It has often been asserted that the American War for Independence could not have been won without the ability of George Washington to keep his army together in spite of difficult odds. Historian Joseph Ellis has said that “Washington was the glue that held the nation together.” Washington biographer Thomas Flexner called him the “indispensable man.” But there were others, too.

Two of the most unlikely American heroes of the war were Henry Knox and Nathanael Greene, men who both possessed physical challenges. Knox was missing the third and fourth fingers on his left hand, the result of a hunting accident. To conceal his disfigurement, he always kept his left hand wrapped in a white cloth. Knox was also portly, weighing in near 250 pounds, and possessed a burning ambition, a keen mind, and a highly gregarious nature.

Greene walked with a limp. He was just as gregarious as Knox and quite flirtatious with women. Raised in a strict Quaker household in Rhode Island, Greene rebelled against his religious foundation particularly when it came to studying the arts of war and women. He loved to dance and was good at it. Often he snuck out from home to attend socials in Kent County. According to one biographer, his limp may have been the result of a fall when Greene was trying to escape through a window to attend one of these socials.

As tensions mounted in Boston between inhabitants and British authorities, the colony of Rhode Island began to organize militia units. Caught up in the fervor of excitement of the tenor of the times, combined with his deep interest in the arts of war and military history, Greene enthusiastically joined the newly forming local militia company, the Kentish Guards. Much to his bitter disappointment he was not elected, as he had expected to be, an officer. While women seemed to not mind or notice his limp, it proved problematic to his military brethren. Sensitive to criticism, he considered resigning. Yet he remained steadfast in his commitment to the Kentish Guards, drilling with them as a private. After Lexington and Concord he was sent by the Rhode Island Committee of Safety, now the colony’s ad hoc government, to Boston to serve as part of its contingent that continued to hem the British inside Boston. He was appointed Major General of Rhode Island troops. Greene arrived in Boston just after the Battle of Bunker Hill. As the Continental Army began to cohere under George Washington, Congress appointed Greene a Brigadier General in Washington’s force. He was thirty-three and in a short period of time been promoted from private to general; from a small colony he was now thrust on the national stage bearing significant responsibilities.

In the years prior to the Revolution, Greene and Knox were close friends, even kindred spirits. Greene, who regularly traveled to Boston on business, could often be found visiting Knox in his London Book Store. They shared a love of literature, the classics, and in particular military history, which they pored over in books and discussed in lively conversation. Unbeknownst to both of them, they had embarked on a journey of self-tutorials on how to be a soldier and how to fight in wars. Their informal study proved its worth during the forthcoming war. Knox in particular was drawn to study artillery and in the Continental Army he would be the chief architect of Washington’s artillery wing.

When Washington assumed command of the Continental Army in Boston after the Battle of Bunker Hill, he recognized immediately the value of making Greene and Knox part of his intimate military family. During the War for Independence both Knox and Greene would share with Washington and his soldiers the privations of war and the shame associated with stinging defeats, and would contend with the sometimes bitter infighting that took place within Washington’s command structure. Together they served for the eight-year duration of the war, being among the few who rose through the ranks to stand with their commander-in-chief.

Upon joining Washington’s inner circle, Knox immediately went to work trying to figure how to best remove the British from Boston. Because he was a native of the area he was well versed in the topography. Knox believed that the British could be forced to evacuate the city if the Continental Army could fortify the various hills around the city, most prominently Dorchester Heights. The question was where to get the guns. In May 1775, Fort Ticonderoga fell into Patriot hands, captured by Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys and Benedict Arnold. With this coup came the large cache of artillery so badly needed for the American cause.

