"We are happy to believe - indeed, we have very good evidence to the fact - the Administration in Washington notwithstanding appearances, stand ready to inaugurate and carry out a policy towards slavery which will most certainly eventuate in breaking down slavery in all the rebel States, just as soon as the people require it."

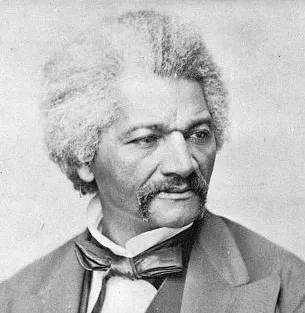

Frederick Douglass, August 1861

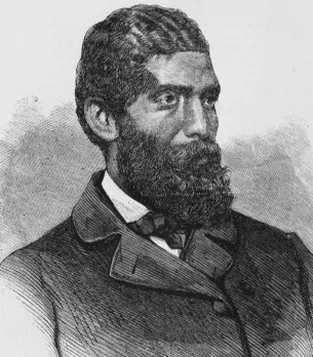

There was a profound divide in the abolitionist movement on the interpretation of the United States Constitution. William Lloyd Garrison argued that the Constitution was proslavery while James Birney argued that the Constitution was antislavery. America’s African descent abolitionists were also engaged in such a debate. In the State Convention of the Colored Citizens of Ohio held in Columbus in January 1851, African Americans debated and voted on a resolution concerning this subject. Hezekiah Ford Douglas argued that they should renounce the Constitution as proslavery because it was “a guilty compromise with Slavery in order to form the Union.” William Howard Day contended that if the Constitution “was framed to ‘establish justice,’ it, of course, is opposed to injustice; if it says plainly no person shall be deprived of ‘life, liberty, or property, without due process of law’ – I suppose it means it,” Day proclaimed, “and I shall avail myself to benefit of it.” Day argued that instead renouncing the Constitution they should work in league with the Constitution. He declared, “I consider the Constitution the foundation of American liberties, and wrapping myself in the flag of the nation, I would plant myself upon that Constitution, and using the weapons they have given me, I would appeal to the American people for the rights thus guaranteed.” At a vote of 28 to 2, the Convention resolved to work in league with the Constitution to gain equal rights as citizens and to abolish slavery.

In a New York convention held in September 1858, African descent New Yorkers stated that they regarded the Republican Party as the party “most likely than any other” to assist them in securing equity in “the elective franchise.” Identifying themselves as “Radical Abolitionists,” these New Yorkers expressed their support for the Republican Party. Like-minded African Americans across the country also expressed support for the young party. The Republican candidate in the 1856 Presidential election, the party’s first presidential candidate, John C. Fremont was publicly more anti-slavery than Abraham Lincoln the Republicans’ 1860 candidate. Fremont and his running mate William Dayton ran as the “Champions of Freedom.” African Americans believed that in spite of Lincoln’s more moderate public stance that he and his running mate, Hannibal Hamlin, were also “Champions of Freedom.” Frederick Douglass called Lincoln “a radical Republican” who was “fully committed to the doctrine of the ‘irrepressible conflict.'” New York Senator William Seward had articulated that doctrine as a conflict between slavery and freedom which the nation's founders intended freedom to win.

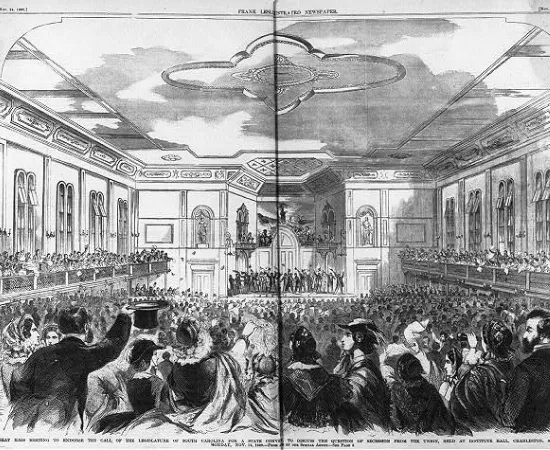

Many Southerners shared Douglass’s opinion of Lincoln. This opinion of Lincoln and his party exacerbated regional tensions fostered by slavery. Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1820 that such tensions established along “a geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political,” especially as it pertained to the disposition of new territories as either slave or free, would lead regional leaders to an “act of suicide on themselves and of treason against the hopes of the world.” On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union declaring: “A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the states north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.” Like the secessionists of South Carolina, many African Americans believed that Lincoln’s Republican administration would seek to abolish slavery throughout the republic. Douglass wrote that in Lincoln the nation had elected, “if not an Abolitionists, at least an anti-slavery reputation to the Presidency of the United States.” Lincoln, the secessionist declared, was “entrusted with the administration of the common Government, because he has declared that ‘Government cannot endure permanently half slave, half free,’ and that the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction.” Indeed what South Carolina’s secessionists asserted in their “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union” as the goal of Lincoln’s party was what African Americans hoped was the ultimate objective of the Republican Party, to make the Republic all free.

