A detailed view of the eagle on the back of the 4th USCT Regimental Colors

During the Civil War, Union infantry regiments carried two flags – the national colors and regimental colors – while Confederate regiments carried a single flag. Both sides also used General Guide flags, or guidons, placed on the flanks of each line of battle.

Battle flags were essential “not only for unit identification, but also for noting progress, or lack thereof, on smoke-filled battlefields,” said historian Greg Biggs, an expert on Civil War flags. “Colors led the charge and were used to rally broken units in battle. But they also served as the 'steering wheel' for regiments in line of battle.”

Soldiers who carried the colors were automatic targets and far more likely to die than a regular infantryman because the enemy eagerly shot at them not only to see the flag fall, but to demoralize the enemy and create confusion and chaos in the ranks.

“Defending the colors was very important to a regiment and losing them brought shame,” said Biggs. “It has been this way since the Roman era. The color guard were selected by the unit commander and were among the bravest men of his regiment. They also paid a tremendous price. And yet more men came forward to carry and protect them.”

An untold number of soldiers on both sides during the Civil War sacrificed their lives for their regimental flags or trying to capture the enemy’s colors. Consider that of the 1,522 Medals of Honor awarded to Union soldiers in the Civil War, more than 460 were related to valor displayed in relationship to these flags — carrying or rescuing, capturing or preventing their capture, planting them upon enemy works. A combination of logistical landmark and symbolic touchstone, each unit’s flags — typically a national flag and a state one, often personalized — were deeply prized.

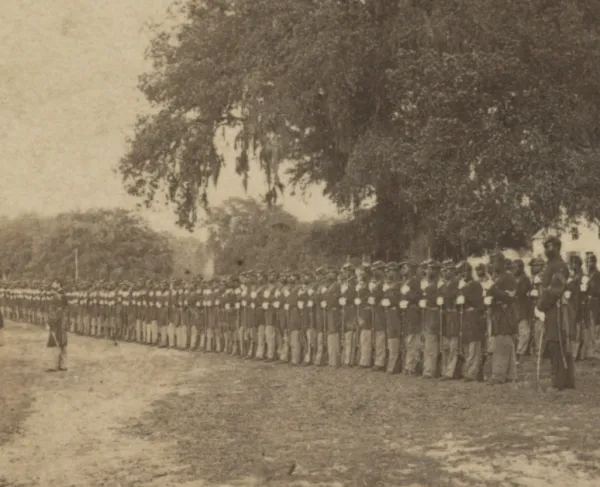

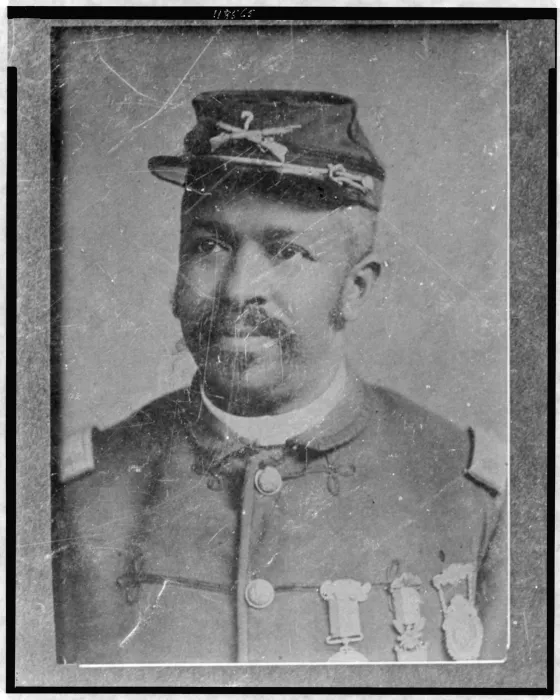

In the fierce fighting at New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, 14 Black soldiers were awarded Medals of Honor, as eight regiments of United States Colored Troops assaulted fortified Confederate lines over rough terrain and through a withering fire. More than a third of those citations — Alfred B. Hilton, Christian Fleetwood and Charles Veal of the 4th USCT, plus Thomas Hawkins and Alexander Kelly of the 6th USCT — explicitly mention flags, while that of Powhatan Beaty of the 5th USCT obscures that relevance in its brevity.

