The American Revolution handed down to United States history a veritable collection of colorful characters from John Paul Jones to Benedict Arnold to Daniel Morgan, who took on mythic and legendary status in American memory after the war. Much of American memory is rooted in the narrative of great men doing heroic deeds, sometimes despite the lack of documentation. Tales about Daniel Boone, Davey Crockett, Kit Carson, and Buffalo Bill are shrouded in the American narrative. Yet we embrace them despite the shrouds because it helps to make us feel good about our national narrative.

One of the most unsung heroes of the war and the stuff of which legends are made of was the six-and-a-half-foot-tall Peter Francisco, known both as the “Virginia Giant” and the “Giant of the Revolution,” These words, attributed to George Washington, can be found on his monument is a square in downtown New Bedford, Massachusetts erected in his memory, “Without him we would have lost two crucial battles, perhaps the War, and with it our freedom. He was truly a One-Man Army.” Alas, little documentary evidence supports much of what Francisco related about his wartime experiences, including the quote attributed to Washington. Even without this documentation, he remains a compelling figure in American history, and the fact that he was honored with a commemorative postage stamp, had several monuments erected in his honor, and dates set aside in four states in his memory gives merit to some of his exploits.

Best known for supposedly wielding a six-foot broadsword, Francisco (which he most likely did not wield), a member of the Virginia Continental Line, gained mythic status at the Battle of Camden, South Carolina, where during the tumult of the collapse of the American Line Francisco spied an American cannon, mired in mud, about to be captured by the British. Surging ahead into the fray, Francisco beat off attackers and hefted the 350-pound cannon barrel on his shoulders, carrying it off the field of battle. In 1975, he was commemorated for this feat with a United States postage stamp in its Bicentennial Series, “Contributors to the Cause.” In March 1781, at the Battle of Guilford Court House, North Carolina, this American Hercules allegedly singlehandedly shaped the tide of battle, only further propelling his legendary stature. A monument at Guilford Court House National Military Park commemorates Francisco’s attests to his efforts, ”To Peter Francisco a giant in stature, might, and courage who slew in this engagement eleven of the enemy with his own broad sword rendering himself thereby perhaps the most famous Private soldier of the Revolutionary War.” During this action, he was wounded by a bayonet.

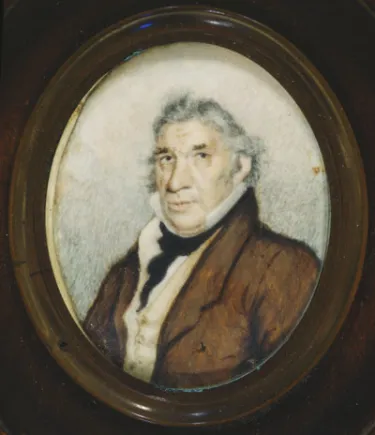

Not much is known about Francisco’s early life. He appears to have been Portuguese and raised in the Azores. Accounts vary, but according to tradition, he was indentured to a sea captain by his parents only to be abandoned at the age of five on the docks of City Point, Virginia, in 1765. As an orphan, Francisco was given shelter and minimal education by Anthony Winston of Buckingham County, Virginia, who was a cousin to Patrick Henry. In 1775, when the American Revolution began, the fifteen year-old Francisco was working as an apprentice to a blacksmith. The work suited his build and frame and gave him skills he could use in the Continental Army. In 1776, he enlisted in the 10th Virginia Regiment where he was duly noted for his size and strength.

