The United States Colored Troops at the Battle of New Market Heights

In the early morning hours of September 29, 1864, fourteen thousand Union soldiers massed at a sharp bend on the James River known as Deep Bottom. They belonged to one of four columns operating against the Confederate capital at Richmond, its supply hub at Petersburg, and the roads and railroads feeding into each. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant planned this offensive, his latest in a now three-and-a-half-month campaign against Richmond at Petersburg. He believed that General Robert E. Lee could not both protect all along the thirty-mile front and react to declining southern fortunes elsewhere in the Confederacy.

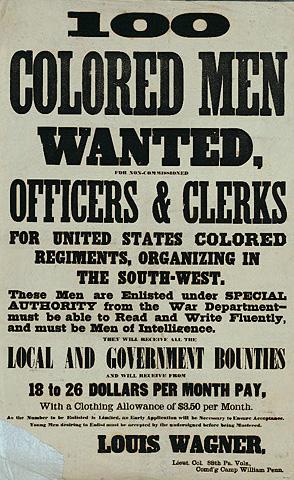

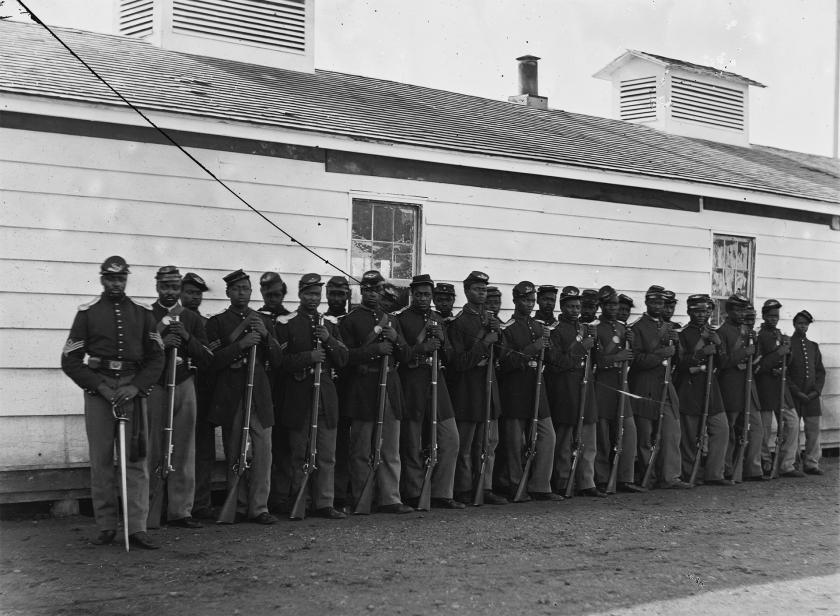

Major General Benjamin Butler commanded the Army of the James in its operations against Richmond and wrote detailed orders to coordinate his own two prongs of the offensive. He also had ulterior motives of his own. Early in the war, Butler had advocated that Union armies operating in the Confederacy should liberate any slaves they encountered as “contraband of war” and employ them in support of northern forces. President Abraham Lincoln supported this idea and signed two Confiscation Acts into law. He then boosted the decision even further with the Emancipation Proclamation, a component of which included the development of the United States Colored Troops. By the autumn of 1864, many of these black regiments (with white commissioned officers) had seen combat, and Butler envisioned a large role for the USCTS in Richmond’s capture.

Only 8,700 men opposed Butler north of the James and half were local Richmond troops not currently on the front line. The regular Confederate forces were divided between Chaffin’s Bluff and New Market Heights. A fortified camp at Chaffin’s Bluff above the James River controlled the primary roads into the city and opposed the left wing of Butler’s army. The latter meanwhile overlooked a Union bridgehead at Deep Bottom that had been established in late June 1864. Major General David B. Birney commanded the right wing of Butler’s army and received instructions to seize New Market Heights, marked by a prominent ridge below which ran the New Market Road in a northwesterly direction toward Richmond. West of the hills, Four Mile Creek flowed south before making a sharp turn to the east below the road. The stream collected the headwaters from the surrounding hills and created a marshy valley in between the Union bridgehead and Confederate defenses, two miles apart.

