await an attack, and eager to close with the Yankees, Trimble pushed his brigade of four regiments forward from the right (east) end of the Mill Creek line. The feisty Marylander was about the oldest Confederate general in the field in Virginia, but despite his years, among the most aggressive. At Cross Keys, by a wide margin the day's most violent action resulted from the general's ardor.

Trimble's men—one regiment each from Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and North Carolina--found cover behind a fencerow, in a perfect position to ambush any Federals who pushed forward without appropriate caution. Enough vegetation grew around the fence to provide useful camouflage.

The contour of the ground served Southern purposes even more comprehensively. Federals approaching from the north would have to drop off a plateau into a stream bottom, then climb up again to a lip that opened onto a shelf about sixty yards from where Trimble's troops crouched. Even though virtually all of the Confederate infantry still carried outmoded smoothbore muskets, at sixty yards they would be deadly.

Watch our Historian Video: Ambush of the 8th New York at Cross Keys

Precisely such an incautious advance as Trimble anticipated walked aimlessly into the Confederate deadfall, and paid a ghastly price for the error.

The 8th New York Infantry of Julius Stahel's Brigade moved toward Trimble's covert position, unaware that it lurked in their path. At this stage of the war, after more than a year of experience, advancing with skirmishers deployed to uncover the location of threats ought to have been routine. Stahel ignored that elemental precaution. Trimble had sent North Carolinian skirmishers forward, and they dutifully fired a few rounds and brought back word about the approaching attack—perfectly discharging the skirmishing role.

Many of the muskets leveled by soldiers of the 16th Mississippi, 15th Alabama, and 21st Georgia held charges of "buck and ball," comprised of a standard musket ball augmented with a few pieces of buck shot. That round would not carry far, and be nigh useless on a typical battlefield. At close range, though, the multiple projectiles would prove deadly.

Lying "flat on the ground, with their guns in the bottom crack of the fence," Southern infantry "in a quiver of excitement…saw the Germans coming up out of the hollow." A Georgian infantryman recalled the moment when "a volley from a thousand guns sounded in the air, and a thousand bullets flew to their deadly work." The fire seemed to a participant to be a "volcano more terrible than Vasuvious."

Trimble, no enthusiast for Yankee politics or culture, applauded his foes' bravery, but declared that his men's "deadly fire" had dropped "'the deluded victims of Northern fanaticism and misrule by scores."

Many, probably most, of the luckless New York men were German immigrants. The list of their dead include surnames such as Ehler, Heinicke, Wabbenhorst, Franke, Kempf, Pauli, and Schellhass. With losses of nearly 300, the 8th suffered more than one-third of the Federal casualties on the entire field.

General Trimble eagerly grasped the opportunity to pursue the survivors of the 8th New York. His yelling Confederates dashed across the fatal shelf, down into the stream bottom, up the other side, and on to the line from which the 8th had begun its ill-starred advance—some 500 yards north of the ambush site.

A Union battery under Captain Frank Buell supported the Federal position, and a Pennsylvania infantry regiment reinforced it. Trimble's men, riding the crest of a wave of momentum generated by their repulse of the 8th, pushed their advance right through the rally point. The site where triumphant Confederates troops quickly overwhelmed that stand is being preserved in 2012 by the Civil War Trust, in a preservation coup just about as impressive as Trimble's military achievement!

When another concentration of Yankees, a bit farther northwest, dissolved in the face of his advance, Trimble stood as master of the field. Characteristically, he yearned for more enemies to thrash, and spent the rest of the afternoon and evening hounding Ewell for permission to launch a further advance. Recognizing that such a move would not achieve the larger strategic goal, Ewell rejected his pleas, so Trimble rode south in a vain effort to persuade Jackson on the matter in person.

Meanwhile, the rest of Ewell's force had a far simpler day, repulsing desultory attacks on the western portions of the line, above Mill Creek, with consummate ease.

With Fremont violently overwhelmed at a crucial point, and stymied everywhere else, Ewell had deftly accomplished his mission. Jackson would have the morning of June 9 in which to defeat the Federal force approaching Port Republic under Shields, without interference from the direction of Cross Keys.

Recommended Reading: Conquering the Valley: Stonewall Jackson at Port Republic

Related Battles

684

288