Our Fathers' War

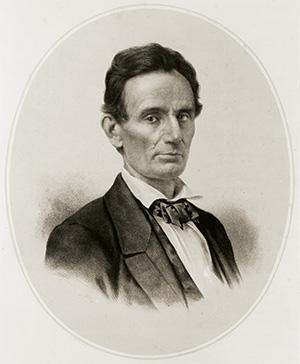

The relationship between the Civil War and the Revolutionary War was articulated by President Abraham Lincoln in the most famous sentence in American oratory: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

These words are so familiar that we rarely pause to think deeply about what Lincoln meant. The first words — four score and seven — are opaque to many Americans today, but Lincoln’s generation recognized them instantly as language of the King James Bible, signaling a message of deep and abiding importance. Lincoln chose each word with exquisite care, and built every phrase with lapidary precision. His allusions were filled with meaning that his audience understood, but that Americans of our time do not.

The first sentence of the Gettysburg Address reaches back to the Revolution, which was for Lincoln and his generation the age of America’s patriarchs. Lincoln’s audience had debated the proposition that all men are created equal. His generation knew that Thomas Jefferson and his colleagues in the Continental Congress had dedicated the nation to that proposition in the Declaration of Independence. The nation had been conceived in liberty by the people themselves, and the Revolution had been effected, as John Adams wrote, in the hearts and minds of Americans long before the first shots of the Revolutionary War were fired.

Who, then, were the fathers who brought forth the new nation?

For an answer we point quickly to the men we have learned to call the Founding Fathers, the politicians and statesmen who advocated independence and later framed the Constitution. But these were not the fathers to whom Lincoln alluded. Lincoln meant, and his listeners assumed he meant, other men. Looking for Lincoln’s true meaning we can find something of even greater importance: the vital connection between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, between the two transforming and defining events in our nation’s history.

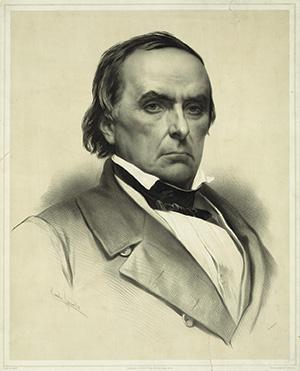

For the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln drew inspiration from his idol, Daniel Webster. Lincoln called Webster’s reply to Robert Hayne in the U.S. Senate the greatest speech ever delivered. Lincoln studied Webster’s speeches with care. One he knew better than others, because it was among the most famous American speeches of the 19th century.

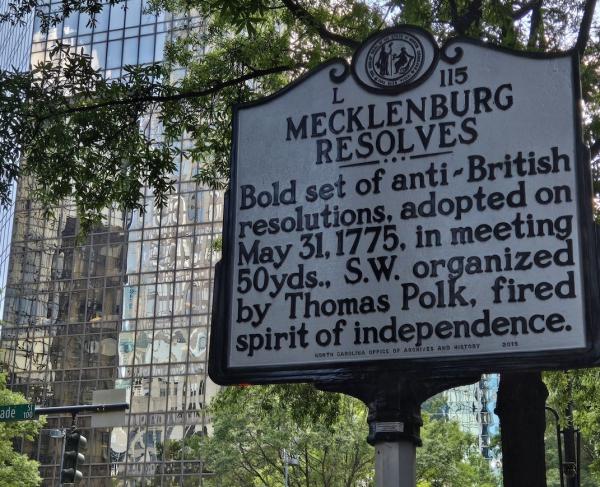

This was Webster’s oration, delivered on June 17, 1825, at the ceremony to mark the laying of the cornerstone of the Bunker Hill Monument. The story of that monument — the first great battlefield monument erected in America — is a cautionary tale for preservationists. The original Bunker Hill Monument Association was the first battlefield preservation organization in America. In the spring of 1825, the Association purchased 15 undeveloped acres on the slopes of Breeds Hill, including the heart of the battlefield of what was even then erroneously called the Battle of Bunker Hill. This was the first purchase of American battlefield land for historical purposes and included the summit of the hill where the American redoubt had stood, as well as the slopes over which the main British attack had come.

Tragically, the Association had both a limited vision about what should be preserved and limited resources. To fund the building of the proposed monument, the Association sold off the land on the slopes for development, preserving only the top of the hill for the site of the monument, which was to be a granite obelisk 221 feet high.