The 1860 Republican platform was an anti-slavery platform. Declaration number 8 read: “That the normal condition of all the territory of the United States is that of freedom; that as our republican fathers, when they had abolished slavery in all our national territory, ordained that no ‘person should be deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law,’ it becomes our duty, by legislation, whenever such legislation is necessary, to maintain this provision of the constitution against all attempts to violate it; and we deny the authority of congress, of a territorial legislature, or of any individuals, to give legal existence to slavery in any territory of the United States.” This declaration was a direct assault on the Kansas-Nebraska Act which left the decision of whether a territory would allow slavery within its borders to the voters of that territory. The declaration also stated clearly that the Republicans viewed it as their duty “by legislation” to ensure that “no ‘person should be deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law,’” not by executive order but “by legislation.” Southern secessionists were concerned about the Republican President-elect and the Republicans in Congress.

Congress was not in session when open hostilities began on April 12, 1861, with the firing on Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. President Lincoln responded to the national emergency by issuing a proclamation calling for a special secession of Congress to convene on July 4, 1861. In his proclamation, Lincoln also called for 75,000 volunteers from the states “in order to suppress said combinations,” which meant suppress the newly formed Confederate States of America. Maryland was the only slaveholding state that promised troops. Kentucky refused to send volunteers declaring, “Your dispatch is received. In answer, I say emphatically that Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern States.” Missouri’s governor claimed that the call for volunteers was “illegal, unconstitutional, and revolutionary.” He declared, “Not one man will, of the State of Missouri, furnish or carry on such an unholy crusade.” However, the Northern response was enthusiastic with Pennsylvania promising “100,000 men if necessary.” Harper’s Weekly pronounced Lincoln’s proclamation to be “an absolute declaration of war,” and thousands of volunteers were mobilized within a week after Lincoln’s call for volunteers.

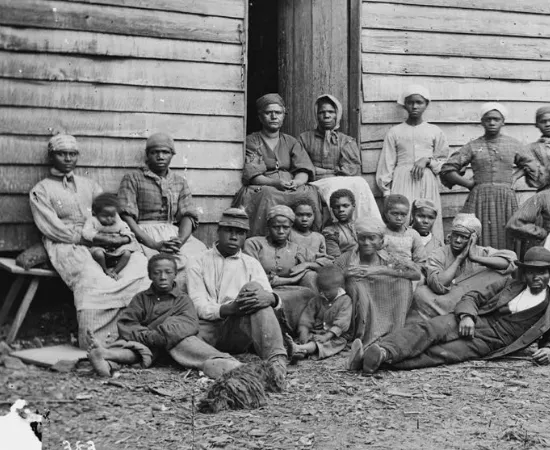

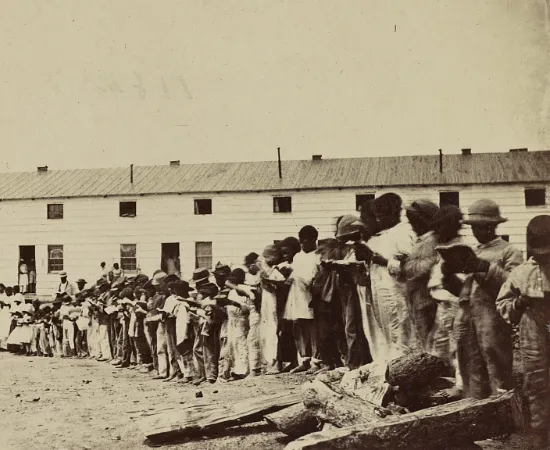

Men of African descent were eager to answer Lincoln’s call for volunteers. There were nearly four million Americans of African descent held for their labor, held as slaves, when the war began. There were a half million free persons of African descent in the United States with approximately an equal number residing in the North and in the South. Free and enslaved they could not answer Lincoln’s call for volunteers because it was not legal for them to join the Federal militia, and not a single Northern state permitted them to join its state militia. In spite of this prohibition, a small number of African Americans answered the call for volunteers anyway. Nicholas Biddle was not officially enlisted in the Pennsylvania state militia; yet, he served as the orderly for Captain James Wren of the Pennsylvania Volunteers’ Washington Artillerists. Biddle was struck by a brick on April 18, 1861 while he marched with the battery down Pratt Street in Baltimore, Maryland. In Connecticut, William Henry Johnson enlisted in the 2nd Connecticut Infantry in 1861 as “an independent man” after being denied enlistment as a “Negro.” Johnson fought with his regiment at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. Eight days after the call for volunteers, Jacob Dodson an African descent employee at the U. S. Senate building informed Secretary of War Simon Cameron that he knew three hundred free men of color in Washington “who desire to enter the service for the defence [sic] of the city.” Their services were rejected.