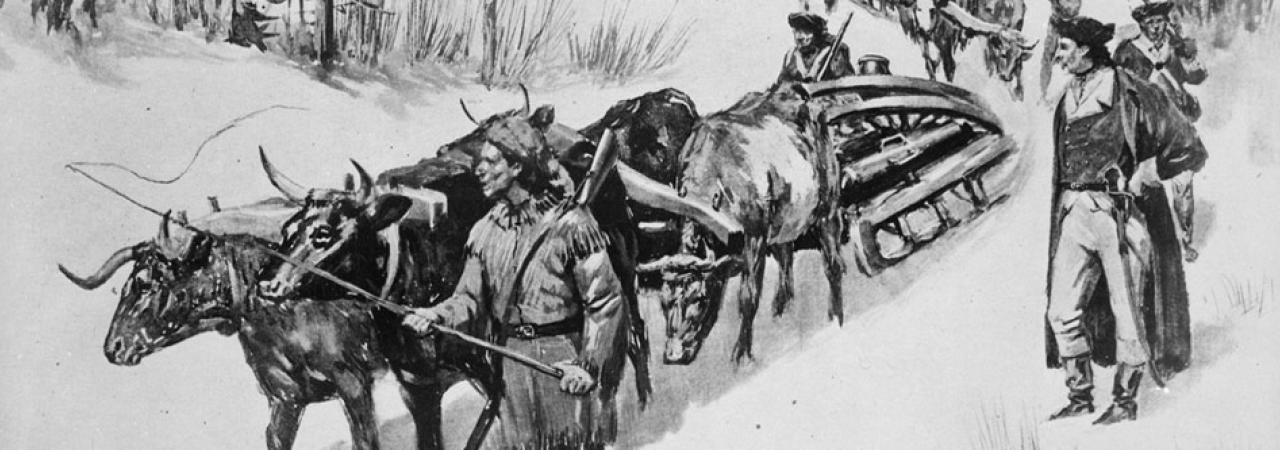

The twenty-five year old Knox hatched a plan to go to Fort Ticonderoga, retrieve the cannons and bring them back to Boston and Washington’s Army. With Washington’s blessing, Knox and a contingent of hearty men headed out on November 16, 1775. Arriving at the fort on December 5, the energetic Knox began to take inventory of what was to be had. Using his self-trained eye he settled on 58 pieces-- mostly mortars and 12 and 18-pound cannons and their required munitions. During the close to 300 mile trek lugging their treasure back to Boston, Knox and his men endured severe winter weather conditions, but they proved to be inventive in figuring out how to haul tons of guns over freezing cold lakes and rivers, sometimes caked with ice, bitter cold, snowfall and subsequent thawing, as they struggled with their oxen teams on specially designed sleds to cross the Berkshire Mountains of Western Massachusetts. All along the route Knox kept his wife informed in letters and maintained a diary in which at one point he wrote, “It appeared to me almost a miracle that people with heavy loads should be able to get up and down such hills.” The train arrived in Boston by mid-January 1776, completely intact, not a gun lost. With this formidable battery at his disposal, Washington was able to implement Knox’s plan of siege. In March, shortly after the Dorchester Heights were fortified, the British evacuated the city.

Knox had achieved the nearly impossible and Washington in his gratitude appointed him Chief of Artillery. Knox would be by Washington’s side throughout the rest of the war.

Greene would be with Washington, too, during most of the war. Washington came to admire Greene’s knowledge of tactical deployment of troops. Some historians contend that had Greene not been laid low with an illness during the Battle of Long Island in August 1776, the disastrous rout of the Continental Army may have been averted.

Like Knox, Greene earned Washington’s trust while serving as one of his wing commanders during the Battle of Trenton, helping to delay the British at the Battle of Brandywine, and enduring the crucible of Valley Forge.

In 1780, the focus of the war shifted to the South. On August 16, General Horatio Gates and his Southern Department of the Continental Army were soundly defeated in the debacle of the Battle of Camden, South Carolina, leaving the Southern Patriot forces in shambles. Gates was removed from command, and Congress granted Washington his own discretion as to who to appoint to replace him. Washington immediately dispatched Greene. Greene’s organizational skills as well as his grasp of both strategy and tactics served him well during the campaign in the Carolinas.

His greatest moment came at the Battle of Guilford Court House in March 1781, a pyrrhic victory for the British, in which Greene skillfully deployed varying elements of his command at different times of the battle to parley British troop movements. Ever the astute student, Greene took a lesson from the tactical playbook of Daniel Morgan employed two months earlier at the Battle of Cowpens, South Carolina. Like Morgan, he arranged his troops in three lines, luring the British to launch their attacks against each line, which would then withdraw. The British in hot pursuit, smelling victory, would then encounter a wall of gunfire from the next line, which was unexpected. The staggering losses suffered by the British put in motion the withdrawal of British General Lord Cornwallis to the Virginia coast and his subsequent defeat at Yorktown. While Greene was not at the October 1781 surrender ceremony, he was just as much a part of the American success story as was Henry Knox, who stood with his commander to receive the British surrender.

Neither Knox nor Greene were superheroes. They were like so many of those who served in the Continental Army: amateur soldiers who were very human and who bore their physical vulnerabilities with grace and dignity. They made up for their physical limitations with their ability to lead and inspire men to do the seemingly impossible. In doing so, they secured for posterity a nation that strives to give each person, no matter their limitations, an equal chance at achieving success.

Related Battles

19

79

1,310

532