Given that they — and their bearers — were prominent targets, battle flags could be significantly damaged in combat. The ravages of time, coupled with past storage practices now considered damaging to fragile silk and cloth, mean that those flags that remain are treasured tangible links to the past.

Gwen Spicer, a leading textile conservator, has been privileged to work on the stabilization and repair of many such banners dating back to Colonial era conflicts, including one from the collection of the Maryland Center for History and Culture that flew over New Market Heights.

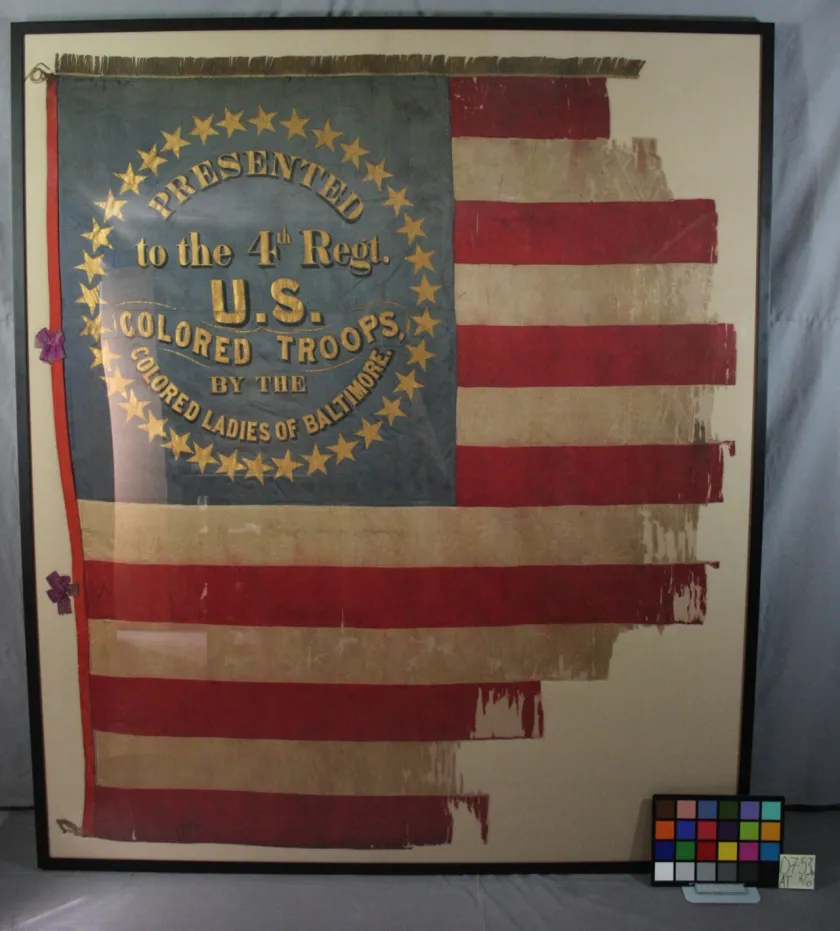

“The 4th USCT is a spectacular flag,” said Spicer, citing its hand-painted, double-sided canton. On the obverse, the blue silk boasts 35 stars and, in stylized black and gold print, Presented to the 4th Regt US Colored Troops by the Colored Ladies of Baltimore. The reverse features a painterly eagle with an interesting mix of elements: wings upraised with 13 golden stars between them and topped by elements of a sunburst; blank shield at the eagle’s breast; arrows in its right foot and an olive branch in its left, per the U.S. seal, but with no ribbon in its mouth.

It is also the flag that Baltimore-born, college educated Christian Fleetwood hefted aloft and bore through the fight for which he received the Medal of Honor. Of the battle, he wrote:

“Early in the rush, one of the [color] sergeants went down, a bullet cutting his flag-staff. The other sergeant, Arthur B. Hilton, caught up the flag and pressed forward with them both. It was a deadly hailstorm of bullets and it was not long before [Hilton] also went down, shot through the leg. As he fell he held up the flags and shouted, ‘Boys, save the colors!’ Before they could touch the ground, Corporal Charles Veal had seized the blue [regimental] flag, and I the American flag, which had been presented to us by the patriotic women of our home in Baltimore.”

