If everything had gone according to General John Burgoyne’s plan, 1777 would have been the year the British Empire put an end to the rebellion in its North American colonies.

In August 1776, an army of 32,000 British soldiers under the command of General William Howe, carried across the Atlantic the largest fleet in British naval history, had driven George Washington and the Continental Army out of New York City, then out of New York entirely. While Washington had kept the nascent American cause alive with dramatic victories at Trenton and Princeton, his position remained precarious.

Back in London, General John Burgoyne proposed a plan for the campaign of 1777 that would crush Washington’s army and cut out the heart of the rebellion. Howe would advance his army up the Hudson River from New York City, while Burgoyne would move south from Canada with a second force. These two armies would crush Washington between them and link up at Albany, destroying the rebel army and cutting off New England, the heart of the rebellion, from the rest of the Thirteen Colonies.

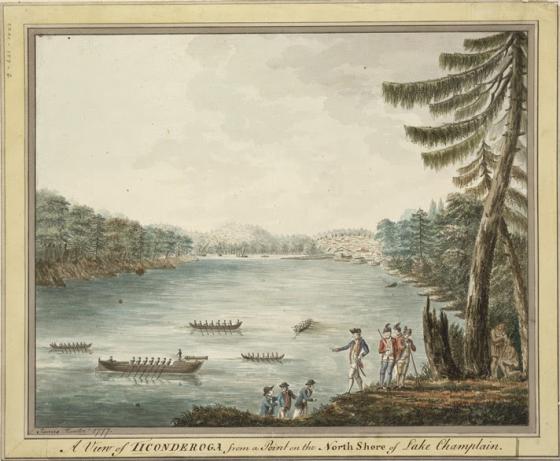

General Burgoyne and his army of nearly 8,000 British regulars, Hessians, American Loyalists, and Native Americans began their campaign in mid-June. The first obstacle that Burgoyne would have to overcome was the American defenses at the southern end of Lake Champlain, around Fort Ticonderoga.

In 1777, Fort Ticonderoga was already a historic location. The fort had been constructed by the French in 1755, during the French and Indian War. In 1758 British troops tried and failed to capture the fort in the bloodiest battle fought in North America until the Civil War. The British succeeded in taking possession of the fort the next year when the French abandoned it and retreated north into Canada. In May of 1775 Fort Ticonderoga was captured by Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys militia. Artillery from the fort was transported south during the winter of 1775 and placed on high ground outside Boston in March of 1776, which forced the British to evacuate the city.

Fort Ticonderoga was the Americans’ first line of defense against a British invasion from Canada. In addition to the fort itself and the French Lines, the old entrenchments outside the fort left over from the battle in 1758, the Americans had also constructed fortifications on Mount Independence on the other side of Lake Champlain. Burgoyne and his army would have to overcome these positions in order to continue their advance south towards Albany.

Burgoyne commanded nearly 8,000 men, while the Americans under General Arthur St. Clair numbered around 2,000. To capture Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence, Burgoyne split his army in two. A force of German troops, mostly from Brunswick and Hesse-Hanau and commanded by Major General Friederich Baron von Riedesel, landed on the east side of Lake Champlain. Their goal would be to surround Mount Independence and cut off the military highway that ran from Fort Ticonderoga, across a bridge over Lake Champlain, and south into New Hampshire. On the west side of the lake, the redcoats advanced to surround and besiege Fort Ticonderoga.

The Hessian advance was slowed by difficult terrain, but the British made fast progress. On July 2, soldiers from Brigadier Simon Fraser’s Advance Corps captured the outermost American positions at Mount Hope. Over the next three days, the British troops surrounded Fort Ticonderoga on its landward side. On July 5, British troops occupied the summit of Sugar Loaf Hill. This piece of high ground overlooked both Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence, but it had been left unfortified by the Americans. General St. Clair had not sent troops to guard Sugar Loaf Hill because there was no source of freshwater available to men camped on the summit.

Cannons mounted on Sugar Loaf Hill could dominate the American positions, but placing artillery on Sugar Loaf Hill would require cutting a road up the forested hillside, and manhandling the heavy cannons to the summit. British Major General William Philips famously claimed that, “Where a goat can go, a man can go, and where a man can go, he can drag a gun.”

When the Americans in Fort Ticonderoga spotted British troops and campfires on the summit of Sugar Loaf Hill, General St. Clair ordered the immediate evacuation of the fort and Mount Independence, to be carried out that night. Supplies, wounded soldiers, and noncombatants were loaded onto a fleet of boats, which set sail up Lake Champlain to the port of Skenesboro. The garrison of the fort retreated across the bridge over the lake and linked up with the garrison of Mount Independence. The army marched south and by the next morning, they had reached Castleton (in modern-day Vermont). The British were unaware that the Americans had abandoned their positions until the morning of July 6. Burgoyne left a small garrison to occupy Fort Ticonderoga and began pursuing the retreating Americans.

When news of Fort Ticonderoga’s fall reached London, King George III is said to have burst into his wife’s bedroom and exclaimed, “I have beat them! I have beat all the Americans!” Yet Burgoyne’s success would be short-lived. The British were unable to catch the American force before it joined up with reinforcements further south. Many of the American soldiers who escaped the siege of Fort Ticonderoga would eventually take part in the Battles of Saratoga, where Burgoyne was defeated and forced to surrender.

Further Reading:

- Fort Ticonderoga: Key to the Continent By: Edward Pierce Hamilton

- The British Army in North America 1775-1783 (men at Arms Series, 39) By: Robin May

-

The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire By: Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy

- With Zeal and With Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 By: Matthew H. Spring

Related Battles

330

1,135

367

190