Gwen Spicer has cared for more than 300 historic flags in her decades-long career, with more entering her studio each year.

Symbolically, a flag is far more than a colorful banner and that meaning is not subject to physical deterioration. But the cloth itself can fray, stain, stretch and fade with time. Skilled artisans are necessary to extend the life of these objects that connect us to the past.

The flag is arguably the most significant of our national symbols. Even our national anthem is devoted to the flag in a military context, telling the story of how it still flew high above the ramparts of Fort McHenry after the battle there during the War of 1812. Such historic banners visibly bear the signs of conflict — bullet holes, vestiges of dirt and smoke accumulated in the field — as well as the ravages of time, and they resonate with us because we can conjure in our own hearts the devotion our forefathers had for them.

If anyone can be said to be intimately familiar with historic military flags, it is textile conservator Gwen Spicer, who owns and operates Spicer Art Conservation, LLC from her farmstead in upstate New York. Over the course of her career, Spicer has known more than 300 such flags — dating from 1770 through the Vietnam War and even September 11 — down to their individual stitches.

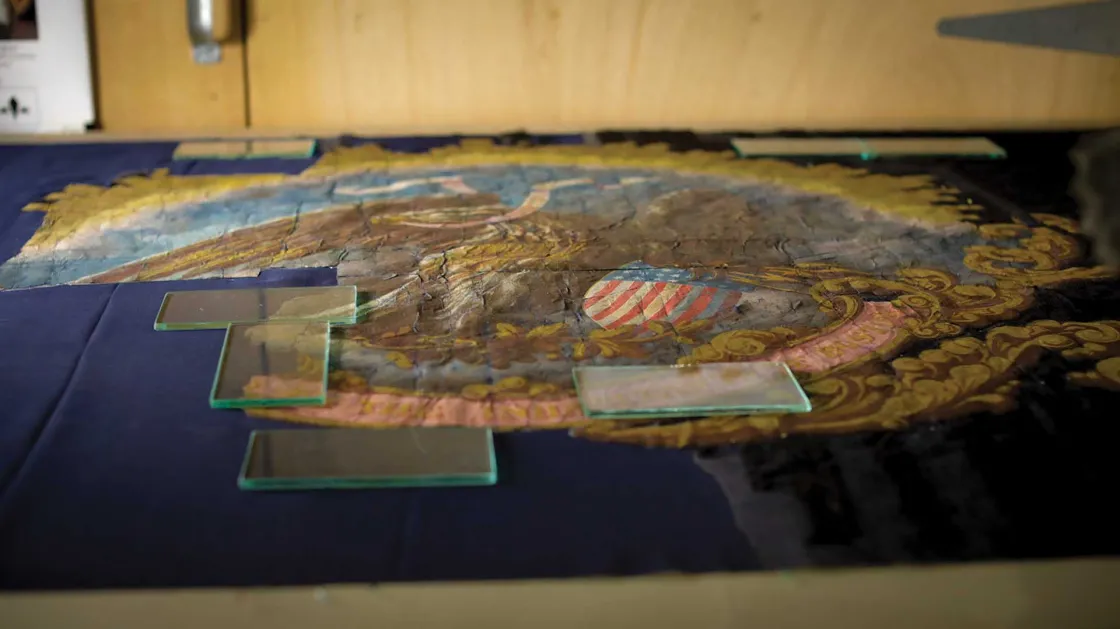

During the Trust’s recent trip to her studio, Spicer had a trio of flags on her workbenches from the collection of the West Point Museum, each representing vastly different eras and challenges. The oldest belonged to the 1832 Corps of Cadets and had significant damage to its unique base fabric. The flag of the 20th U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), carried in battle at Fort Blakely, Ala., the same day in April 1865 that the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered, was largely intact but with scattered vertical tears, especially among its field of painted stars. The heavily embroidered World War II flag that came from Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces experienced significant fading from light exposure during a past exhibition and required specialized mounting to ensure its future stability.

“Flags do tell stories, especially the older ones,” she says. “Flags of the 20th century are mass produced, whereas flags from the 18th and 19th centuries are very individual. So, each one represents a story, and with each one there is an emotional connection to the people who owned them or have a connection to them.”

For example, among the cherished, historical artifacts at the Maryland Historical Society is a regimental flag of the 4th USCT. The double-sided red, white, blue and gold flag was presented to the regiment by the African American women of Baltimore. On September 29, 1864, the banner was at the fore as the unit charged Confederate lines at the Battle of New Market Heights. When the colors went down, Sgt. Alfred B. Hilton of Co. H. didn’t hesitate. He seized both the national and regimental flags and carried them forward to the inner line of the Confederate defenses until he, too, fell. His shattered lower right leg was amputated, but the wound proved mortal, and Hilton died at Fort Monroe about three weeks later.

