As Sherman’s Federal forces crossed into North Carolina in early March of 1865, Confederate leadership — recognizing their numerical disadvantage — put forth forlorn efforts to protect the resources the state provided to their Southern armies. With the reins in the hands of Joseph Johnston, the Confederates set their sights on slowing Union movements before the blue-clad troops reached supplies and reinforcements in Goldsboro.

As Sherman’s Federal forces crossed into North Carolina in early March of 1865, Confederate leadership — recognizing their numerical disadvantage — put forth forlorn efforts to protect the resources the state provided to their Southern armies. With the reins in the hands of Joseph Johnston, the Confederates set their sights on slowing Union movements before the blue-clad troops reached supplies and reinforcements in Goldsboro.

The final charge of the Army of Tennessee — battle-hardened veterans of Stones River and Chickamauga who had fought and failed to hold Atlanta and Nashville — was different than any it had made before. Instead of traversing the hills of Tennessee or the mountains of north Georgia, its troops advanced across the open fields and pine stands of the North Carolina coastal plain, a “western” army fewer than 100 miles from the Atlantic coast. But geography was not the only difference: The force that had approached 70,000 men the previous spring could only muster 4,500 to fight on March 19, 1865, the decisive day of the Carolinas Campaign — a once-great army reduced to the size of a small division.

Fighting in North Carolina was sporadic for the first three years of the war, characterized by Union lodgments on the coast, with occasional inland raids, and unsuccessful attempts by the Confederacy to evict the invaders. This changed in spring 1865, when there were no fewer than 100,000 Federal soldiers in the eastern half of the Tar Heel State. Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, with two armies totaling 60,000 men and having completed his march through Georgia and taken Savannah on December 21, 1864, chose to advance overland through the Carolinas toward Virginia.

Following logistical and weather delays, Sherman moved into South Carolina on February 1, opposed by Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee, commander of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, now a ragtag force of fewer than 14,000. Hardee’s orders were to defend Charleston, but when Sherman captured the capital at Columbia on February 17, he forced the coastal city’s evacuation. On March 8, Sherman crossed into the Tar Heel State.

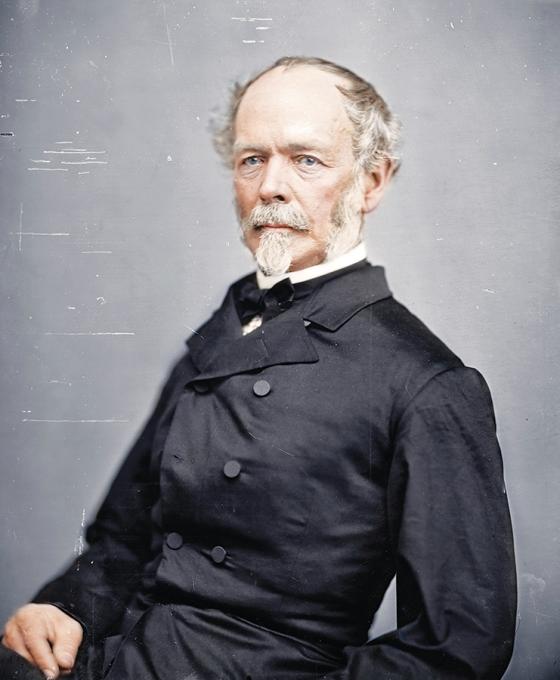

The newfound Federal focus on North Carolina was troubling, as the port at Wilmington and the state’s many farms had long been the basis of supply for Southern armies. Worse still was the thought of Sherman marching north unopposed to add his strength to the that of Grant. Someone had to take charge of the disorganized Confederate forces and give battle to Sherman. Technically, this was the job of Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, but the imaginative Creole’s plans were unrealistic and Gen. Robert E. Lee, appointed general in chief in early February, had sway to insert an alternative. The problem was that Lee’s top choice to revive the public and army’s confidence was his old friend Gen. Joseph Johnston, who did not want the job. Indeed, Johnston initially suspected a plot to make him a scapegoat, should he be forced to surrender, and anyway, President Jefferson Davis didn’t want him to have the position; this was, perhaps, the only thing they still agreed upon. Lee recalled the reluctant Johnston anyway. His orders were to form an army to drive back Sherman, but Johnston immediately tried to temper such lofty expectations.

