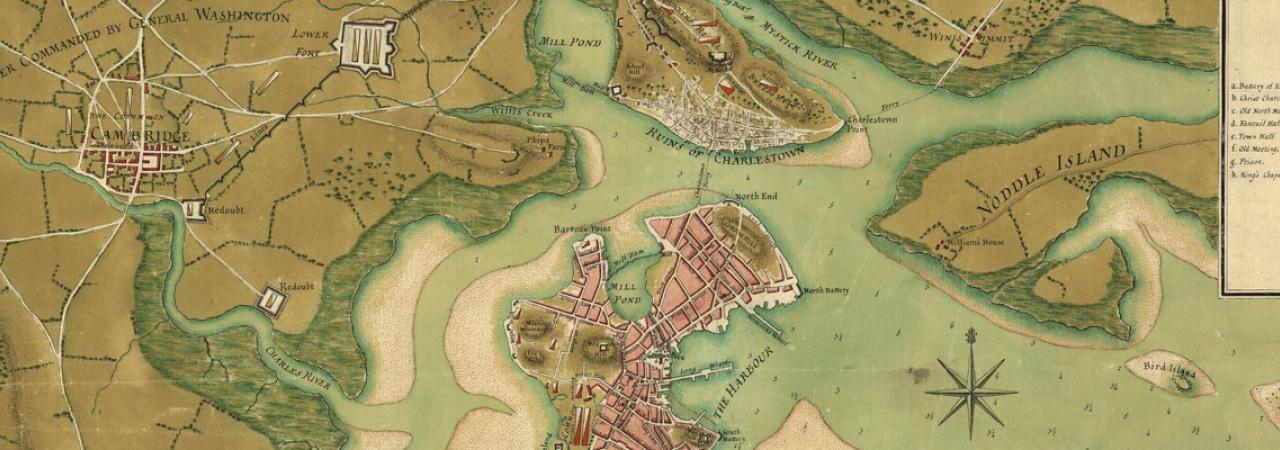

A plan of the town of Boston and its environs, with the lines, batteries, and encampments of the British and American armies.

Few incidents in American history have had a longer-lasting impact than the siege of Boston. From the first shots fired in anger at Lexington and Concord, to the miracle of Col. Henry Knox's artillery train dragged across unforgiving country to Dorchester Heights, to General George Washington's first major victory, the Siege of Boston ignited a spark within the growing American rebellion.

Long the theater of protest and division against Parliament's taxation, Massachusetts crossed the threshold into a full-scale rebellion against the British Crown. While the fuse was long and slow burning, it started in the mid-1760s with the condemnation of the Stamp Act in 1765. Following the Stamp Act crisis, Bostonians' angrer only increased. On March 5, 1770, Crown soldiers fired into a mob of civilians in what is today called the Boston Massacre. Discontent only increased. In December 1773, members of the Sons of Liberty raided a British cargo ship and dumped costly amounts of imported tea into the harbor. It seemed the restless mobs had finally struck a nerve with British authorities: tea. In retaliation, Parliament issued the Coercive Acts, which insulted and hurt the economies of many of the colonies, the Boston Port Act, which closed the harbor, and stripped the colonial assemblies of any power with the Massachusetts Government Act.

British commander Thomas Gage, a veteran of the French and Indian War, was appointed military governor of Massachusetts, removing the unpopular Royal governor Thomas Hutchinson. Capable and initially respected in the colonies, public support for Gage collapsed when he showed no intention of being sympathetic towards the patriots' complaints. However, Gage did not seek to start a war. He granted leniency to protestors and tried several times to work with colonial leaders, actions that earned him criticism from some of his officers and members of Parliament. A large portion of Londoners mistakenly thought the majority of colonists outside of Boston despised the unruly patriots. As he tried to be diplomatic, Gage received news that munitions were being gathered and stored in various towns outside of Boston. An incident in September 1774 proved successful for British troops when they captured stored gunpowder, but the response saw the mobilization of the countryside’s militias. Boston’s port closure effectively destroyed the region's main economy.