Francisco saw action at Brandywine, Germantown, and in the desperate fighting at Fort Mifflin on the Delaware River. During these actions of the Philadelphia Campaign, he sustained wounds that laid him low for two weeks while Washington’s Army was encamped at Valley Forge. In June 1778, during the Battle of Monmouth he was severely wounded in the right thigh when a musket ball found its mark. While never fully recovering from this wound he would go on to distinguish himself in other battles. During General “Mad” Anthony Wayne’s nighttime assault on the British fortification at Stony Point, New York along the Hudson River on July 16, 1779, Francisco was in the vanguard of the forlorn hope that scaled the steep heights of the outer perimeter of the British defenders. He was allegedly the second man to burst inside the British fortification and, in the close-quarter hand-to-hand fighting that ensued, suffered a nine-inch laceration across his stomach, though contemporary sources leave Francisco's name off of the list of men who first entered the fort. Bleeding profusely, he continued to fight, supposedly capturing the British flag in the process. Though credit for the captured flag was given to a French officer. Wayne mentions Francisco’s heroics in his after action report to George Washington. The story resurfaced again when in 1820 Francisco applied for a pension from the Virginia General Assembly with a letter of support from Capt. William Evans.

After his deeds at Guilford Court House, Francisco ventured home to Virginia to recuperate from the wound he sustained there. If storming the seemingly impregnable Stony Point in the front of the forlorn hope, toting a 350-pound cannon on his broad shoulder from the midst of a battlefield, and slaying eleven redcoats with a broadsword in one battle wasn’t enough, there was more supposed adventure waiting for Francisco. Perhaps he is best known to history for “Francisco’s Fight,” an event that took place after Guilford Court House and has mythic proportions.

Francisco agreed that on his homebound journey, he would keep tabs on the troop movements of the infamous Banastre Tarleton who was wreaking havoc on American forces in Virginia with his special cavalry unit. According to his own testimony he managed to escape the clutches of Tarleton and his men not only by defeating them but getting away on one of their horses. The story goes that during the attempt by Tarleton’s men to capture the “Virginia Giant,” where they had him pinned down in a tavern, he claimed to have killed or mortally wounded at least three of eleven of Tarleton’s men. During the standoff, he came out of the tavern to face nine captors. Adding insult to injury, they ordered him to hand over the buckles of his shoes, which were made of silver. If they wanted them, Francisco said they would have to take them themselves. As they began to steal his buckles, Francisco subdued one soldier grabbing, his sword and striking him on the head. A fierce brawl broke out. In the fracas, Francisco nearly severed off the hand of the soldier whose sword he had managed to secure. Pistol shots were discharged at the hulking American, one bullet glancing off his side. Another Redcoat aimed at him with his musket only to have it misfire. In that instant, the "Virginia Giant," seized the musket from the soldier who shot at him, clutched his opponent, throwing him off his horse, and made good his getaway. Later that year, after his recovery, he was able to join Washington’s Army near Yorktown, Virginia, and witnessed Cornwallis’ surrender in October 1781.

After the war, Francisco became a popular raconteur, telling those who would listen to the dramatic tales of heroic feats he performed. He obtained a formal but basic education, attending school with children who would eagerly listen to his stories. Americans have always loved a good hero and a good story, and in the years after the American Revolution, the legend of Peter Francisco continued to evolve in American memory. Like many Revolutionary War veterans Francisco’s life was hard after the war, and he was married three times, with two wives preceding him to the grave. With his three wives, he had six children. His life eventually, as was the case with many of his revolutionary brothers, lapsed into poverty. At the end of his life, Francisco settled down near Richmond, Virginia, where he served as the Sergeant-at-Arms for the Virginia States Senate. In January 1831, at the age of 71, he died of appendicitis. He was buried with full military honors in Richmond’s Shockoe Hill Cemetery which many dignitaries attended. In his memory, the Virginia General Assembly adjourned early so that many of its members could attend the funeral.

Despite the lack of documentation about Francisco’s accolades, four states have proclaimed, March 15th, the date of the Battle of Guilford Court House, Peter Francisco Day, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Maryland, and Virginia. His memory is particularly cherished in New Bedford, Massachusetts, home to a large community of Portuguese-Americans. In this New England seafaring town at the corners of Hill and Mill Streets, one will find his monument adorned with a Sons of the American Revolution medallion of honor inside Peter Francisco Square.

Related Battles

1,310

532