Peninsula Campaign

By June of 1862, following its slow advance up the Peninsula, McClellan's army was so close to Richmond Union soldiers could hear the church bells ring in the city. The end of the war seemed near at hand. But in a bold stroke, Robert E. Lee took the initiative, attacking the Union army in what would be known as the Seven Days' Battles.

During the battle of Glendale, members of Camdus Wilcox's Alabamians took Randol's Federal battery. Don Troiani's painting, Southern Cross, captures the intensity of the fighting that was typical that day.

The wounding of Confederate commander Joseph E. Johnston at Seven Pines signaled the start of a new era in Virginia — the Robert E. Lee years. Vigor replaced turpitude, aggression supplanted terminal caution. Within the first 100 hours of his regime, Lee unveiled his plan to break the Union grip on Richmond. Writing to President Jefferson Davis on June 5, Lee expressed his concerns about a passive defense. Instead, he explained, "I am preparing a line that I can hold with part of our forces in front, while with the rest I will endeavor to make a diversion to bring McClellan out. He sticks under his batteries & is working day & night." For the next three weeks, Lee concentrated his energy on executing that plan.

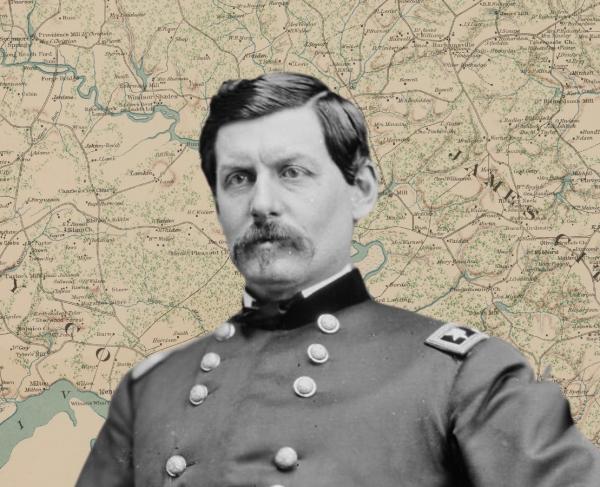

A mile or two to the east, George B. McClellan wielded the largest army in American history With nearly 125,000 men, he outnumbered Lee almost two to one. But the Army of the Potomac struggled with an immense supply line stretching from White House Landing on the Pamunkey River to the front lines nearly a dozen miles to the west, and McClellan had so positioned his five corps that the swampy Chickahominy River bisected his front. On the other hand, McClellan had momentum; he and his army had dictated the pace of events in May.

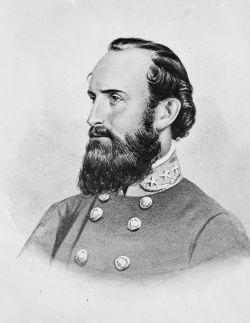

Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson proved to be the key piece in Lee's plan. After mopping up three separate Union armies in the Shenandoah Valley, the singular Stonewall pointed his 20,000-man army toward Richmond. Lee hoped that Jackson's force would be the maneuver element, sweeping in upon the Federal army's exposed upper flank northeast of Richmond. To prepare for that event Lee dispatched his chief of cavalry, Brigadier General J. E. B. Stuart, on an expedition around McClellan's right. Departing on June 12 with 1500 horsemen, Stuart rode a complete circle around the Union army, examining the approaches to McClellan's flank that would be so important when Jackson arrived two weeks later. His raid did much to prop up the morale of the South.

The real fighting began two weeks later. Historians continue to argue about the correct definition of the Seven Days' battles. The traditional interpretation has the week of battles beginning on June 25 and ending on July 1. Popular Confederate historian Clifford Dowdey argued 40 years ago that the campaign as an entity more properly began on June 26 and ended on July 2. Either way, fighting certainly began on June 25. McClellan launched a local attack that day along the Williamsburg Road just east of Richmond, his stated purpose being "to drive in the enemy's pickets from the woods." This exploded into a larger affair known variously as the Battle of King's School House, Oak Grove, or French's Farm. It ended indecisively.

