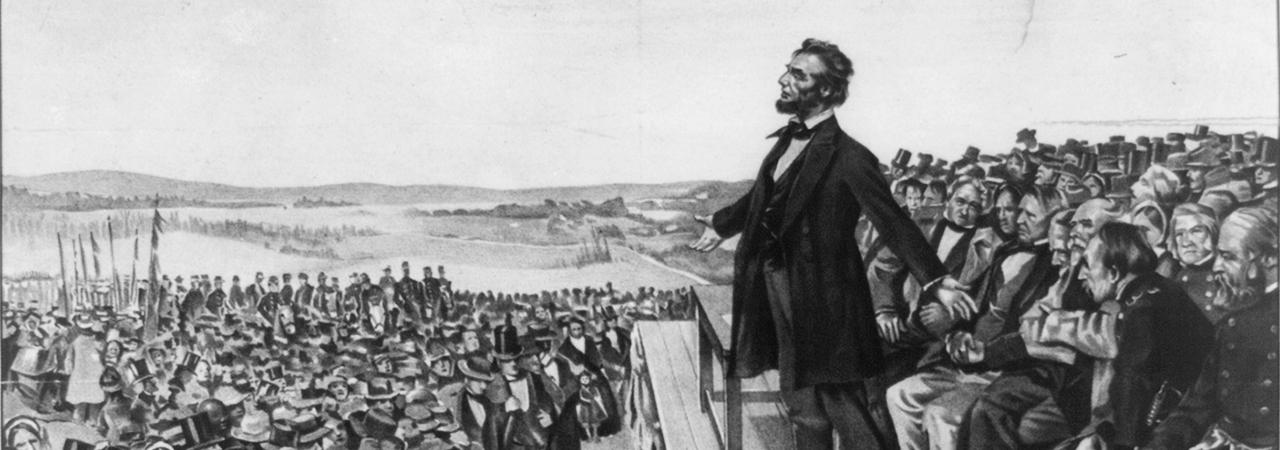

On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln uttered some of the most famous words in American history in his Gettysburg Address. The speech resulted from an invitation to the president by Gettysburg lawyer David Wills to make “a few appropriate remarks” at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg. Since then, the Gettysburg Address grew to be one of the most celebrated works of American oratory. Lincoln’s opening lines alone, “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” are perhaps only surpassed in fame by the words of the Declaration of Independence.

But which words did Lincoln utter, exactly? Five unique copies of the Gettysburg Address exist. While each of the drafts exhibit minute differences in spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and word choice, each copy retains the same basic meaning and formula. In all five copies, Lincoln begins by acknowledging the Founding Fathers and acclaims the nation’s commitment to democracy. Then, he recognizes the nation’s difficulties that lie ahead. Finally, he argues that it is the responsibility of the living to fulfill the “unfinished work” of the dead. Historians note the striking similarities between this structure and that of Pericles’s Funeral Oration during the Peloponnesian War of Ancient Greece. Lincoln perhaps drew inspiration from Pericles’s speech when he wrote the Gettysburg Address.

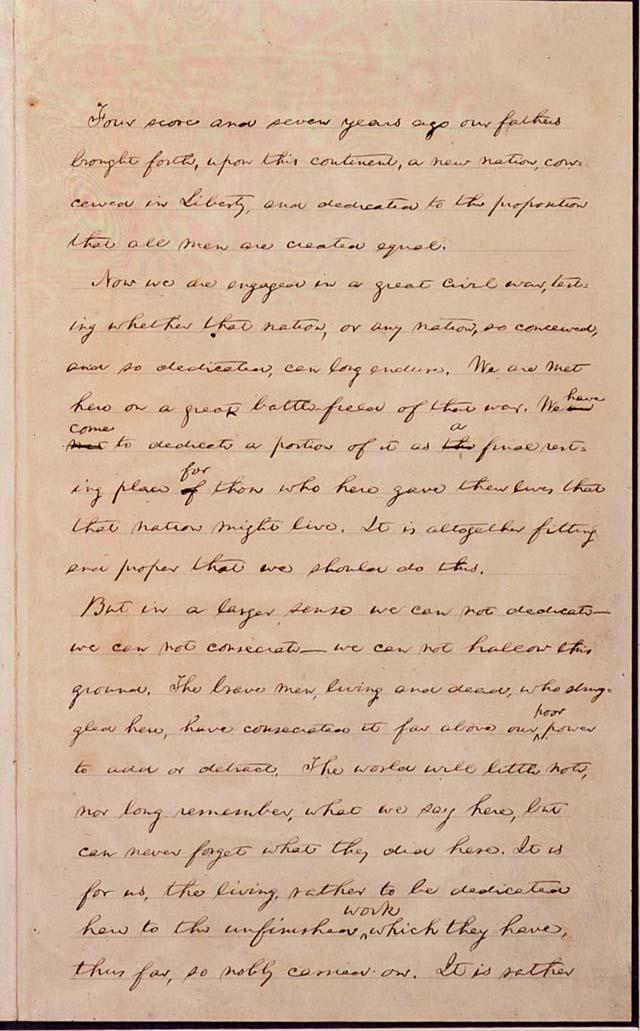

The five drafts are named after the individuals to which President Lincoln trusted each of the respective copies. The Nicolay copy is often called the “first draft” of the Gettysburg Address and is named for Lincoln’s private secretary John Nicolay. Scholars believe Lincoln wrote it either before or during his trip to Gettysburg but disagree whether it served as the president’s reading copy. Years after the war, Nicolay affirmed this copy to be the earliest in existence. It was written partially in ink on Executive Mansion stationary and partially in pencil on lined paper. Nicolay allegedly kept the draft in his possession until his death in 1901 when it passed to his friend and fellow Lincoln secretary John Hay, who received his own version of the Gettysburg Address.