In February 1775, Parliament officially stated that Massachusetts was in open rebellion against the Crown. Tensions had not cooled off since the previous fall. In April, Gage received intelligence that munitions were being gathered and stored at a depot in Concord, a small hamlet west of Boston. On April 18, British cavalry stopped colonists to ask if they knew the whereabouts of John Hancock and Samuel Adams, two of the rebellion’s leaders. The unusual display alerted many that the British were on the move. Gage had ordered a detachment of British regulars to march west to seize the munitions at Concord. Locals detected their movements as they crossed the waterways west of Boston by boat under the cover of darkness. In response, this would be the night, along with William Dawes and Samuel Prescott, of silversmith Paul Revere’s famous ride to warn residents. The riders quickly raced through the countryside, warning residents that the redcoats were on the march. This time, colonists sprang into action almost immediately to compensate for their slow reaction to the seizure of munitions in September. This is where the term ‘minutemen’ was coined. Lieutenant Colonel Smith sent British Major John Pitcairn with about four hundred British light infantry to march forward to Concord and seize the rebel munitions. As these troops approached the town green at Lexington, on the march to Concord, the British came upon an assembled group of militia with loaded muskets. It was just after 5 am on April 19, and a few hundred armed colonists stood before His Majesty’s forces. No one is quite sure who fired first, but soon musket smoke filled the air. The following moments would see the British advance to Concord, be overwhelmed by the colonial militia, and then witness the disillusioned British retreating to Boston. As they did, the growing number of militia continued to fire upon the fleeing redcoats. Nearly two hundred fifty British troops were killed or wounded. The operation was a complete failure for Gage, and Parliament criticized his decision to move aggressively against Concord. To make matters worse, the emboldened Massachusetts men continued to pour in and approach Boston. By June, some fifteen thousand colonists had assembled under arms around Boston Harbor. Command of this new force was given to Artemas Ward. The American Revolutionary War had officially begun.

News reached Philadelphia, and the Continental Congress assembled, now had to deal with the reality that Massachusetts was at war with Great Britain. On June 14, the creation of the Continental Army was ratified. But who to lead it? Massachusetts delegate John Adams nominated the following day, June 15, Virginia Colonel George Washington to lead the new American forces gathering in Boston. Adams, ever the politician, recognized the importance of a Virginian leading the continental forces. Washington, the only member of Congress who wore the military uniform, accepted the nomination, even if he felt himself unqualified for the immensity of the position.

As Washington prepared his departure to Boston, events continued to worsen any chance of reconciliation. The Americans had surrounded Boston on the mainland, and Gage’s forces knew they had to mount an attack or face the possibility of an assault. Gage had been reinforced in late May by British generals John Burgoyne, Henry Clinton, and William Howe, along with about four thousand troops. Together, they sought the best way to fortify Boston while also driving the rebels out of the region. North of the Boston peninsula lay the small town of Charlestown, which also sat on a peninsula that jutted into the harbor. South of Boston lay Dorchester Heights, a ridge with a commanding view and tactical advantage for whoever held it over the entire harbor. And to the southwest of it lay the hamlet of Roxbury, at the foot of the land-bridge with Boston. Gage planned to send a detachment to establish a presence atop Dorchester Heights, and then assemble the remaining force to march on Roxbury and push the rebels west away from Boston. Unfortunately for the British commanders, the Americans acted first. Under the command of Colonel William Prescott, about twelve hundred militia and irregular troops crossed the Charlestown neck onto the peninsula on June 16. Under the cover of night, the mixed units built a redoubt on Breed’s Hill, the larger of the two between it and Bunker Hill, which gave a clear view of Boston to the south.

The following morning, the British command held their war council. General Henry Clinton favored a rear attack to assault the Charlestown neck, which would cut off any retreat by the Americans, and leave them surrounded on the peninsula. However, William Howe, the senior officer who was not one to take Clinton's advice, chose to lead a head-on beach invasion from the eastern bank of the peninsula. John Burgoyne concurred, assuming the rebels on the hill would scatter when approached by the British regulars. The attack commenced after 3 pm on June 17. Howe divided his army into several columns, and three assaults occurred. The Americans held their ground marvelously for the first two, sending the British regulars running back to their assembly areas. Those that did not retreat lay on the ground in bloody tangles from musket fire. The third assault concentrated the most men yet on the American redoubt on Breed’s Hill. By this point, the militia and mixed units had run out of ammunition. Soon, the British bayonet appeared over the wall, and the Americans pulled back. A well-organized retreat materialized in the rear, and most made it back over the neck to the mainland. When the smoke began to settle, the Americans had lost over four hundred men. The British had lost over one thousand, including several senior officers.