Johnston was an obvious choice because much of his new command would be his old command, the Army of Tennessee. After that force’s disastrous battles around Atlanta and catastrophic foray back into Tennessee, the remnants were ordered east to the Carolinas. Due to a combination of attrition and transportation issues, only 4,500 infantry had made it east by mid-March. Add in Hardee’s men, Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton with a cavalry division from Lee’s army, Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s western cavalry contingent and Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Department of North Carolina, and Johnston could boast only 25,000 men of all arms.

Sherman’s objective was Goldsboro, where the railroads from the state’s ports, now under Federal control, intersected. Here, he could be resupplied and reinforced on rebuilt rail lines. Laying track as they advanced, Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s XXIII Corps and Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry’s Provisional Corps planned to meet Sherman at Goldsboro. Already outnumbered nearly 3-to-1 by Sherman, Johnston’s only hope was to fight the Union forces before that rendezvous.

Johnston hoped to oppose Sherman’s crossing of the Cape Fear River, but he needed time to concentrate his forces. To this end, Johnston ordered Hampton’s cavalry to delay the Federals. Unfortunately for him, U.S. cavalry commander Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick was doing an admirable job of screening for the advancing columns. An opportunity to defeat Kilpatrick, however, and get at the Federal infantry came on March 10 at Monroe’s Crossroads, just west of Fayetteville. Fighting was fierce, and Kilpatrick was nearly captured, but having survived their initial shock, several Federal regiments rallied. This bought time for Union infantry to arrive, forcing Hampton to withdraw.

Sherman’s rapid advance thwarted Johnston’s plans to fight for Fayetteville, and the Confederate headquarters shifted north to Smithfield, along the North Carolina Railroad. A new plan emerged: If he couldn’t stop Sherman from reaching Schofield, maybe he could stop Schofield from reaching Sherman. Johnston had little choice but to assign this task to Bragg, who was near Kinston and dispatched portions of two corps to further the goal.

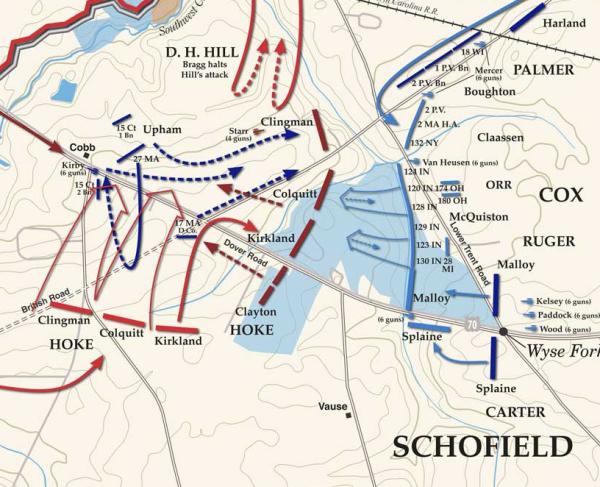

Bragg was able to concentrate 8,500 men just east of Kinston at Wyse Fork for a surprise attack on March 8 against Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox’s corps from Schofield’s command, which was busy repairing the railroad. Bragg’s assault destroyed a Union brigade and captured two regiments before running out of steam. Federal reinforcements arrived the next day, offering them a numerical advantage, but Bragg chose to stay on the offensive, moving against the Union right where strong defensive works ultimately aborted the attack. Further assaults on March 10 were beaten back with heavy losses. Unable to destroy Cox’s larger force, Bragg was at least able to delay work on the railroad, maybe slowing the junction of U.S. forces in North Carolina.

With Schofield temporarily checked, Johnston needed someone to do likewise to Sherman, who occupied Fayetteville on March 11 Rand proceeded to destroy the city’s arsenal. For this task Johnston turned to “Old Reliable” Hardee. On March 15, Hardee chose the tiny hamlet of Averasboro to deploy his 6,000 men, blocking the road employed by Sherman’s left wing, the Federal force having taken dual routes to speed the march and facilitate better foraging. The risk of this was that Sherman’s troops were not always concentrated when venturing through enemy territory, even if each half likely outnumbered any force that could be arrayed against them.

As the 27,000-man left wing neared Averasboro on March 16, Hardee tried to mitigate his numerical inferiority by employing an in-depth defense, placing two lines of untried troops in front of his veterans. The plan worked well, but knowing it was only a matter of time before enough Union reinforcements arrived to crush him, Hardee retreated after sundown. His stand bought Johnston an extra day and captured prisoners that supplied valuable intelligence — Sherman was heading to Goldsboro — but at the cost of 800 soldiers.

