A Perfect Pandemonium

John D. Fowler, for Hallowed Ground

Although twenty years had passed, Sam Watkins, a Confederate veteran, still vividly recalled the savage struggle for Cheatham Hill, the climax of the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain and one of the bloodiest days of the Atlanta Campaign:

A solid line of blazing fire right from the muzzles of the Yankee guns . . . poured right into our very faces, singeing our hair and clothes, the hot blood of our dead and wounded spurting on us, the blinding smoke and stifling atmosphere filling our eyes and mouths, and the awful concussion [from the firing of nearby Rebel batteries] causing the blood to gush out of our noses and ears, and above all, the roar of battle, made it a perfect pandemonium. . . . When the Yankees fell back, and the firing ceased, I never saw so many broken down and exhausted men in my life. I was sick as a horse, and as wet with blood and sweat as I could be, and many of our men were vomiting with excessive fatigue, over-exhaustion, and sun stroke; our tongues were parched and cracked for water, and our faces blackened with powder and smoke, and our dead and wounded were piled indiscriminately in the trenches. There was not a single man in the company who was not wounded, or had holes shot through his hat and clothing.

Yet Watkins was just one actor in a drama that involved millions, and Kennesaw Mountain was but one battle in an epic struggle to decide the fate of two nations in the summer of 1864. That March, General Ulysses S. Grant assumed supreme command of Union armies and designed a strategy to overwhelm the weakened Confederacy with a series of simultaneous offensives. Grant’s plan involved two bold thrusts. In the Eastern Theater, Grant and the Army of the Potomac (technically still commanded by Major General George Meade) would destroy Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and capture the Confederate capital at Richmond.

Meanwhile, in the Western Theater, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman’s army group – consisting of the Army of the Cumberland under Major General George Thomas, the Army of the Tennessee under Major General James McPherson, and the Army of the Ohio under Major General John Schofield - would crush General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of the Tennessee and inflict as much damage as possible on the Confederacy’s resources. The upcoming 1864 presidential election added significance to the coming campaigns. If Abraham Lincoln lost – and there was a good chance he might – Peace Democrats proposed an armistice with the Confederacy. Although the armistice was no guarantee of Southern independence, it would stop the Federal advances and buy the beleaguered Republic time. Thus, the South’s last real hope of independence depended on stymieing the Union offensives of 1864.