The next day Lee countered with his elaborate scheme to drive off the Union army. His initial goal was to force McClellan to fight for possession of his supply line, which would entail abandonment of the lines immediately in front of Richmond. Ideally, this would lead to an open field contest away from Richmond — a circumstance infinitely more preferable to Lee than siege warfare. With Stonewall Jackson sweeping in from the northwest, Lee gathered most of his infantry on the south bank of the Chickahominy River. Jackson would clear the north bank of the river, permitting Lee to join him there and assemble a force of 60,000 troops to cut the railroad line. There were two flaws in this plan. Only 25,000 Confederates would remain in the entrenchments before Richmond (facing the bulk of the Army of the Potomac), and the success of the overall plan hinged on too much movement. It was no simple task to bring numerous columns together at a single point across miles of wooded landscape.

Lee learned this the hard way. Despite vigorous marching on the 26th, Jackson progressed slowly. Eventually division commander A. P. Hill, now recognized as one of Lee's more impetuous subordinates, crossed to the north bank of the Chickahominy River without orders, triggering the start of the Confederate plan. The Federal Fifth Corps, ably led by Brigadier General Fitz John Porter, willingly abandoned Mechanicsville in favor of a superb position behind Beaver Dam Creek. Defending two miles of front from behind entrenchments, Porter welcomed Lee's twilight attack on June 26. Although Lee recognized the folly of attempting to storm across the creek, he felt obliged (as he said after the war) to do something to divert McClellan's attention from the weakness of the stripped-down Confederate defenses, east of Richmond.

He need not have worried about McClellan. That officer determined on the night of June 26, while Porter's Fifth Corps thrashed the Confederates at Beaver Dam Creek, to abandon the supply line at White House Landing in favor of a new base on the James River. Although he inflicted 1500 casualties on the Confederate army that night, in contrast to only 300 for Porter, McClellan correctly reasoned that the arrival of Jackson above Beaver Dam Creek would signal the end of that position. Forced to either concentrate his army for a climactic fight for control of the railroad, or abandon the lines in front of Richmond altogether, McClellan took the conservative route and retreated. From that point onward the campaign consisted of the Federal army trying to save itself and its supply system from an energized Confederate army in close pursuit. June 26 decided the outcome of the campaign; the next six days would determine the extent of the Union defeat.

McClellan left the trusty Fifth Corps behind when he abandoned his railroad. Porter established a powerful position behind Boatswain's Creek, just east of Gaines Mill, on June 27. There he was to hold Lee at arm's length, buying time for the withdrawal to get started south of the Chickahominy. Lee united with Jackson's army and together they assaulted Porter's line on the afternoon of the 27th. The ensuing Battle of Gaines Mill surely was one of the fiercest of the war. Repeated assaults failed to dislodge Porter. Only when Lee combined all his troops in an enormous attack was he able to fracture the Union line just before sunset, too late to achieve a total victory. John Bell Hood and his Texas Brigade won on that field the first of their many accolades. Students of the war who are unalterably critical of frontal assaults would do well to study Gaines Mill. Unable to find a flank to get around, Lee's men instead broke three consecutive Union lines by direct attack. They incurred 9000 casualties in the process (inflicting 6000 on Porter), but they also won the first full-fledged Confederate victory in Virginia since First Manassas. Gaines Mill was Lee's largest single attack of the war, and it was his first victory.

June 28 proved to be a pivotal day. McClellan's retreat gained a head start southward because Lee could not deduce the Union army's exact intentions, and was stalled on the wrong side of the river. Once he learned of McClellan's retreat, Lee launched his pursuit. On June 29 the Federal rearguard under Edwin V "Bull" Sumner successfully repulsed a tepid attack delivered by Confederate General John B. Magruder at the Battle of Savage's Station. While Magruder and Sumner dueled, the head of McClellan's column approached the James River.

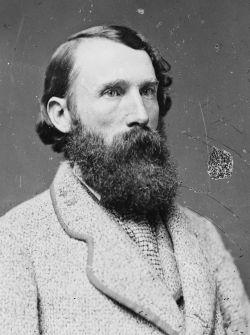

Many histories of the Seven Days identify June 30 as one of the great Confederate opportunities of the war. Confederate memoirist E. Porter Alexander wrote in an oft-quoted sentence: "Never, before or after, did the fates put such a prize within our reach." Alexander referred to the bottleneck at the Riddell's Shop intersection, more commonly called Glendale or Frayser's Farm. The better part of seven Federal divisions occupied a semi-circle around the junction of four roads. Four converging Confederate columns approached the intersection that day. Viewed on a map, it seems those Southern infantrymen had a chance to insert themselves between McClellan's army and its secure base on the James River. Three of the four Confederate columns stalled — Stonewall Jackson most unexpectedly — and the resulting battle pitted only the men of James Longstreet and A.P. Hill against several Federal divisions. In the Long Bridge Road and south of it, men grappled and ducked among long lines of Federal artillery. Waning daylight ended this fight after 7500 men had fallen killed or wounded.