By March 18, Johnston had gathered all available troops, hoping to again engage Sherman’s left wing before it reached Goldsboro. Hampton, known for having an eye for terrain, recommended his camp site — just south of Bentonville and 20 miles east of Goldsboro — as a suitable place to lay a trap.

Sherman initially anticipated Johnston opposing his march on Goldsboro, but when no blocking force other than cavalry materialized, he began to relax. His complacency was made worse by Kilpatrick’s conjecture that the Confederates were falling back toward Raleigh. Thus encouraged, Sherman left to join Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard’s right wing early on March 19, believing it would soon encounter Union forces advancing from the coast. Subsequently, when the decisive day of the campaign’s largest battle began scant hours later, Sherman was absent.

Hampton recommended that Bragg’s command block the Averasboro-Goldsboro Road near the Willis Cole Plantation while Hardee — commanding both his own corps and the Army of Tennessee contingent — waited to deliver the knockout blow with a 10,000-man charge. But because of the distance that Hardee’s men had to march from Averasboro, the main assault could not begin until 2:45 p.m., and when it did, it was undermanned. The delay allowed more Federals to deploy, unnerving Bragg, who asked for help. Johnston inexplicably sent him Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’s Division, Hardee’s largest. Hardee’s assault lost nearly 40 percent of its punch before the charge even began.

The last grand charge of the Army of Tennessee was initially successful. Hardee routed one poorly deployed division and a brigade from another before bogging down in the face of a well-entrenched XX Corps, supported by five batteries. Bragg was ordered to make a simultaneous advance, but his assault was somehow delayed. This allowed a XIV Corps division to entrench in his front, which delivered a bloody repulse when Bragg finally advanced. This blunder was compounded by Bragg’s most unpardonable offense — the failure to even use McLaws’ forces, posted near an impassable swamp.

During the early phases of the March 19 battle, left wing commander, Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum, advised Sherman that he was only skirmishing, but the flight of a battle-hardened XIV Corps division, and word from captured prisoners changed his tune. By midafternoon Slocum consolidated, awaiting help from the right wing. This reinforcement took the better part of a day, but Slocum held his ground.

The prudent thing for Johnston to do was to retreat before Howard arrived, but he chose to remain on the field despite the threat of being caught between two Federal armies. Perhaps he recalled his orders from Lee to keep Sherman occupied, or perhaps he realized that continuing the fight at Bentonville was the best he could hope for mathematically. Maybe Sherman would grow overconfident and attack Johnston’s well-prepared positions like he had done at Kennesaw.

With the arrival of the right wing on March 20 the armies skirmished, but there was never the massive assault that Johnston had both hoped for and dreaded. Perplexed by Johnston’s decision to remain on the field, Sherman saw no reason to risk a general battle before Schofield, even now occupying Goldsboro, arrived.

Maj. Gen. Joseph Mower, a division commander in the XVII Corps, wanted no part in waiting, and twisted his permission to do “a little reconnaissance” on March 21 into an assault on Johnston’s left flank. The charge nearly captured Johnston and likely would have cut off the Confederates’ route of escape had it been supported, but Sherman, angry that Mower disobeyed orders, refused reinforcements. Even so, only a desperate counterattack led by Hardee gave Johnston the opportunity to order a retreat to Smithfield under the cover of darkness. The largest, bloodiest and, ultimately, final major battle fought in North Carolina ended with 2,606 Confederate and 1,527 Union casualties.

With Schofield’s arrival, Sherman’s force swelled to nearly 85,000 men, while Johnston could call upon fewer than 30,000 men. With the fall of Petersburg and capture of Richmond, Sherman’s objective shifted to eliminating Johnston’s army, and when he advanced west toward Smithfield and Raleigh on April 9, Johnston had no choice but to retreat in a last, forlorn hope to join with Lee, who, in a twist of fate, himself surrendered that day.

At an April 13 meeting in Greensboro, Johnston told Davis there was little recourse but for his army to seek terms. He met twice with Sherman to negotiate on broader topics, but on April 26, at Bennett Place, surrendered the 90,000 Confederate troops across the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida on nearly the same terms given to Lee in Virginia two weeks earlier.

Related Battles

1,101

1,500