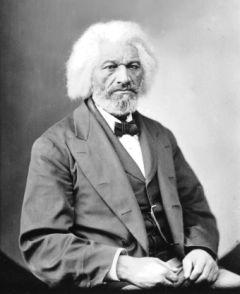

Leading abolitionist Frederick Douglass famously wrote, “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny he has earned the right to citizenship.” When the Civil War erupted in April 1861, Douglass began placing a steady stream of pressure on the Lincoln Administration to include African Americans in the Union Army. This pressure, concurrent with his pleas for immediate and uncompensated emancipation, persisted as the conflict continued. As the war raged on, the inclusion of African American soldiers in federal forces would prove both imperative to the Union war effort and to African Americans’ struggle for freedom.

Almost immediately after the start of the war, questions began to emerge regarding African Americans’ in the struggle. In August of 1861, Congress passed the First Confiscation Act, stating that all enslaved persons fighting or working for the Confederate military were freed and relieved of obligations to their masters. In July of 1862, Congress expanded this legislation with the passage of both the Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act. The Second Confiscation Act declared that the enslaved persons of Confederate civilians and military officers were to be “forever free.” However, there was a catch – this act could only be enforced in Union-occupied areas of the South. The Militia Act provided another limited step forward. The legislation allowed the president to receive African Americans into the military, but it did not clear them for combat.

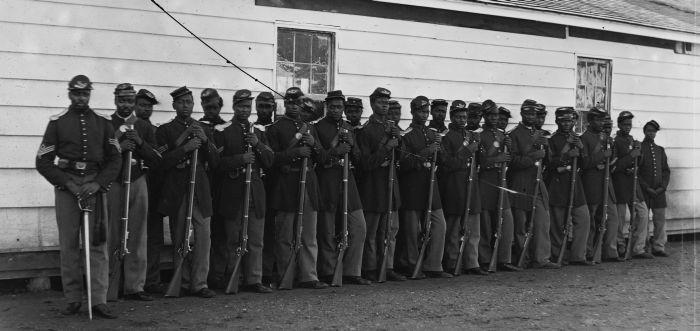

Though legislative permission was required for participation in combat, African American Union regiments were raised in places like Louisiana, South Carolina, and Kansas in the fall of 1862. The First, Second, and Third Louisiana Native Guard were organized out of New Orleans. In South Carolina, the First South Carolina Infantry included men of African descent who participated in coastal expeditions during November of 1862. Additionally, the First Kansas Colored Infantry saw service at Island Mound, Missouri, in October of 1862, before officially mustering into service. African American men serving in these early forces demonstrated their fierce passion for freedom by taking up arms and fighting for Union, even when they often received very little support from the federal government.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Not only did the proclamation establish freedom for the enslaved African Americans living in Confederate states, but it also cemented this freedom by verifying their ability to serve in the United States military. The proclamation stated that “the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons [enslaved persons], and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.” Following the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Federal government began the process of recruiting and enlisting African Americans into the official ranks of Union soldiers. For Frederick Douglass, these changes marked the reality of a long-held dream: the transformation of the Civil War from a conflict centered solely on the restoration of Union into a moral crusade for freeing the enslaved people of the South.

On May 22, 1863, the War Department issued General Order No. 143 to establish a procedure for receiving African Americans into the armed forces. The order created the Bureau of Colored Troops, which designated African American regiments as United States Colored Troops, or USCT. USCT regiments were led by white officers, and African American troops encountered little opportunity to advance within the ranks. The Bureau set out to create an ordered structure for training, drilling, and equipping large numbers of African Americans, who they feared would seek revenge on their former masters.

Initially, Lincoln was reluctant to recruit African American soldiers to take up arms against the South. However, as the war continued, his attitude shifted, particularly in the wake of continued military exigencies. As more and more African American men enlisted in the Union Army, Lincoln faced increasing pressure from white Unionists who opposed the use of colored troops. On August 26, 1863, the president penned a letter to his longtime friend, James C. Conkling of Springfield, Illinois. Knowing the letter would be made public, Lincoln wrote:

“You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then exclusively to save the Union. I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union. Whenever you shall have conquered all resistance to the Union, if I shall urge you to continue fighting, it will be an apt time, then, for you to declare you will not fight to free negroes.”