The aftermath of the battle of Bunker Hill shattered British confidence but did not break them. The British had lost over one thousand soldiers. How could they justify it? In his official report to Parliament, Gage explained how the army fell upon so many dead of His Majesty’s troops. If known for its accuracy, the report tarnished the monarchy’s confidence in Gage, and he was replaced with General William Howe as commander in chief of forces in North America.

Washington arrived in Cambridge on July 2, and immediately set about to size up his new army. What lay before him wasn’t really an army at all. The bands of encamped militia were entirely ignorant of military tactics, formations, and discipline. This was not an army. This was an oversized mob. The new American commander established order, gathered provisions, and trained the men. Among his subordinates were Major Generals Horatio Gates and Charles Lee, both British-born transplants who served alongside Washington in the French and Indian War; Major General Thomas Mifflin, Brigadier General Nathanael Greene, and Colonel Henry Knox, a former bookkeeper from Boston. None had worked together on a mission whose scale was assembling and drilling an entire army from scratch. To complicate matters, Washington had to strategize how to dislodge the British from Boston, how to remain answerable to the wishes of Congress, and how to battle elements within and outside of his control. Provisions were scarce, gunpowder scarcer; there were no artillery pieces, and smallpox was hitting the crowds of men at an ever-increasing rate.

Over the next several months, skirmishes broke out between small detachments of British and Continental troops. Most saw only a handful of volleys exchanged before a ceasefire would commence. Other times, daring raids upended peaceful spells and reminded the armies that a war was indeed being waged. Washington committed one thousand troops to invade Canada at the request of Congress with the hopes of routing the British garrisons at Montreal and Quebec, and bringing the vast territory into the American fold. It nearly succeeded except for an untimely defeat by exhausted American forces under Generals Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold at Quebec.

By winter, the British under Howe were stuck in Boston, awaiting reinforcements, and the Continental Army under Washington remained lurking on the mainland in continuous surveillance of the harbor. Of course, Washington had to contend with the daily struggles of the new army. One of the most glaring was that of enlistments. Most of the men who joined the new army had only signed on until the end of the year. That served Massachusetts well in the spring and early summer of 1775, but what of January 1, 1776, and beyond? It was one of the rare occasions where the men who walked out of camp were immediately replaced with fresh recruits. Washington would not be so lucky in the years to come. However, he now had to retrain his army all over again.

For a commander to be stuck in one of the best cities in the New World might seem a lucky break, but Howe had to contend with feeding his army. He had been ordered to evacuate Boston in November, but short on ships to evacuate his soldiers, and loyalist civilians in his care, he could not depart. Diseases such as smallpox and dysentery were striking both soldiers and civilians. Provisions for soldiers and horses were a constant headache for eighteenth-century military commanders. The British, being essentially trapped within the Boston peninsula, had minimal access to the broader resources available on the mainland. Transports were routinely sent out to raid whatever they could grab in haste, including oxen and thousands of sheep. Nearby islands and bars were looted for hay until Americans caught on and seized the materials for themselves. Firewood was scarce, leading British troops to cut down every tree in town and dismantle several buildings. In the meantime, with the cold New England winter upon them, several of His Majesty’s troops even contemplated desertion. The British command knew they had to make a move or face the impossible: defeat.

Circumstances had changed once again. In October, before Parliament, King George III had declared the colonies to be in an open state of rebellion. This effectively meant hostilities would continue and likely intensify. Both sides took the news with measured restraint. Yet, the uprising grew in size and strength. In late January, Col. Henry Knox arrived from Fort Ticonderoga with badly needed artillery for the Continental army. Washington now saw his objective: he would establish a foothold for his artillery atop Dorchester Heights and bombard the British in Boston and the harbor below. He also devised an amphibious assault, but his war council overruled this. By early March, much of the artillery had been moved to Dorchester Heights. The frozen ground made digging near impossible, so the army employed carpenters to use timber to build breastworks. Out of sight of the British, on the morning of March 6, General William Howe is said to have seen the new fortifications and exclaimed, “My God, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months.” Unlike the night before Bunker Hill, the Americans had completely surprised the British command this time. The assembly of fortifications at such speed caused the British to think that the Americans had twenty thousand men working on the hill alone.