When that same flag arrived in Spicer’s workshop, she found colors overall had faded and yellowed somewhat, as evidenced by red stripes in a hidden area of the hoist, and that dark stains were scattered along the lower and fly edges. The flag’s most visible damage is the loss of its fly edge, especially the lower corner. A cascade of folds and creases had resulted from long storage wrapped around a pole. The thickness created by a second silk layer at the canton – necessary for the two painted elements – forced other layers to compensate, leading to a diagonal pattern.

Although the eagle’s paint remained firmly secured to the silk, it was marred by a number of tears, including compound L-shaped ones and a diagonal slit “affecting both the warp and weft silk threads” — meaning those that had been stationary on the loom, providing longitudinal tension, and those draw through, over and under them. Tears were limited to the painted areas, with folds on the undecorated silk of the canton.

Beyond Spicer’s typical process and procedures for conservation cleaning, repair and conservation, this project was complicated by the eventual needs for display and exhibit. “The museum felt that simply having an image [of the eagle on the reverse] was not sufficient for the importance of the flag to the community,” said Spicer. So creativity was required to balance support and visibility.

Simply sandwiching it between two pieces of glass, as had once been traditional, would place “the artifact at risk and vulnerable to damage. The smooth, hard surface of the glass did not allow for any support. In addition, areas were crushed that left long-term evidence of this type of mount as that brittle silk can no longer retain its shape. The flag or artifact was also placed at great risk if the glass broke.”

Ultimately A padded pressure mount was constructed from aluminum honeycomb with a wooden border. The majority of the flag rests on a layer of polyester needle-punched padding and pre-washed cotton fabric positioned to create a slight dome. With this pillow providing structure and support, a window could be created over the center of the eagle on the reverse.

Following its restoration, the flag became a key element of a long-term exhibit at the Maryland Center for History and Culture focused on the state’s role in and contributions to the Civil War. It closed in July 2021.

Fleetwood and the 4th USCT were part of the first, unsuccessful Union attempt to take New Market Heights. It took a fresh wave of attack and further bloody fighting before the USCT division ultimately took the position.

The 5th USCT was repulsed in its first charge and, amid that temporary retreat, Sgt. Powhatan Beaty, born into slavery near Richmond, noticed the color bearer had been killed. He returned some 600 yards under enemy fire to retrieve the flag, although this feat is not mentioned in his Medal of Honor citation. Instead, it focuses on how, with all eight of Company G’s officers casualties of the first assault, Beaty took command of the unit and led it in the second, successful attempt. All told, 91 men of the company had entered the fray, but only 16, including Beaty, survived unwounded.

After the war, Beaty — who had also seen action at the Crater, Fort Fisher and 10 other battles — returned to Ohio, where he lived before the war and where the regiment had been raised. Initially he was a cabinet maker, but the stage called and, ultimately, he became an acclaimed Shakespearean actor and playwright.

Amazingly, collections of Ohio History Connection include two flags connected to the 5th USCT, both of them on display. The National Colors flank marker can be found at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center in Wilberforce, Ohio. It is a smaller flag, of a type that was less-often saved for posterity than its larger cousins. “I suspect it wasn’t used that much,” said Cliff Eckle, a military history curator with the organization. “Its condition is almost pristine.”

At almost six-feet square, the regimental colors on display at the Ohio History Center in Columbus is much larger and more elaborate. The eagle motif is painted at the center of the blue silk, which is fringed with gold, except for the hoist.

“Due to artistic license in depicting the arms of the United States, it is likely a Cincinnati Depot flag made by Shillito’s,” Eckle said, referencing the iconic Cincinnati department store founded in 1830. “The flag must have been sent in haste because the unit designation was not painted on the red ribbon beneath the eagle.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, if it furnished a flag for Ohio’s early Black troops, Shillito’s continued to be a Civil Rights leader into the 20th century. It was the first department store chain to openly extend credit to African American customers and one of the first to open its employment ranks beyond menial jobs, offering equal pay scales and benefits. It’s flagship location in downtown Cincinnati featured the city’s first fully integrated restaurant.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

4,150

1,750