Brigadier General Charles Paine’s XVIII Corps division (all USCT regiments) reported to Birney and already held the Deep Bottom bridgehead on the morning of September 29. Paine advanced northward before dawn while Birney methodically distributed the rest of his men south of Four Mile Creek. At 5:30 a.m., Colonel Samuel Duncan launched the first attack against New Market Heights with his 4th and 6th USCT. The two regiments plunged downward into the swamp and continued north toward the fortified line.

The much-heralded Texas Brigade directly opposed Duncan. An additional brigade of cavalry and two artillery batteries lent their support. The Confederates held their fire until Duncan’s advance stalled in the abatis, an obstacle described by an officer in the 6th USCT as a “dense growth of light driftwood, lopped down so that stumps and trees yet cling together, forming a tangled network of limbs and trunks difficult to penetrate.” As the USCTS struggled through these obstructions, the Texans and their supporting artillery unleashed a devastating barrage. Duncan, the black non-commissioned officers, and white lieutenants all attempted to spur the men forward. but the two regiments crumbled away under the withering gunfire. Duncan was wounded four times and yielded command to Colonel John Ames.

“It was a deadly hailstorm of bullets, sweeping men down as hailstones sweep through the trees,” recalled Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood of the 4th USCT color guard, who seized the American flag after a bullet cut down its bearer. “We struggled through the two lines of abatis, a few getting through the palisades, but it was sheer madness, and those of us who were able had to get out as best we could.” Confederate accounts afterward boasted that their volleys increased in severity once they learned they were shooting into the ranks of USCTs. One Texan claimed “the word was passed along the line that they were negroes and to give them lead. Every fellow shot with as much precision as if they were at a shooting match.” The two regiments suffered 387 casualties before falling back across Four Mile Creek.

Colonel Alonzo Draper’s brigade moved forward to cover as Ames withdrew the battered infantry. At about 7:30 a.m., Paine directed these three regiments—the 5th, 36th, and 38th USCT—to attempt another charge across the same ground. Draper compacted his men into assault columns and instructed them men to not pause and engaged in a gunfight. They moved forward and pushed up to the abatis. During Duncan’s first attack, pioneers had chopped gaps through the obstructions to provide avenues to reach the Confederate lines. The second wave, however, had to also pick their way over ground strew with their fallen comrades. Many chose to seek cover and return fire, usually a certain way in Civil War attacks to lose all momentum and chance for success. Draper reported that his brigade lingered in the swamp and abatis for “half an hour of terrible suspense,” trading fire with the entrenched Confederates before surging forward once more. This time they managed to swarm up to and over the fortifications.

Ever since the battle it has been debated whether the USCTs captured New Market Heights or simply occupied vacated earthworks. Union accounts claim they wrested the position from the Confederates. Butler passionately promoted this version and personally funded the creation of 197 medals to issue to soldiers who distinguished themselves in the battle. Fourteen black soldiers additionally received the Medal of Honor for their bravery at New Market Heights. Most Confederate accounts depicted a planned, orderly withdrawal. By 7 a.m., the left wing of the Army of the James had captured Fort Harrison, the key point of the Confederate defense at Chaffin’s Bluff closer to Richmond. Southerners therefore stated that the New Market Heights garrison learned of this development and marched west to protect the capital. Their version gave little to no credit to Draper’s men for winning the engagement, perhaps the expected response from such written statements of how “the fun began” when they started to shoot “a million dollars worth” of USCTs. Certainly, such accounts would never admit if they had lost a battle to black soldiers.

Either way, Paine’s division no doubt did their part in the late September offensive. Its early promise faded, however, and the campaign lasted until April 1865. As at New Market Heights, it was characterized on the Union side by masterful logistics and inspired strategy, but inconsistent execution and a lack of at the front. Butler’s black soldiers nevertheless had demonstrated that they had invested with their lives in the cause of Union and freedom. Southern leadership had avowed that their slaves belonged to an inferior race but at New Market Heights the United States Colored Troops proved they could provide a valuable piece in Union strategy as its forces slowly strangled the Confederate citadel into submission.