The cornerstone was laid on the 50th anniversary of the battle. At least 40 veterans of the battle, mostly in their 70s, were present that day. The Reverend Joseph Thaxter, wounded in the battle, served as chaplain. The Marquis de Lafayette, then on a tour of the United States, laid the cornerstone.

Daniel Webster gave the oration. By the standards of the day it was brief, though it hardly matches the lean elegance of Lincoln at Gettysburg. Yet the connection between the two speeches is clear enough, and Webster’s words are the first call to respect the hallowed ground on which Americans have fought. On that great battlefield, Webster said, “We are among the sepulchers of our fathers. We are on ground distinguished by their valor, their constancy, and the shedding of their blood.”

For Webster, of course, there was nothing metaphorical about referring to the soldiers of the Revolutionary War as fathers. His own father, Ebenezer Webster, had responded to the Lexington Alarm, participated in the Siege of Boston and fought at White Plains and Bennington. What was true for him was true for many men in the second quarter of the 19th century. Their connection to the Revolution was personal. The soldiers of the Revolutionary War were their fathers and their grandfathers.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, the memory of the soldiers of the Revolution was a constant part of public discourse. As the debate over slavery and the relations between state and nation degenerated into public discord and political violence, prudent men reminded their fellow Americans that respect for rule of law and reverence for the heroes of the Revolution — their fathers — was the foundation of American liberty.

“Let every American,” a young lawyer said in 1838, “every lover of liberty, every well wisher to his posterity, swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others. As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence . . . let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor, and let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the character of his own, and his children's liberty.”

That young lawyer was Abraham Lincoln.

For Lincoln’s generation, the Revolution was not merely the defining event in the nation’s political and constitutional history — a moment in which political theory was harnessed to political practice to establish the first constitutional republic in world history. Lincoln’s generation understood, far better than ours, that the Revolution was a traumatic event, and that its political achievement was made possible by the suffering and sacrifice of war. To us the Revolutionary War seems small — its battles mere skirmishes compared to the great battles of later wars, its death toll paltry, its suffering minor, its sacrifices modest.

Lincoln’s generation knew the truth. The political and constitutional achievement of the American Revolution stood on a foundation of sacrifice and suffering. The Revolutionary War was, until the wars of modern times, the longest war in American history. It touched every part of the new nation, from Maine to Florida, and westward to the Mississippi. It touched every community and every family. In proportion to the population, it took the lives of more Americans than every other war in our history except the Civil War, a war in which the losses of both sides are included in the total. The Revolutionary War was itself a civil war that set brother against brother and, especially in the Carolinas, degenerated into a partisan war between Americans of the sort made painfully familiar in our time in the agonies of Bosnia and the sectarian violence of Iraq.

Americans unlucky enough to be captured were crowded into rotting prison ships moored in a stagnant backwater in the East River, where their suffering prefigured Andersonville, except the prisoners packed into HMS Jersey and the other hulks listing off Brooklyn starved within site of a city where food was abundant, their miserable lives punctuated by the daily ritual, in summer’s heat and winter’s cold, of burying their dead comrades in shallow graves scooped from the stinking mud of Wallabout Bay.

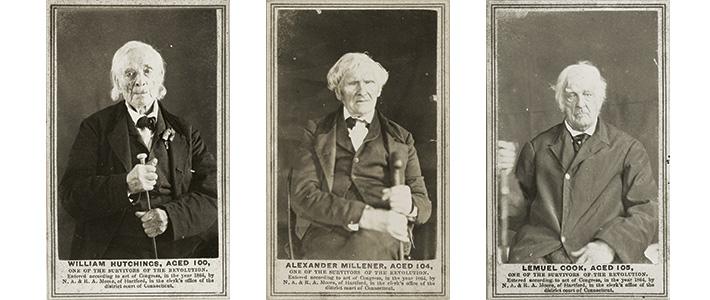

We are separated from the soldiers of the Revolutionary War by more than two centuries. They are much harder for us to imagine than the soldiers of the Civil War. They lived before photography. We have only a few portraits, most painted long after the war, to help us envision them. They left us few letters or diaries recording their battlefield experiences, describing their suffering or expressing their idealism. They were not Romantics. Unlike the soldiers of the Civil War, they contained their emotions and only rarely wrote about themselves.

Their battles are not as richly documented as those of the Civil War, which makes preserving their battlefields — where their courage, struggles and sacrifices can be imagined — vitally important. Most of their battlefields were lost to the sprawl of our cities long ago. Those that remain are hallowed ground, where men fought to establish the first nation in history dedicated to protecting the liberty and advancing the interests of ordinary people.