Allan Pinkerton, the head of Union intelligence gathering under General George McClellan wrote, “Although as yet prevented from taking up arms in defense of their rights, these colored men had banded themselves together to further the cause of freedom, to succor the escaping slave, and to furnish information to loyal commanders of the movements of the rebels.” Pinkerton reported that these Americans had established a national organization called the Loyal League, a secret organization established in anticipation of the war. Like Jefferson, the Loyal League believed that regional tensions fostered by slavery would lead to a civil war. John S. Rock, an African American physician, dentist, teacher and lawyer conveyed such an understanding on March 5, 1858, over three years before the war began. “Sooner or later the clashing of arms will be heard in this country,” Rock said, “and the black man’s services will be needed: 150,000 freemen capable of bearing arms, and not all cowards and fools, and three quarter a million slaves, wild with the enthusiasm caused by the dawn of the glorious opportunity of being able to strike a genuine blow for freedom, will be a power which the white man will be ‘bound to respect.’ Will the blacks fight? Of course they will.”

When “the clashing of arms” was heard, the Federal government did not have a policy concerning the military employment of persons of African descent. Some state and federal officials simply declared that the war was “a white man’s war” and rejected their offers of assistance. The Confederacy, however, contracted with slaveholders for the use of their slaves as laborers and impressed free men of color into labor as well. Slave labor was critical to the Rebel war effort, and thousands of African Americans were impressed to labor in support of the Confederate army and navy. This labor imperative also provided an opportunity for Southern members of the Loyal League to infiltrate the Confederate military. Pinkerton reported, “I found that my best source of information was the colored men, who were employed in various capacities of military nature which entailed hard labor.”

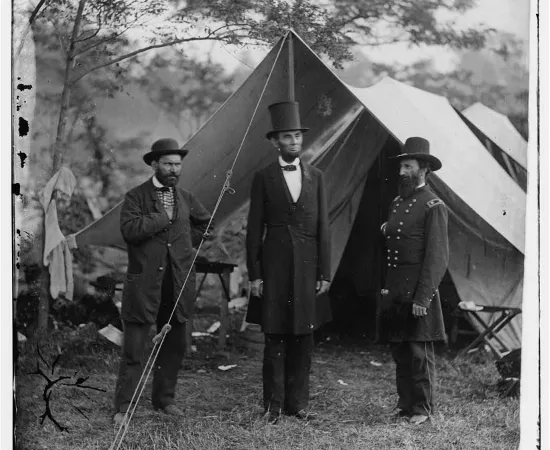

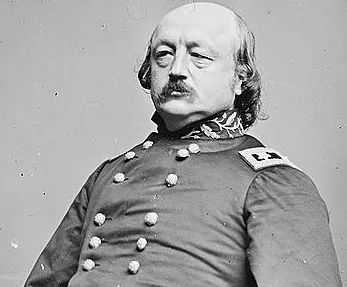

General Benjamin F. Butler established the protocol on how to deal with enslaved persons used for military purposes by the Rebels. Butler was not a well-trained military officer, but he was the Union’s first strategically significant military hero. General Lafayette Baker the head of the National Police that provided security for the District of Columbia wrote of Butler: “Whatever maybe the estimate put upon the military status of Benjamin F. Butler to his energy, courage, and executive power in an emergency, the country is indebted for the position of Maryland during the war.” With crucial information on secessionist activities in Maryland, Butler thwarted attempts to bring Maryland into the secessionist fold and marched his troops into Baltimore in early May 1861 arresting the leading secessionists there. President Lincoln lifted the writ of habeas corpus in order to protect the spies who informed Butler. This was a very controversial action by the President because the authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, the right to be brought before the court with evidence presented to justify detention, was specially granted to the legislative branch in Article I: Section 9: paragraph 2 of the U. S. Constitution “in cases of Rebellion or Invasion.” Lincoln promoted Butler to major general after his success in Maryland and reassigned him to command Union forces at Fortress Monroe on the Virginia Peninsula, where he would establish the protocol on how to deal with enslaved persons forced to labor for the Confederacy.