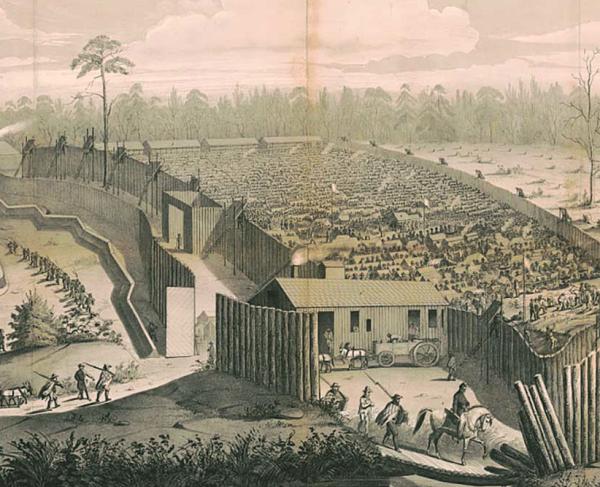

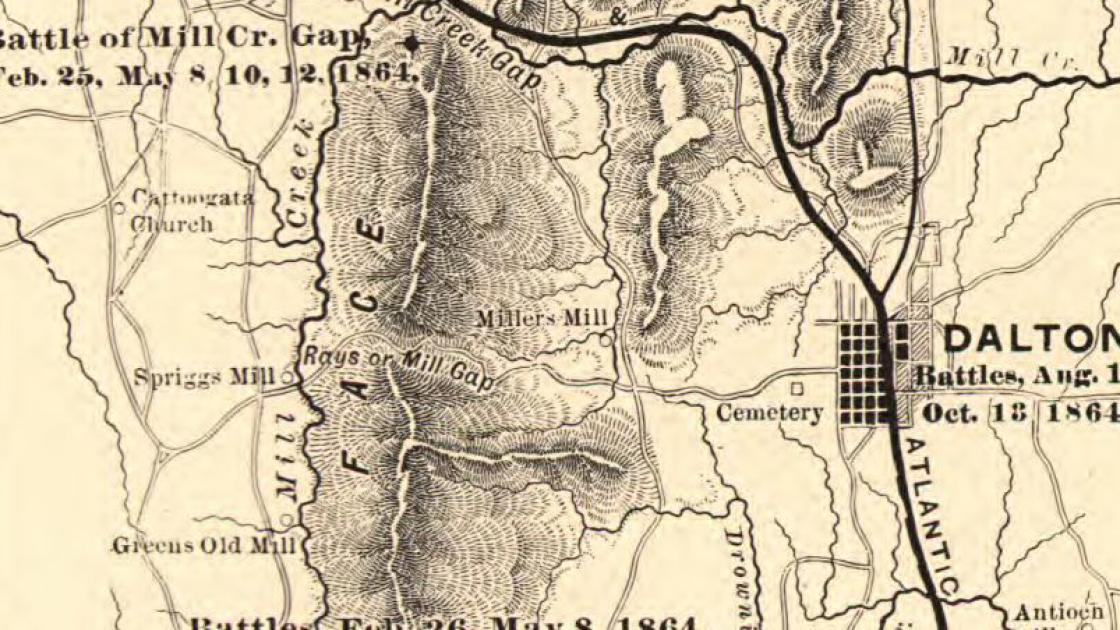

The Atlanta Campaign opened in May when Sherman put his 100,000-man force in motion toward Dalton. Johnston would have only about 60,000 with whom to face the invaders during the course of the campaign. With such a disparity, he resorted to a Fabian strategy, always entrenching his army across Sherman’s path and forcing the Federals into either a frontal assault against well prepared field works or a flanking maneuver. Johnston was ever alert for an opportunity to strike at isolated units of the Federal army but was primarily concerned with keeping his army together as a cohesive fighting force and blocking Sherman’s thrust toward Atlanta.

Starting at Dalton, the pattern of the Federals flanking entrenched Confederates continued throughout May and into June in what one historian has described as a Red Clay Minuet. As the armies maneuvered across the dense piney woods and narrow country roads of north Georgia, they clashed in a series of inconclusive battles at places such as Resaca, New Hope Church, Pickett’s Mill, and Dallas.

By late May, unrelenting rain slowed the pace of the campaign as both forces slogged along muddy rut-ridden roads. Johnston continued to invite a frontal assault; Sherman, however, refused to take the bait, and the war of maneuver continued. By the night of June 18, the Yankees had driven the Confederates back to Kennesaw Mountain, the last significant high ground before the Chattahoochee River and Atlanta. Although only 700 feet at its highest point and just over two miles long, the twin peaks of Big Kennesaw and Little Kennesaw were steep, rugged, and perfectly suited for defense. From the mountain, Confederate entrenchments extended to the right and left in a six-mile arc to the northeast and south, protecting Johnston’s lifeline – the Western and Atlantic Railroad.

At first, Sherman intended to avoid a fight at Kennesaw and sent Schofield’s Army of the Ohio to find a route around the Confederate left flank. On the 21st, Schofield crossed Noyes Creek south of the Confederate lines. Johnston quickly shifted General John Bell Hood’s corps to meet the threat. Hood, however, on his own initiative, launched an attack on the 22nd against Schofield and Joseph Hooker’s Twentieth Corps from Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland near the farm of Peter Kolb. Hood was apparently trying to pinpoint the edge of the Union line and roll up the Union flank. Alerted to the possibility of attack from recently captured Rebels, Schofield and Hooker entrenched and waited. Rebel yells announced the advance of two Rebel divisions; however, intense artillery fire and marshy terrain frustrated the Confederates, ending the Battle of Kolb’s Farm.

After Hood’s attack, almost everyone expected Sherman to continue working around the Rebel left. Sherman, however, believed Johnston had spread his forces too thin to protect his left flank, thereby weakening his center along Kennesaw Mountain. Sherman planned to exploit Johnston’s mistake with a frontal assault aimed at the Confederate center. While feints against both flanks would pin the Rebels and prevent them from reinforcing the center, General Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland would attack the Rebel line just south of Kennesaw Mountain, piercing the center and shattering the Confederate army. A secondary attack by McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee would support Thomas’s effort and divert Confederate attention.

