Monmouth

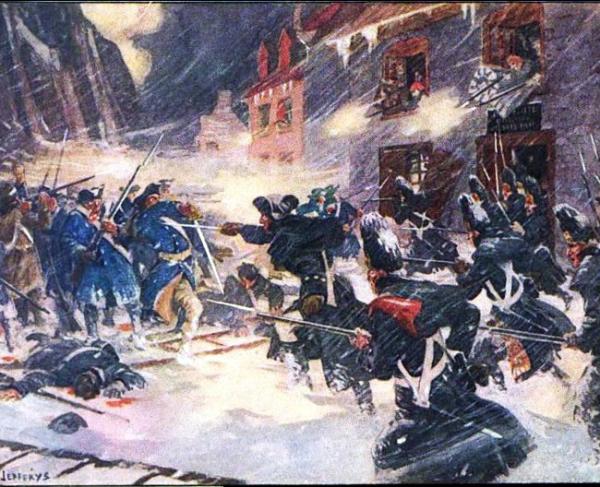

General George Washington and his subordinate Charles Lee attacked rearguard elements of the British Army commanded by General Henry Clinton, on a hot and humid June 28, 1778. Although outnumbered two-to-one, the Continental Army had undergone extensive training in the art of war during its winter encampment at Valley Forge. Charles Lee, who launched the initial attack, lacked confidence in the ability of the soldiers under his command. In doing so he ceded the initiative to his British counterpart General Charles Lord Cornwallis who commanded the rear elements of the twelve mile-long British force. What had opened as a promising assault by the Americans devolved into a potential rout as Washington encountered panic stricken Continentals fleeing from the field.

Confusion reigned everywhere as the battle ensued one veteran complaining later, “The dust, smoke… sometimes so shut out the view that one could form no idea of what was going on.” The 100 degree weather dripped with high humidity and that contributed to the confusion as orders sent were never received and in other instances officers took matters into their own hands, further confusing the American line of battle. Enraged, Washington galloped ahead of his wing and in an angry confrontation on the field of battle removed Lee from command.

Washington then rallied what troops remained to continue their assault and pursuit of the British. The delaying action led by Washington gave time for the rest of the Continental Army to come up and join the battle. Washington’s troops took a position near a ravine on the grounds of the Monmouth Court House. Washington deployed his forces with General Nathanael Greene's division securing the right flank with General William “Lord” Stirling's division holding the left. Lee’s men were turned over to the Marquis de Lafayette who kept those troops is reserve. General “Mad” Anthony Wayne assumed other elements of Lee’s command and manned Lafayette’s front. Artillery was placed on both flanks with the cannons on the right flank having the advantage to use enfilade fire should the British offer a challenge. They did.

American artillery played a significant role in the battle under the command of General Henry Knox holding off at various times repeated British counterattacks. The repeated thumping of Knox’s cannonade rent the air with an unceasing loud din.

Cornwallis attacked Stirling’s men but were held at bay by the resistance put up by a better organized and trained Continental Army. An American counterattack on the British right flank forced them back where they had to reorganize. The commencement of fighting forced Cornwallis to move his troops towards the growing fight where they engaged Greene’s men. Greene’s troops supported by some artillery stiffened their line repulsing Cornwallis and his troops.

The fighting see-sawed back and forth under the brutal June sun for several hours. Wayne’s men were attacked in his forward position by another British column. His troops, protected behind a hedge repulsed the British three times before their flank was turned. Wayne’s men retreated in good order returning to the main American line. British soldiers struggled mightily in the heat, too, each man carrying eighty pound packs and wearing heavy woolen uniforms. Continental Army Private Joseph Plumb Martin wrote in his memoirs that it was like fighting in the “mouth of a heated oven.” Many men on both sides were felled by the heat in addition to bullets.

By 6:00 pm the British called off the fight. Wayne wanted to press the fight, but Washington believed his men were “beat out with heat and fatigue” American total casualties of killed, wounded and captured numbered about 600. The British loss was estimated at 300 killed with the wounded possibly totaling as high as 700.

The British did not give Washington a chance to renew the fight in the morning, slipping away under the cover of darkness and resuming their withdrawal to New York City.

One of the most enduring legends to emerge from the history of the War for Independence is the story of the heroism of Molly Pitcher taking the place of her fallen husband who was manning one of the artillery pieces. According to the story the woman was most probably Mary Ludwig Hays who lived in the area and during the battle had been running water to the American soldiers and when her husband went down she took his place at the gun. Molly Pitcher remains prominent in the lexicon of American history.

While the Americans held the field at day's end and the British resumed their retreat most historians consider the Battle of Monmouth a tactical draw.

Most significantly, the Continental Army fought for the first time as a cohesive unit, having been expertly trained during their Valley Forge crucible by the Prussian officer Friedrich von Steuben who gave them an air of martial professionalism. That training paid off in north central New Jersey as men who endured a bitter cold winter encampment blossomed in the summer sun of 1778.

Related Battles

325

381