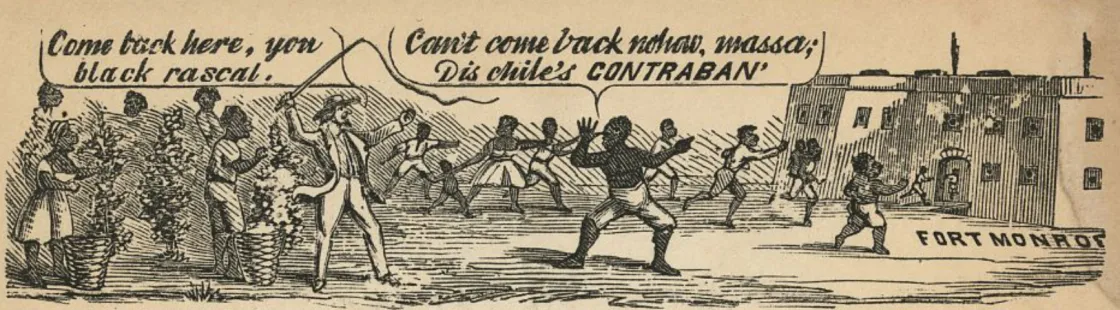

After being forced to work on Rebel fortifications along the Virginia Peninsula, three enslaved men (Frank Baker, James Townsend and Sheppard Mallory) came into Fortress Monroe seeking refuge on May 23, 1861, the day Virginia voters voted to secede from the Union and the day after Butler took command of the fort. Butler opportunely provided them a sanctuary, and the next day a Rebel officer met with Butler under a flag of truce and appealed to him to return the three men in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act, which required all officers of the Federal government to assist slaveholders in capturing and returning fugitive slaves. “But you say you have seceded,” Butler argued, “so you cannot consistently claim them. I shall hold these negroes as contraband of war [emphasis added], since they are engaged in the construction of your battery and are claimed as your property. The question is simply whether they shall be used for or against the Government of the United States.” Butler an experienced attorney appreciated the legal opportunity presented to him, and his argument was enthusiastically supported by Secretary of War Simon Cameron. Fortress Monroe quickly became a refuge for hundreds of enslaved persons who had been employed for military purposes by the Rebels.

The question of whether enslaved persons would “be used for or against the Government of the United States” was one of the most important concerns to be addressed in the special session of the 37th Congress that convened on July 4, 1861. But the first order of business was to draft a resolution stating clearly the object of the war. The resolution drafted in the Senate was authored by a slaveholding Democrat from Tennessee, Andrew Johnson. Senator Johnson decided to remain in the Senate after Tennessee had seceded from the Union. The author of the resolution in the House was a former senator from Kentucky, Representative John J. Crittenden. The “Object of the War” pronounced in the joint resolution, authored by non-Republicans from slaveholding states, was “to maintain the supremacy of the Constitution and to preserve the Union and not to overthrow or interfere with the institutions of the states,” and the “peculiar institution” of slavery was the institution of concern. President Lincoln affirmed this resolution. The paramount objective was to preserve the Union, and around that object the nation was called to rally. Debates on emancipation were avoided in that special session. The war was officially being fought to save the Union and not to end slavery.

Though introduced eleven days into the special session, legislation addressing how to deal with enslaved persons being used “against the Government of the United States” did not come to a vote until the end of the special session in early August. Senator Lyman Trumbull a Republican from Illinois introduced a bill on July 15, 1861 “to confiscate property used for insurrectionary purposes.” There were reports in the newspapers and rumors circulating in Congress that the Rebels were using their slaves as soldiers. After the First Battle of Bull Run, Trumbull made such an allegation: “I understand that negroes were in the fight that recently occurred. I take it that negroes who are used to destroy the Union, and shoot down the Union men with the consent of traitorous masters, ought not to have them restored to them.” Some congressmen believed that such confiscation of property was a pretext to emancipation. Crittenden declared, “You cannot make a general law that regulates slavery that shall regulate the rights of masters or the rights of the servant in a State in this Union, in time of peace… Now I ask my friend is this bill not getting around that, making use of the state of war, of a state of things that highly excites us all?” Representative William Kellogg a Republican from Illinois sought to allay the concerns of those in opposition to emancipation. “I have endeavored by my amendment so to modify the bill,” said Kellogg, “that shall be understood by the country as not affecting the institution of slavery in the States.” The legislation known as the First Confiscation Act was signed by President Lincoln on August 6, 1861. According to the act, those to be “confiscated as contraband of war” were only those persons working or employed “in or upon any fort, navy yard, dock, armory, ship, entrenchment, or in any military or naval service whatsoever, against the Government and lawful authority of the United States.”

Though some government officials inferred that the “contrabands” were freed by this act, emancipation was not expressly granted by it. The act simply stated that “the person to whom such labor or service is claimed to be due shall forfeit his claim to such labor.” When Congress adjourned in August 1861, the persons “confiscated” under the provisions of this act were in a sort of legal limbo. They were confiscated property “contrabands” not freedmen. Harper’s Weekly broached this quandary in an August 24, 1861 article entitled “Slavery and the War” reporting “to what extent the confiscating Act of Congress may be applied to slaves; and what other accidents may befall the institution in the course of the war – no one, of course, can guess.” The paramount object was to preserve the Union, and slavery would be dealt with in accordance with that objective.

Frederick Douglass wrote in August 1861 that he had “very good evidence to the fact” the Lincoln administration, “notwithstanding appearances,” stood ready to enforce a policy in the rebellious states that would eventually abolish slavery in those rebellious states “just as soon as the people require it.” The voice of the people in the Federal government is expressed through the legislative branch, Congress. In this article, Douglass evinces that he understood that by legislation the Lincoln administration would seek to attack slavery where it already existed. Clearly, the Republican platform had stated that “by legislation” the Lincoln administration would address the issue of slavery in the territories. However, Lincoln’s commitment to the legislative process made him appear almost conciliatory on the slavery issue and far more moderate than other leading Republicans like John C. Fremont.