Glendale ensured a successful escape for the Army of the Potomac. McClellan's divisions moved two miles farther south and established a position atop Malvern Hill, a mini-Gibraltar studded with cannon that dominated open approaches and excellent vistas. Lee saw the power of the position and did not intend to attack directly. He tried to establish an artillery crossfire to suppress the Union cannon. That ended in disaster for the Southern cannoneers, as the superior metal brought to bear by Union gunners soon silenced them. False intelligence and wishful thinking helped lure Lee into an attack anyway. Wave after wave of gray-clad infantry swept up the gentle slope of Malvern Hill to be greeted by tornadic blasts of canister and musketry. No Confederates reached the artillery, and an enormous swath of dead and dying littered the slopes. More than 8000 men fell killed and wounded at Malvern Hill, elevating the cost of the Seven Days battles to approximately 35,000 men.

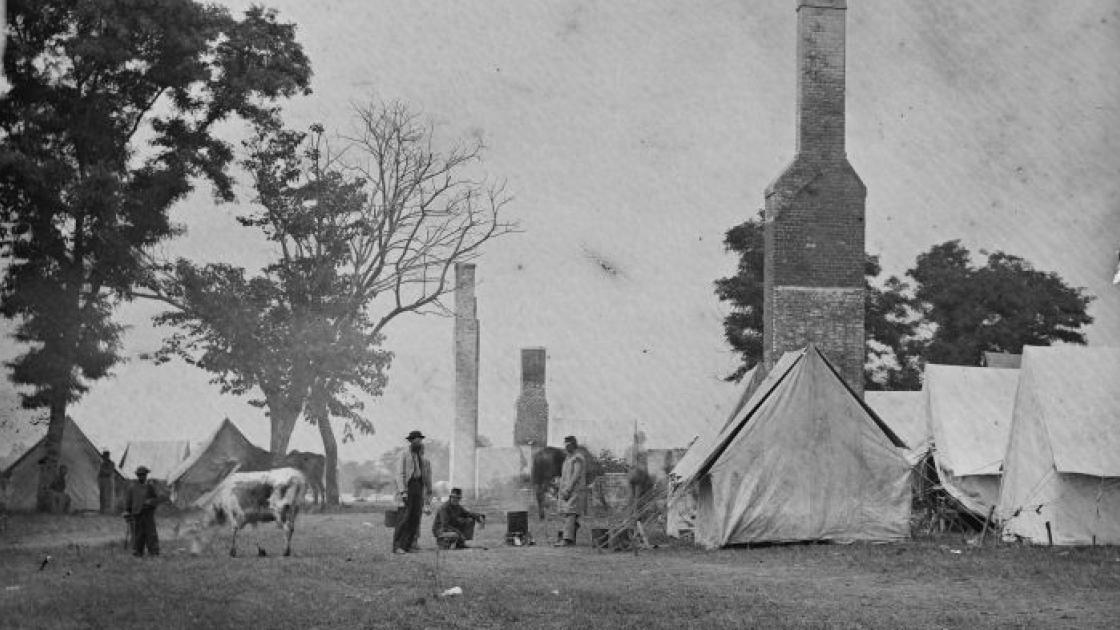

On July 2, McClellan reached his new base at Harrison's Landing on the James. Lee called off the pursuit, recognizing his inability to injure the Union army any more. The moral effect spread to the distant corners of both countries. A cheering victory that saved the capital city energized the South and gave it another hero in R. E. Lee. The Union defeat injured McClellan's standing with Lincoln, stalled the first campaign to take Richmond, and ultimately led to the evacuation of the Union army from the Richmond area. No campaign of the war before 1865 had so many consequences of such far-reaching importance.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 1999 issue Hallowed Ground, the quarterly membership magazine for the Civil War Trust.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

400

1,300