As Lincoln made clear in his letter, military necessity was a driving factor in the inclusion of African Americans in the Union Army. By the end of the war, he would come to regard their role in the conflict as crucial to Northern victory. In spite of the widespread opposition to their service, the USCT distinguished themselves valiantly on the battlefield.

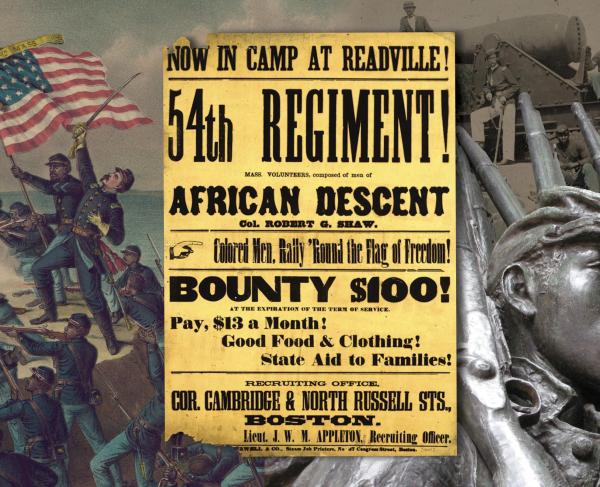

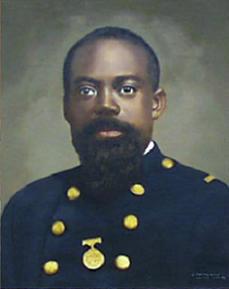

In 1989, the motion picture Glory paid tribute to the service of one such USCT regiment: the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Organized in early 1863 under the leadership of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the 54th Massachusetts was the first “officially” recruited regiment of African American soldiers. Freemen and former slaves living in the North, even as far as Canada, flocked to fill its muster roles. The 54th’s ranks were filled so quickly that another regiment, the 55th Massachusetts, was organized shortly after. On July 18, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts achieved immortality in their forlorn assault of Battery Wagner near Charleston, South Carolina. The eyes of the Union and Confederacy alike were on this singular regiment, which destroyed the persistent perception that African Americans couldn’t perform heroically in battle. In the futile assault on Confederate positions, the 54th lost more than half of its men. One of the 54th’s soldiers, Sergeant William Carney, was the first African American to win a Medal of Honor after saving the regiment’s colors. When he returned to the decimated battle line, Carney reportedly claimed, “Boys! The old flag never touched the ground.” The 54th paved the way for subsequent black regiments who continued to prove their worth at places like Big Cabin and Honey Springs, Port Hudson, Petersburg, and New Market Heights, where 14 members of the United States Colored Troops were awarded Medals of Honor.

African American soldiers continued to prove their mettle throughout the conflict, even while waging two wars at the same time: physical combat and racial bigotry. Members of the United States Colored Troops were paid less than white soldiers and were restricted from serving as officers, even in their own units. African Americans who were clergy or doctors could reach the ranks of officers, but not in combat positions. In many cases, black troops were used only for supply and guard details or manual labor. African American soldiers often faced additional dangers in the field, especially after the Confederate Congress issued a statement that any black man captured fighting against the South would be subject to immediate execution for servile insurrection, as would their white officers. In contrast to men serving on land, the United States Navy was not segregated during the Civil War. Aboard warships, African American sailors served directly alongside their white counterparts.

By the war’s conclusion in 1865, 180,000 African American men served in the Union Army, and another 19,000 served in the United States Navy. On the day that Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, there were more African American soldiers fighting for the Union than the total of all Confederate forces. More than 40,000 African American soldiers paid the ultimate price for their country, and for their journey towards self-emancipation. Abraham Lincoln credited the place of African Americans in the US Army as the tipping point in the war. Among those who served were two of Frederick Douglass’s sons, Charles and Lewis. While Lincoln saw the service of African American soldiers as crucial to turning the tides of the war, many African American soldiers saw their service as the beginning of a journey to secure their freedom in a land that promised liberty for all.