On August 30, 1861, General John C. Fremont demonstrated just how radical the former Republican candidate for president was. As the commander of the Department of Missouri, Fremont proclaimed martial law in his department and declared free slaves in Missouri. Lincoln ordered Fremont to modify his order to conform to the First Confiscation Act. Fremont requested that Lincoln publicly modify the general’s proclamation. Lincoln replied in an open letter dated September 11, 1861. Lincoln stated that he had no objection to Fremont’s proclamation except for the clause “in relation to the confiscation of property and the liberation of slaves.” Lincoln explained that he found the clause “to be objectionable in its non-conformity to the act of Congress.” Lincoln wrote, “It is therefore ordered that the said clause of said proclamation be so modified, held, and construed as to conform with and not to transcend the provisions on the same subject contained in the act of Congress entitled 'An act to confiscate property used for insurrectionary purposes' approved August 6, 1861.” While giving the appearance of not supporting emancipation, Lincoln clearly stated that Fremont had gone beyond the legal authority Congress had granted the Chief Executive. According to Frederick Douglass, he had evidence, “notwithstanding appearances,” that Lincoln stood ready to enforce a policy of emancipation in the Rebel states “just as soon as the people require it,” which means when Congress provided the appropriate legislation. Fremont had acted ahead of Congress.

In early 1862, many leading abolitionists were growing impatient with an administration that did not appear to be supporting emancipation. However, leading African American abolitionists defended the President. “While Mr. Lincoln has been more conservative than I had hoped to find him,” John S. Rock said, “I recognize in him an honest man, striving to redeem the country from the degradation and shame into which Mr. Buchanan and his predecessors have plunged it.” In a speech delivered on January 23, 1862 to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, Rock expressed his confidence in Lincoln and argued that emancipation was a military necessity and that the government would come to realize that fact. “This rebellion for slavery means something!” Rock declared. “Out of it emancipation must spring.” Rock believed that the time was rapidly approaching when the government in Washington would understand that to ensure its very existence it must “take slavery by the throat, and sooner or later must choke her to death.” Rock expressed the aspirations and intentions of those African Americans who “had banded themselves together to further the cause of freedom” when he declared, “we are now prepared to attack the enemy.” Indeed, African Americans believed Lincoln was leading the nation in that direction, toward emancipation ordained by legislation.

President Lincoln sent a message to Congress on March 6, 1862 encouraging Congress “to co-operate with any State which may adopt gradual abolishment of Slavery, giving State pecuniary aid, to be used by such State in its discretion, to compensate for the inconveniences, public and private, produced by such change of system.” While some abolitionists criticized Lincoln for offering compensation to slaveholders, others accused the President of trying to form an abolition party in their states by offering inducements. In a meeting with Border State congressmen on March 10, 1862, President Lincoln was asked by Representative William A. Hall of Kentucky his opinion regarding slavery. The congressmen present reported that Lincoln said “he did not pretend to disguise his anti-slavery feeling; that he thought it was wrong, and should continue to think so.” According to the Border State congressmen, Lincoln clearly stated his displeasure in having to protect the right to hold other persons as property and that such a law was to him an “odious law.” He told them “he would get rid of the odious law, not by violating the rights [to this type of property], but by encouraging the proposition and offering inducements to give it up.” Lincoln was actively pursuing a legislative course, propositions along with inducements, to abolish slavery.

Consistent with Lincoln’s incentives to abolish slavery, Senator Henry Wilson, the junior senator from Massachusetts, introduced a bill in Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for the lost property. As a member of the House of Representative in January 1849, Lincoln had drafted such a bill, but he never introduced it. In April 1862, Congress passed Wilson’s bill emancipating the enslaved in the District of Columbia and compensating the slaveholders up to $300 for the property forfeited. Declaring that he always thought Congress had the authority to abolish slavery in the District; President Lincoln signed the Immediate Compensated Emancipation Act into law on April 16, 1862, emancipating 3,104 persons in the District immediately. Senator Charles Sumner, the senior senator from Massachusetts, called it “the first installment of the great debt which we owe to an enslaved race, and will be recognized as one of the victories of humanity.” What would be the second installment?