The Hay copy, sometimes referred to as Lincoln’s “second draft”, differs slightly from Nicolay manuscript. It bears revisions in the president’s penmanship, probably made on the morning of the speech or on the president’s return to Washington. Some historians speculate that the president delivered this version of the address on November 19, 1863 because of its similarities to the Associated Press transcription of the speech transmitted from the dedication by reporter Joseph L. Gilbert. John Hay retained this manuscript as well as the Nicolay draft until his death in 1905. Hay’s descendants entrusted both copies to the Library of Congress in 1916.

Lincoln authored three additional copies of the Gettysburg Address following the cemetery dedication in 1863. As the ceremony’s keynote speaker Edward Everett began collecting the dedication speeches into a collection, he requested the Gettysburg Address from the president. Lincoln sent Everett a copy in 1864. Everett planned to sell the collection of speeches and donated the earnings to benefit soldiers stricken by illness.

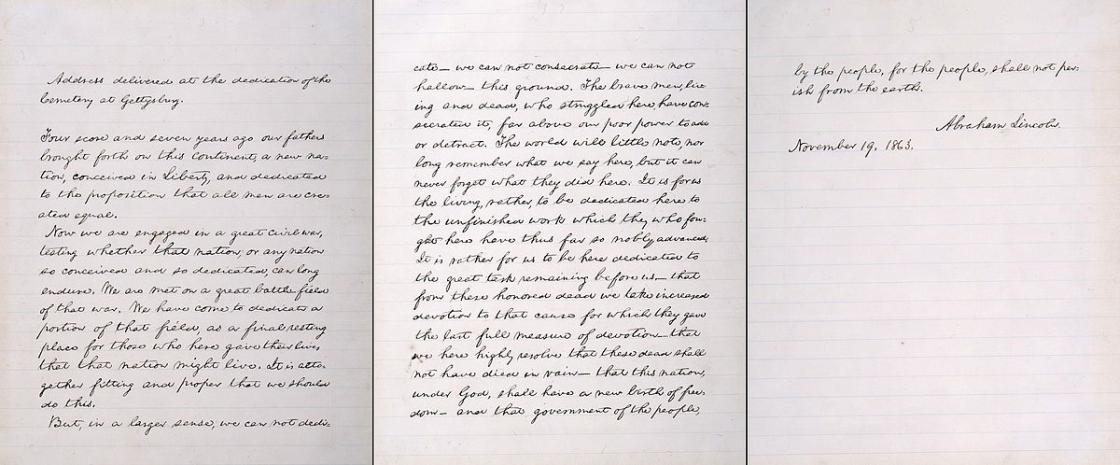

The same year, Lincoln wrote the Bancroft copy at the behest of historian and former Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft who planned to incorporate the speech in his work Autograph Leaves of Our Country’s Authors. Because the president used both sides of the paper to write this version and thus made it difficult to distribute, he permitted Bancroft to keep the copy. It remained in the Bancroft family for decades until they sold it to an individual who donated it to Cornell University in 1949. The Bancroft copy is the only draft written by Lincoln to remain in private hands. Since his fourth copy was rendered useless to Bancroft, Lincoln wrote a fifth draft known as the Bliss copy—named for Alexander Bliss, George Bancroft’s stepson and publisher of Autograph Leaves. This draft is the only one to bear Lincoln’s personal signature.

No other versions of the Gettysburg Address are known to exist. The Bliss copy quickly became the most widely distributed version, partly due to the care with which Lincoln wrote it. Former Cuban ambassador to the United States Oscar B. Cintas purchased the Bliss copy in 1949. He donated the document to the people of the United States in his will following the Cuban Revolution and specifically instructed that it be displayed in the White House. It is now displayed in the Lincoln Room of the White House and is inscribed on the south wall of the Lincoln Memorial.

While the five drafts exhibit stylistic and rhetorical variations, their grammatical and structural differences are minimal. One marked distinction between the 1863 drafts and the following copies is Lincoln’s usage of the phrase “under God.” The Hay and Nicolay copies do not contain the phrase while the three later versions do. While some scholars maintain that the president likely did not utter the words “under God” during his delivery, three correspondents at the cemetery dedication included the phrase in their telegraph reports of the speech on November 19. Other historians speculate that Lincoln deviated from his prepared script and spontaneously inserted the phrase as he spoke.

The American author Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews popularized the notion that Lincoln quickly scribbled the Gettysburg Address on the back of an envelope on his train ride to the dedication in her 1906 book The Perfect Tribute. However, the existing Nicolay and Hay copies reveal that Andrews’s tale is likely a myth. The president’s son Robert Todd Lincoln did not begin a search for the original documents until 1908, two years after Andrews published her book. His search uncovered both the Hay and Nicolay copies in the possession of John Hay, thereby debunking Andrews’s envelope story. Other erroneous myths regarding Lincoln’s authorship of the first draft arose after the war, including Harriet Beecher Stowe’s claim that the president wrote the speech “in only a few moments” and Andrew Carnegie’s assertion that he provided Lincoln with the pen.

Regardless, Lincoln's storied prose remains a hallmark of his presidency and American national identity at large. While his true words during the cemetery dedication that November day remain somewhat of a mystery, the five drafts of the Gettysburg Address reveal Lincoln's evolving thoughts and rhetorical skill. The differences of the five manuscripts do not shroud the significance of the speech nor do they obscure the president's ability to reconcile the nation's great sacrifice and meaning of the Civil War.