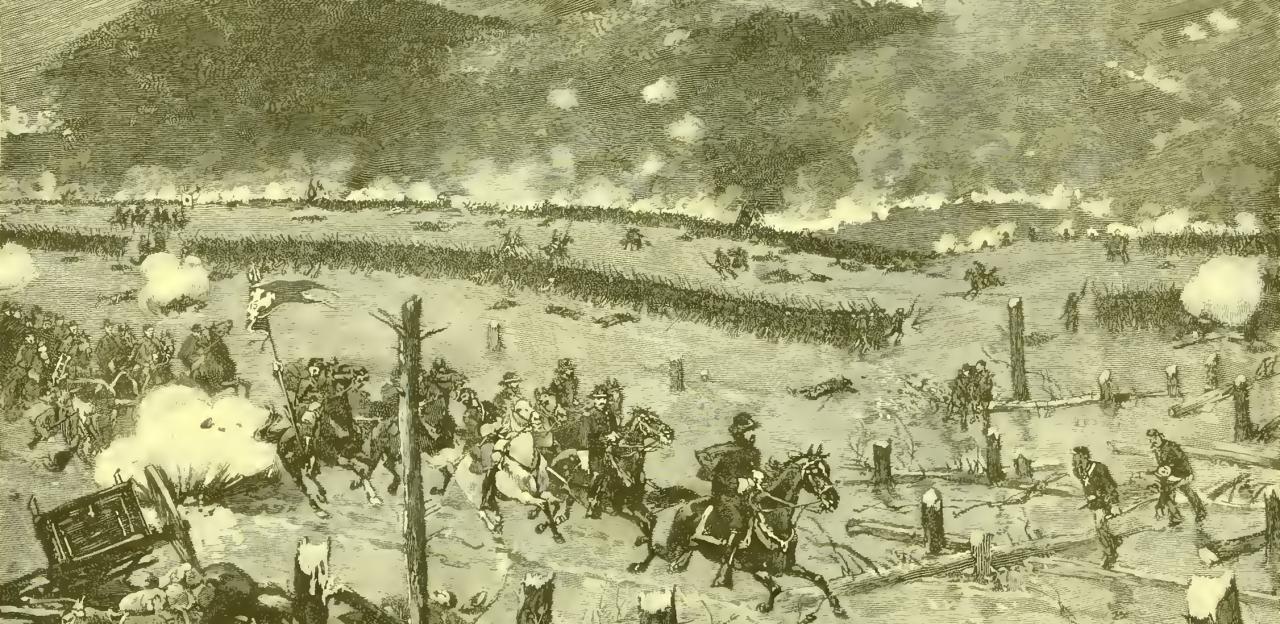

At 8 a.m. on the morning of July 27, a heavy Union cannonade heralded the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. On the Union left, General McPherson launched a feint attack at Big Kennesaw, hoping to catch the Confederates by surprise. Instead, the rocky slope and heavy fire brushed aside the assault. At the same time, farther south along the spur of Little Kennesaw (today known as Pigeon Hill), rugged terrain, coupled with Confederate fire, stalled and then repulsed the secondary Federal assault led by Brigadier General Morgan L. Smith.

Meanwhile, south of Smith’s position, the Federals launched their main assault. General Thomas had planned for two divisions to shatter the Confederate line near a salient on what is today known as Cheatham Hill (named in honor of the Tennessee general whose men held the line). Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis’s division would strike the salient head on while Brigadier General John Newton’s Division provided support to the left. Although the Union generals had planned to overwhelm the Confederate works quickly by forming dense regimental columns, such was not to be the case. As elsewhere on the battlefield, terrain, undergrowth, and Confederate fire caused command and control to collapse. Musketry decimated the compacted Yankee formation as it approached the Confederate entrenchments, and concentrated fire from previously concealed Rebel batteries sent torrents of canister ripping through their ranks. Despite this maelstrom, Union troops reached the Confederate trenches along Cheatham’s Hill at a spot that will forever be known as the "Dead Angle" and engaged the defenders in savage hand-to-hand fighting. As senior officers were killed and casualties mounted, the exhausted Federals retreated to the edge of the hill, taking shelter in a defilade, digging in, and exchanging fire with the Rebels until nightfall. In less than half an hour, the Union attackers had lost nearly 1,800 men. Although Sherman wanted to press the attack, General Thomas’s blunt assessment that “one or two more such assaults would use up this army” convinced him that further attempts to storm the Rebel works were doomed. The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain was over. It had cost Sherman about 3,000 casualties and the Confederates nearly 700.

For almost a week, both sides skirmished and waited while Union forces looked for a route around the Confederate lines. Sherman’s men slipped away to surprise Johnston on July 1, only to find the Rebels blocking their path at Smyrna. Although a tactical defeat for the Union, the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain did not seriously disrupt the relentless Federal advance. While Sherman had thus far failed to destroy Johnston’s army, strategically he still had the initiative, and, more importantly, he had the men, the materiel, and the will to continue pressing the Confederates. Only a miracle could save Atlanta and the Confederacy.