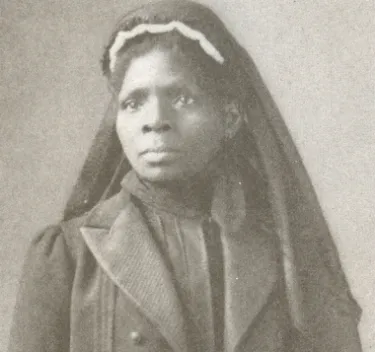

The military situation by the late spring of 1862 gave Union supporters reason to be confident that victory could be achieved within the year. The Union Army and Navy had gained control of New Orleans, Memphis, and Nashville as well as the Sea Islands of South Carolina and the major cities and forts of Northeastern North Carolina that spring. Also General George McClellan had assembled arguably the best trained and best equipped army in the world. McClellan’s army was certainly the largest army in the Western Hemisphere. He trained his army in the Washington area. After some prodding from the President, McClellan sailed his army down to the Virginia Peninsula. McClellan marched the largest army in the Western Hemisphere up the Virginia Peninsula to within ten miles of Richmond the Rebel capital by June 1, 1862. Some abolitionists feared there would be no more “installments” if McClellan captured Richmond. When word of McClellan’s apparent success reached the contraband camp at Hilton Head, South Carolina, a resident of the camp Susie King Taylor reported “we were told that there was going to be a settlement of the war… It was a gloomy time for us all.” Members of the Loyal League “had banded themselves together to further the cause of freedom,” and they wanted emancipation to become a military necessity. They believed that “out of [the rebellion] emancipation must spring,” but McClellan’s early success in his Peninsula Campaign cast doubt on that possibility. Therefore, African descent spies working with Pinkerton furnishing “information to loyal commanders of the movements of the rebels” certainly understood that for emancipation to become a military necessity, McClellan had to fail.

On the same day that McClellan’s army occupied positions within ten miles of Richmond (June 1, 1862), General Robert E. Lee took command of the Confederate forces in the defense of the city. Lee’s army was less than half the size of McClellan’s army, but Lee was able to deceive McClellan into believing that his army was four times its actual size. Earlier that spring, Pinkerton had lost his top operatives in Richmond. Timothy Webster and Hattie Lawton were arrested by Confederate authorities in the city, and Webster was subsequently convicted and hung for being a Federal spy. Pinkerton, therefore McClellan, was heavily dependent on African American informants. Pinkerton’s reports inflated the size of the Confederate forces, and Lee was able to deceive McClellan into believing that wooden canons, called “Quaker Guns”, were real canons. While engaged in some of the fiercest fighting of the war to that date and believing that he was outnumbered, McClellan appealed to Washington for more troops. As McClellan’s army gave ground to Lee’s numerically inferior army, Congress passed and President Lincoln signed into law the “second installment” on June 19, 1862, the Territorial Abolition Act, which abolished slavery in all Federal territories. Congress was also debating a more comprehensive confiscation act that included emancipation. In the first week of July, Washington steadfastly refused to supply McClellan with more troops in spite of his consistent appeals. After word got to Washington that McClellan’s army, the largest army in the Western hemisphere, was in full retreat suffering a humiliating defeat, Congress passed a “third installment,” the Second Confiscation Act.

At least one senator believed that emancipation had become a military necessity by design. On June 24, 1862, Senator Willard Saulsbury, Sr. a Democrat from Delaware directing his comments to the Republicans in the Senate declared, “Your design is to make this a war for the abolition of slavery.” He then proceeded to list what he considered to be abolitionist related propositions and legislation brought forward by the Republicans in the 37th Congress: 1) “You have abolished slavery in the District of Columbia without the consent of their owners and against their wishes.” 2) “You have made it an offense punishable by dismissal from service for any officer of the Army to return a fugitive slave to his loyal owner…” 3) “You have, upon recommendation of the President, attempted to build up an abolition party in the border slave States by the offer of pecuniary aid…” 4) “You have prohibited slavery, not only in existing territory but in any which may hereafter be acquired…” and 5) “You have by your bills proposed the emancipation of almost the entire slave population in the States, and now the bill before the Senate is to be amended, if possible to accomplish that object.” This amended bill, “the third installment,” would become the legislative or simply the legal basis of the Emancipation Proclamation. By this legislation, the war to preserve the Union became a war for emancipation. In Saulsbury’s opinion this had been by design.

Two pieces of legislation pertaining to persons of African descent were presented to President Lincoln on July 17, 1862. The Militia Act of 1862 gave the President the authority to employ “persons of African descent” in any military capacity for which he saw fit. The act known as the Second Confiscation Act gave clear incentive to enslaved persons to assist the Union war effort as it transformed the war into a war for emancipation. In section 9 of the act, Congress declared all persons held as slaves by supporters of the rebellion forever free. After signing both of these acts yielded by military necessity into law, the President had the legal authority to arm men of African descent and to declare free slaves in states in rebellion. By legislation, the war had become a war for emancipation. Senator Charles Sumner declared that the passing of this legislation was “an occasion of just congratulation that the long debates of this session have at last ripened into a measure which I do not hesitate to declare as more important than any victory which has been achieved by our arms. Thank God!” The road to emancipation had been paved by legislation.