The British tried to dislodge the American artillery, but their cannon and field pieces could not raise themselves high enough to reach the fortifications. In response, Washington, now ascending the slopes of Dorchester Heights, could be heard yelling, “Remember it is the fifth of March! Avenge the death of your brethren!” (referencing the Boston Massacre). On the opposite side of the harbor in the Charles River, nearly four thousand Continentals under the commands of Generals Greene, Israel Putnam, and John Sullivan prepared their forces to row across the harbor and land on the northern side of the Boston peninsula. Washington’s amphibious plan had finally won its day in his war council. For his part, Howe was planning to attack Dorchester Heights, a decision that many in his army questioned. Fearful of a repeat of Bunker Hill, and constantly careening their necks to gaze upward at the slopes of Dorchester, morale in the British camp was not high for the move. Howe’s decision to attack seemed to halt during his war council on the evening of May 6. The vote was to evacuate Boston and not engage the Americans. Overnight, a torrential storm blew in, possibly a hurricane, that upended any further chances of an impending battle. On March 8, Howe sent a letter to the American lines, asking Washington for a truce: Howe would not burn Boston to the ground if the Americans allowed him and the British to sail unmolested out of the harbor. The wish was granted, and nearly eleven thousand people boarded the British ships and transports, where they departed on March 17. Hundreds of loyalists were taken to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Canada, where they settled and rebuilt their lives.

As for the British army under General William Howe, the loss of Boston was a temporary setback. In reality, holding the town of Boston proved to be a weak seat to command a war. His eyes settled further south toward another formidable harbor and port: New York. From a logistical standpoint, New York would serve the British far better than Boston. It was more centered in the colonies, had ample access to the Atlantic Ocean, and the Hudson River cut north toward Lake Champlain, which connected to British-held Canada. The British thought they would be far more likely to gain an advantage if they could successfully establish a footing in New York. Washington knew this as well. And as Howe was seen leaving Boston for the Atlantic, he held no illusions where the British commander would turn up. The Continental army broke down its artillery from Dorchester Heights and marched south for New York in preparation for the campaign ahead as a unit.

Had the Americans blundered and been beaten at Boston, either by a forced error on Washington’s part, or an aggressive advance by Howe, in all likelihood, the rebellion would have collapsed, and American independence would have evaporated before it could gain serious momentum. The continuing good luck from 1775 helped solidify the uniting colonists as brethren in removing British authority from North America. The very real physical and psychological effects that victory brought to the Boston region, and then spread through the continent by the printing press and word-of-mouth, helped inspire other uprisings along the coast. By the spring of 1776, all of the colonies had overthrown their Royal governments and installed patriot representatives. Even those wary of complete independence had come around to the idea that the colonies could and should be allowed to govern for themselves. None of this would have been possible had Massachusetts not come under attack, and instead of submitting, citizens took up arms to repel the foreign invaders.

As the summer of 1776 unfolded, the winds of change were blowing in Philadelphia. A spirited optimism pushed delegates of the Continental Congress ever closer to complete independence from Great Britain. In no small part was this a testament to the oratory skill and power of Massachusetts’ John Adams. With momentum going in their direction and luck seemingly on their side, the New Englander made his case on July 1. Outside the statehouse in Philadelphia, a thunderstorm ravaged when he spoke, attempting to wrestle the message from the ears of the men in session. The time had come. And how poetic it was. As the opening of the great conflict had given hope to a North American world without British control, every member seated knew that with his vote, they would each lead the emerging country into the unknown.

Further Reading

- The Organization of the British Army in the American Revolution: By Edward E. Curtis

- Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolution Through British Eyes: By Christopher Hibbert

- The Boston Tea Party: By Benjamin Woods Labaree

- 1776: By David McCullough

- Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution: By Nathaniel Philbrick

Related Battles

19

79

450

1,054

93

300