The citation for Hilton’s Medal of Honor — like four others awarded that day to Black soldiers — is explicit in its connection and devotion to the flag. But after more than a century and a half, the regimental flag was missing a large portion of the right side. And the rest of it was in extremely fragile condition, woven as it was of silk, with hand-painted lettering on the fabric. “It had many areas of tearing and shattering,” Spicer said of its condition upon arrival.

With each flag she handles, Spicer’s first step is to develop a conservation plan that takes into account the flag’s construction and condition — as well as the curatorial needs of the owning museum. The work is a blend of art and science; careful stitches combined with an understanding of how different fabrics react to cleaning agents or how forces like gravity and UV light will play out across years or decades of display. Often, mounts must be custom designed and fabricated to exacting specifications. And yet, as unique as each historic flag may be, the conservation of most of them starts out with careful but thorough removal of dust and particles.

“Vacuuming is a pretty standard first step,” Spicer said. “It is a small, hand-held vacuum with a range of suctions, but most things need to be vacuumed with a low suction. And I use a vacuum with a HEPA (high efficiency particulate air) filter, so that the dust doesn't get redeposited or circulated within the studio. And there’s a technique in the vacuuming. You want a motion that goes up and down versus side to side because you don’t want to add surface abrasion while you’re vacuuming.”

If necessary and if the flag won’t be harmed, it also receives a wet cleaning, often with nothing more than pure, distilled water. “Over the time that I’ve been treating things, I have tended to use less and less detergent and have learned to just use the power of water to clean things,” she said. “Because oftentimes, I’ve found that artifacts have already been cleaned in the past and sometimes have residue of detergent and soap already in them that hasn’t been fully washed out.”

Over her many years of experience, Spicer has helped develop techniques and strategies that have become standard in art conservation, if only because the field was in its early stages when she first became interested in it in the 1980s. As now understood and practiced, conservation contrasts with restoration, which might seamlessly re-create elements that have been lost. Instead, while Spicer may make small repairs when appropriate, she focuses on preserving what still remains, presenting it in the best possible light and maximizing its longevity.

But the number one rule is this: Do nothing that cannot be reversed.

Despite best intentions at the time, the damage done by past treatments can be dramatic. Another USCT flag Spicer conserved — a small, framed silk flag of the 26th USCT — owned by a small library in western upstate New York — had been adhered to a laminated board with an excessive amount of glue.

Spicer had to carefully remove several layers of the paperboard to reach the base layer. That final layer, closest to the flag, presented extreme challenges because of the likelihood of removing pieces of silk from the flag while trying to separate it from the glue and paper.

“That was not easy,” she said. “It really was not easy. The adhesive that they used was super thick and it was not soluble.” She was able to remove a vast majority of the paper, but “small areas were determined to stay” and had to be left attached to the flag, she wrote on her blog, “Inside the Conservator’s Studio.”

The conservation of most flags also involves protecting them behind UV-filtered Plexiglas. “Depending on the material, whether it is wool, cotton or silk, and depending on the amount of loss or its level of deterioration, a common technique to stabilize flags is to encapsulate them between two shear layers. And the stitching to hold the layers together goes along the seams and in the areas of loss,” she said. The flag is then secured behind the Plexiglas in an aluminum frame. Custom frames showcase unique attributes of individual flags; the 4th USCT. flag with the double-sided canton necessitated a mount with a Plexiglas window on the reverse so both sides can be seen.

Spicer’s love of textiles began in childhood with a beloved grandmother who taught her to sew and quilt. It was married to art and artifacts during a high school job in a gallery when, occasionally, a piece or object would arrive broken. “Somebody was hired to fix it, and I was like, ‘Wow! That’s the job I want. You can actually handle the art.’”

Although her technical expertise extends to all kinds of fabrics, from tapestries to uniforms to linens, flags have become an increasing specialty and passion because of how evident the meaning they carry remains across generations. “When I was working at the (National Park Service) Harpers Ferry Center decades ago for a renovation of the Gettysburg Visitor Center, it was interesting when other Park Service staff visited how they related to the flags we were working on,” she said. Working on the 4th USCT. flag further sparked a personal interest in the flags of those regiments, with extensive research to find out how many still survive. So far, she has found and reproduced 26 USCT flags on her blog, although several can be shown only as black-and-white images because that is all that survives.

No matter how many remarkable pieces she has conserved, the thrill of getting to touch the artifacts remains for Spicer each time she begins a new project or watches a visitor encounter her tangible type of history. Although she spends her days examining individual threads with a magnifying glass, she finds time to step back and wonder at how those fragile fibers can be bound into something that can last for generations — and carry such symbolic might.

“I may not be able to stop time,” she says, acknowledging that fabrics will and must deteriorate. “But I want to slow down what it does.”