On the day President Lincoln signed the Second Confiscation Act (July 17, 1862), thousands of enslaved persons in contraband camps from Washington to New Orleans were not simply confiscated property, contraband, anymore--they were forever free. They were freedmen. While African descent infantry regiments were being organized among those emancipated by the act of Congress, Lincoln was being criticized for not issuing a proclamation of emancipation. However, his reasoning for not issuing a proclamation immediately was based on sound political advice. On July 22, 1862, five days after signing the Second Confiscation Act, he met with his cabinet and informed them that he was going to issue an emancipation proclamation acting on the authority that Congress had granted him. He gave a draft of his proclamation to his cabinet members and asked for their advice. Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase recommended that the President add stronger language to his proclamation concerning the arming of men of African descent. Another of Lincoln’s cabinet members Secretary of State William Seward advised the President not to issue his proclamation at that time, in July 1862. Seward was an abolitionist who had supported operations along the Underground Railroad, yet he advised Lincoln not to issue the Emancipation Proclamation in July 1862. Why?

Congressional elections were coming up, and Seward was concerned about how the voters might interpret such a proclamation on the heels of the humiliation suffered by McClellan’s army during the Peninsula Campaign. Seward told the President, “It will be viewed in the mind of the people as the last measure of an exhausted government, a cry for help; the government stretching forth its hands unto Ethiopia instead of Ethiopia stretching forth her hands unto the government.” (Ethiopia was commonly used to refer to African Americans in the 19th Century.) Seward advised Lincoln to wait until he could “give it to the country supported by a military success, instead of issuing it, as it would be the case now, upon the greatest disasters of the war!” Lincoln said he viewed “the matter as a practical War measure, to be decided on according to the advantages or disadvantages it may offer to the suppression of the Rebellion.” Thus, considering Seward’s advice wise political advice, Lincoln decided to wait for a military success that would mask the government’s cry for help to African Americans. Yet, many abolitionists wanted Lincoln to issue an emancipating proclamation and did weigh not the practical political reality necessitating a Republican majority in the Congress. To them it simply appeared that Lincoln was appeasing slaveholders by not acting on the authority the recent acts of Congress had granted him.

While Lincoln waited for a military success to support his Emancipation Proclamation, Horace Greely publicly criticized the President for the policy Lincoln seemed to be pursing. “We think,” Greely wrote, “you are strangely and disastrously remiss in the discharge of your official and imperative duty with regard to the emancipating provisions of the new Confiscation Act. Those provisions were designed to fight Slavery with Liberty.” In Greely’s article entitled “The Prayer of the Twenty Millions”, which appeared in the New York Tribune on August 19, 1862, he appealed to the President “to render a hearty and unequivocal obedience to the law of the land.” In accordance with the “new Confiscation Act,” the law of the land was that all persons held as slaves by supporters of the rebellion were forever free. Lincoln responded in a letter dated August 22, 1862. “As to the policy I ‘seem to be pursuing’ as you say, I have meant to leave no doubt,” wrote Lincoln. “I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution.” Lincoln made it very clear that his “paramount objective” was to save the Union. “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” The President explained that his actions concerning slavery and persons of African descent was based on whether those actions would help save the Union. Lincoln closed his letter proclaiming, “I have here stated my purpose according to my view of Official duty: and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.”

Few abolitionists doubted that Lincoln was sincere when he declared that his personal wish was “that all men everywhere could be free.” Some, however, did not view his actions and rhetoric as being consistent. Frederick Douglass wrote in August 1862 that “the policy of the administration can be learned in two ways. The first by what it says, and the second by what it does, and the last is far more certain and reliable than the first.” Douglass noted that Lincoln had come to power as “the representative of the anti-slavery policy of the Republican party” believing “[t]hat the Union of these States could not long continue half free and half slave, they must in the end be all free or all slave.” Lincoln, Douglass pointed out, had “arrayed himself on the side of freedom.” Yet, in that same article Douglass found fault in Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief for “shielding and protecting slavery” and for “rejecting the policy of arming the slaves.” He also criticized the President for “interfering with the anti-slavery policies of some of his generals” as well as “assigning generals to important positions who were pro-slavery.” Douglass concluded that the resulting policy is to restore the Union “on the old corrupting basis of compromise, by which slavery would retain all the power it ever had.” However, one year earlier, Douglass had written that he had “very good evidence to the fact” that the Lincoln administration stood ready to enforce a policy for abolishing slavery in the Rebel states “just as soon as the people required it.”