Lincoln’s generation understood the soldiers of the Revolutionary War much more readily than we do. “At the close of that struggle,” Lincoln said, “nearly every adult male had been a participator in … its scenes. The consequence was, that of those scenes, in the form of a husband, a father, a son or brother, a living history was to be found in every family — a history bearing the indubitable testimonies of its own authenticity, in the limbs mangled, in the scars of wounds received, in the midst of the very scenes related — a history, too, that could be read and understood alike by all, the wise and the ignorant, the learned and the unlearned.” These were the men — the soldiers of the Revolutionary War — who had brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation.

The consciousness of the Revolutionary War and its soldiers that inspired Webster and Lincoln also inspired ordinary Americans. Consider any Civil War muster roll, North or South, filled with the names of young men, the largest number of them born between 1838 and 1843. The rolls are littered with young Francis Marions — as often from north of the Ohio as south — and with Nathanael Greenes and Nathan Hales and George Washingtons, and with Jaspers and Newtons, named for Sergeant William Jasper and Sergeant John Newton, remembered as the heroic common soldiers of the Revolutionary War.

The men and women who heard Lincoln at Gettysburg understood what he meant by “our fathers.” So, too, would the men who fought for the South. “We are stel contending for houre rites,” Tennessee sergeant James Holloway wrote in June 1862, “the rites that houre fathers and grandfathers pourd out ther lives for, freedom, freedom of speache and freedom of pen and pencil.”

Confederate faith in the possibility of victory over a powerful opponent rested on the knowledge that George Washington and his army had triumphed over an enemy more powerful than the North. They endured the loss of the southern heartland and the Mississippi Valley and ultimately of Atlanta, with the knowledge that the heroes of the Revolution had lost New York, Philadelphia, Charleston and Savannah, and had triumphed all the same. As the war dragged on, the losses mounted and the suffering increased, Southerners came to idolize Robert E. Lee, the soldier whose character — whose devotion to duty, unwavering integrity, selflessness and integrity — reminded them most of Washington. The heroes of the Revolutionary War were the fathers of the South, just as surely as they were the fathers of whom Lincoln spoke.

The memory of the Revolutionary War inspired North and South, but the Civil War transformed the way Americans thought about the Revolution. The Civil War provided the nation with new heroes, with more immediate stories of heroism, of endurance and of suffering. It added new and terrible names to the roll of American battles.

The casualties in the Civil War blotted out the memory of loss in the Revolutionary War. When the Civil War began, no one imagined this would happen. Then on April 6 and 7, 1862, the armies collided in southwest Tennessee. The carnage astonished the nation. In those two days, the casualties at the Battle of Shiloh, North and South, exceeded the combined battlefield casualties of all American battles since Lexington — including the battles of the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and the Mexican War.

The nation was appalled. Horrified northerners blamed Ulysses Grant, the Union commander at Shiloh, and called for his immediate dismissal. Grant himself had hoped that one great battle would end the war. No one could have foreseen that over the next 18 months, the bloody spectacle of Shiloh would be reenacted in front of Richmond, at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Stone’s River, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and Chickamauga — and that the nation’s ordeal would become a horror beyond the scope of imagination.

The sacrifice and suffering was unprecedented. Was it all senseless? What was it for? At Gettysburg Lincoln explained: the suffering and sacrifice must lead to “a new birth of freedom” that would perpetuate the achievement and the ideals of the fathers — the soldiers of the Revolutionary War who had “brought forth” the nation. In a few words, Lincoln defined the purpose of our Revolution, paid tribute to the soldiers of the Revolutionary War and defined the purpose of the Civil War and its soldiers — living and dead — in relation to the fundamental principles for which the soldiers of the Revolution had fought and died. He made sense of the tragedy that was costing so many young lives by tying it to the sacrifice of four score and seven years before, when other young lives had been lost so that the nation might be born.

Two hundred and thirty-two years ago, our ancestors secured our independence and established the first great republic in modern history, dedicated to the liberty of ordinary people. Now the remaining battlefields of our War for Independence and the memory of that vast event are at risk. Saving them is a duty we owe to the brave men who secured our independence and the liberties we enjoy today — and to the brave men, North and South, who revered the heroes of the Revolutionary War and who emulated their courage and their patriotism.

The Revolutionary War gave meaning to the Civil War. It was the source of the ideals for which the men of North and South suffered and sacrificed, and for which so many of them gave the last full measure of their devotion.