Boston

The Siege of Boston was the first major action of the Revolution. Following the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the British army under General Thomas Gage withdrew to the relative safety of Boston. Hot on their heels were the Massachusetts militia, commanded by General Artemas Ward, who quickly surrounded the town and settled in for a siege.

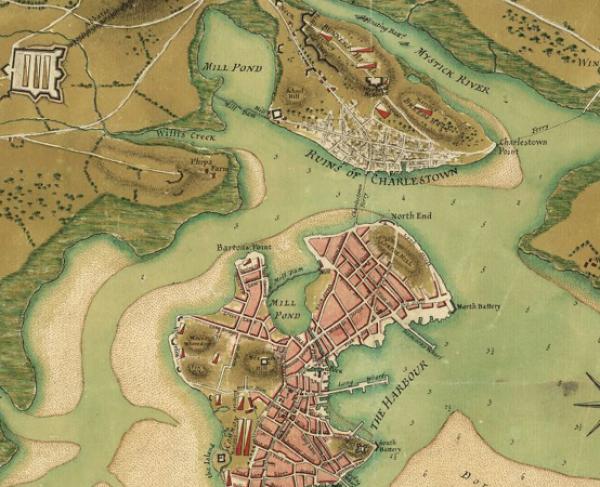

The Americans controlled the land approaches, Charlestown Neck and Boston Neck, but were unable to blockade the harbor. By this early stage in the war, the American Navy did not exist, nor could it ever content with the might of the Royal Navy. Militias from New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island reinforced the Massachusetts militias. Throughout April and May, both armies consolidated their forces and constructed defenses, skirmishing irregularly.

By June, the British had received enough reinforcements to attempt a breakthrough. Their plan was to occupy Bunker Hill to the North and Dorchester Heights to the South, using both as a base of operations against the American fortifications. Upon hearing of the British plans, Ward ordered Colonel William Prescott to preemptively fortify Bunker Hill and disrupt the British operation. Prescott set about building fortifications on the night of the 16/17. There was some debate over where to establish the earthworks, the result was a redoubt constructed on Breeds Hill, arguably closer to Boston but an inferior position, and only minor earthworks on the more strategic Bunker Hill.

When the sun rose on June 17, the British were surprised to see the extent of the American fortifications. HMS Lively opened fire, followed by the rest of the British warships and artillery; over one hundred cannon. This bombardment did little to disrupt the American fortification efforts, and only inflicted a few casualties. The first American death was Asa Pollard, who was killed instantly when struck by cannon fire. A prelude to the Battle of Bunker Hill to come later that day.

In the aftermath of the British Pyrrhic victory at Bunker Hill, both sides resigned themselves to a long siege. On July 2, George Washington arrived and took command of the American forces, now officially the Continental Army. American reinforcements also arrived from New England, the Middle Colonies, and Virginia. Some of these men were armed with the famed Kentucky, or Pennsylvania, Rifle, a critical addition to Washington’s firepower. Washington, however, lacked heavy artillery, and could neither dislodge the British nor could he risk the losses of a direct assault. The British also could not attack the American position without risking heavy losses.

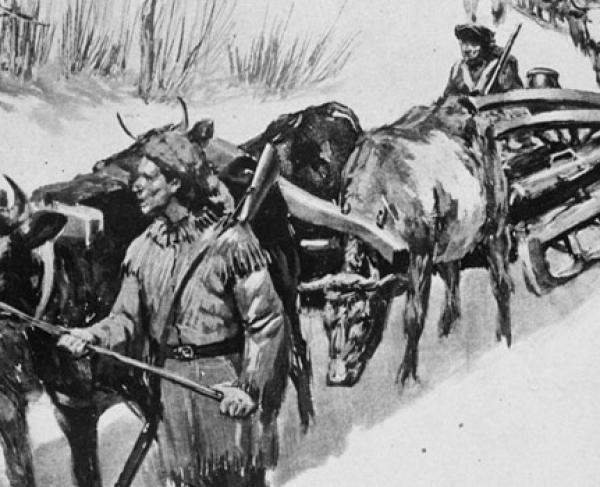

The winter was hard on both armies, with supplies running low and disease rampant. Fort Ticonderoga, which had been captured by the Americans in May, provided a key opportunity to bolster Washington’s firepower, and winter provided the means to get the cannon to Boston. Henry Knox and his “noble train of artillery” departed Ticonderoga in November, arriving in Boston by January. By March, these cannon were finally in position. On March 2, the Americans began their cannonade, with the British responding in kind. For two days, both sides hammered away with little effect.

On the night of March 5/6, Washington would make the critical decision to fortify Dorchester Heights and emplace a number of the heavy cannon. This would give him a commanding position of both the town and harbor, threatening both the Royal Army and Navy. In the morning, General William Howe, seeing the American works on Dorchester Heights exclaimed, “my god, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months.” The strength of this position, and with an assault impractical because of the weather, compelled the British to withdraw.

By March 8, the British were ready to negotiate. Some prominent citizens of Boston sent Washington a letter offering to not burn the town if they were allowed to leave unmolested. On March 9, the British attempted one final massive artillery barrage with little effect. Over the next week, the army and its supplies were loaded on transport vessels while the Navy waited for favorable winds. Those winds came on March 17, and the British sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Gage would never receive another command, Howe was heavily criticized, but Henry Clinton was relatively unscathed, commanding the army from 1778-1782. Washington had achieved a key victory, proving that the Continental Army was a match for the British, but the war was only just beginning. After securing the town, on April 4, Washington and his Continentals quickly departed, headed south to defend New York.