Nine days after advising President Lincoln to add stronger language to his proclamation concerning the arming of men of African descent, Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase wrote a letter to General Benjamin F. Butler, the commanding general of the Department of the Gulf headquartered in New Orleans. Chase informed Butler that the President had suggested that it might “possibly become necessary, in order to keep the [Mississippi] river open below Memphis, to convert the heavy black population of its banks into defenders.” In Chase’s opinion the President appreciated the military necessity of arming men of African descent and of emancipating the enslaved. “I begin with the proposition,” Chase wrote, “that we must either abandon the attempt to retain the Gulf States in the Union or we must give freedom to every slave within their limits.” Chase explained that recent acts of Congress allowed the general to move aggressively toward arming men of African descent and emancipating slaves. “The acts of this last secession declare free slaves of persons who themselves engage in rebellion or aid and abet it; prohibit the return of fugitives by military commanders; and authorize the employment of slaves in the service of the Union as laborers, or in arms, or both, at the direction of the President.” Chase then encouraged Butler to take the initiative and organize African descent units. “It would hardly be too much to ask you to call, like Jackson, colored soldiers to the defense of the Union; but you must be the judge of this.” After being encouraged by Chase, Butler raised three regiments of African descent in late 1862. Though African Americans were being brought into the Union Army that fall, President Lincoln made no public announcements concerning the arming of persons of African descent.

The military success needed politically to support Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation came on the bloodiest day in American history, September 17, 1862. A humiliating Union defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August dampened Union spirits and emboldened General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. Lee went on the offensive and marched his army north into Maryland and Western Virginia. Before the battle, a corporal from the 27th Indiana Infantry made a discovery that was of great benefit to Union intelligence. The corporal found three coveted cigars in an envelope. Wrapped around the cigars was a copy of Lee’s order of battle, General Order No. 191. Though General McClellan was slow to act on the information and almost lost the advantage this information provided, the battle that ensued would be declared a Union victory. For twelve hours near Sharpsburg, Maryland, along Antietam Creek, the two opposing armies inflicted unprecedented casualties on their fellow Americans. Lee withdrew from the bloodied field. McClellan did not pursue. Calling the engagement the Battle of Antietam, the Union claimed victory while Lee’s army returned to Virginia and regrouped calling the bloody clash the Battle of Sharpsburg; and considering it a part of a larger campaign in which Lee’s army under General Thomas J. Jackson (Stonewall Jackson) had captured Harpers Ferry, the Rebels had good reason to call their Northern invasion a success.

On September 22, 1862, five days after the dubious Union victory along Antietam Creek, President Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation to which he attached the legislation on which his executive order was based. The two acts were the additional article of war signed on March 13, 1862, which prohibited military personnel from returning fugitive slaves who entered Union lines; and the Second Confiscation Act signed on July 17, 1862, which authorized the confiscation of all property in rebellious states and declared free slaves held by supporters of the rebellion. In the Preliminary Proclamation Lincoln declared: “That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Expectedly, while abolitionists were elated, the Confederate government was appalled accusing Lincoln of inciting a servile insurrection.

The African American response to the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation varied. Some believed that the President did not write it in good faith. These individuals were specifically critical of the paragraph that addressed reparations for loyal slaveholders who willingly emancipated their slaves and the colonization of the emancipated. Henry M. Turner, the pastor of an African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, had been an outspoken critic of President Lincoln. Yet, Turner disagreed with the people who did not believe that the President wrote his proclamation in good faith. Reverend Turner wrote, “I do not doubt but that he has been worked up to it by a series of events which has transpired, but these events have only worked him out of an unnecessary caution, and a useless prudence, and not a love for slavery, because I do not believe he ever had any.” Turner believed that Lincoln’s offer of reparations to slaveholders “was a strategic move upon his part.” And Turner argued that Lincoln’s colonization plan was “a preparatory nucleus around which he intended to cluster the raid of objections” to his proclamation. Finally, Turner reasoned that it did not really matter whether Lincoln issued the proclamation in good faith or not. “Let us thank God for it,” he declared. “Mr. Lincoln loves freedom as well as any one on earth, and if he carries out the spirit of the proclamation he need never fear hell. GOD GRANT HIM A HIGH SEAT IN GLORY.”

In January 1863, twelve years after proposing a resolution denouncing the United States Constitution, Hezekiah Ford Douglas wrote to Frederick Douglass praising Abraham Lincoln for the Emancipation Proclamation and declaring his personal commitment to the cause of freedom under the Constitution. After the acts of Congress in July 1862 in anticipation of Lincoln’s proclamation, Douglas (not a relative of Frederick Douglass) joined the Union Army. “I enlisted six months ago,” he wrote, “in order to be better prepared to play my part in the great drama of the Negro’s redemption.” To his fellow abolitionists who had argued like himself that the Constitution was proslavery, he wrote “you have no good reason for withholding from the government your hearty support.” The legislation authored and passed by the Republicans in Congress and signed by the Republican in the Executive Office had paved the road to emancipation. Radical abolitionists of African descent had indeed chosen the right party to support, and those who considered “the Constitution the foundation of American liberties” were confident they had made the right choice. Marching under the flag of their nation, thousands of African Americans like Hezekiah Ford Douglas joined the Union Army eager to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation. Douglas became a commissioned officer in that army, and Captain Douglas wrote, “For since the stern necessities of this struggle have laid bare the naked issue of freedom on one side and slavery on the other – freedom shall have, in the future, of this conflict if necessary, my blood.”