Out of all the weapons and tools on a battlefield, the infantryman’s musket or rifle is the most important. In the century spanning the American Revolution to the Civil War, small arms technology underwent significant changes, while remaining incredibly similar. Because of this, linear warfare still dominated Civil War battlefield tactics a century after almost identical tactics were used during the Revolution.

Smoothbore weapons dominated the battlefields of the Revolution and War of 1812, even seeing service on the early battlefields of the Civil War. The Civil War, however, would begin the era of the rifle, and rifles began to be standard issue to infantry units. Rifles did see action in the earlier conflicts, but were fewer and reserved for specialized units rather than the average infantryman.

The Revolution

The American Revolution was dominated by the smoothbore, flintlock, muzzle loading, musket. Infantry tactics of the time favored speed over accuracy, and the small arms reflected this. Projectiles, round balls “rounds,” were smaller than the barrel, adding speed to the cumbersome reloading process, and alleviating the fouling caused by black powder residue. A trained solider was expected to fire three rounds a minute in massed volleys.

Most muskets were lethal up to about 175 yards, but was only “accurate” to about 100 yards, with tactics dictating volleys be fired at 25 to 50 yards. Because a portion of the powder in a cartridge was used to prime the pan, it was impossible to ensure a standard amount of powder was used in each shot. This meant that muzzle velocity widely varied, and there are even some stories of soldiers being struck by round balls but suffering no more than a deep bruise.

The British Redcoat was armed with the Short Land Pattern musket, often called the “Brown Bess.” German units serving with Great Britain often carried the same muskets as the British Regulars, but were also equipped with German made weapons, especially light infantry weapons such as the Jäger Rifle. The limited cavalry that saw action in North America carried shorter carbine versions of infantry weapons, and occasionally flintlock pistols.

The Continentals, both regulars and militia, carried a motley assortment of small arms. Where possible, units attempted to acquire either British Short or Long Land Pattern muskets, or French Charleville muskets. The Continental Congress was able to produce a limited amount of “Committee of Safety” muskets, often clandestinely made by the revolutionary committees to avoid British prosecution.

Militias, particularly Continental militias, often carried whatever weapons they had at home. This included a wide range of military style muskets from the British, French, Dutch, or Spanish, some dating back to the early colonial period. In addition, many hunting style weapons found their way onto Revolutionary War battlefields, including, hunting muskets, fowling pieces, and in rare cases, rifles.

War of 1812

With only a short thirty years spanning the end of the Revolution and the War of 1812, small arms changed little. Smoothbore, flintlock, muzzle loading, muskets were still the primary weapon carried by both sides. Standardization increased between the wars, and a smaller variety of weapons saw action during the War of 1812.

For the British, the Land Pattern “Brown Bess” was still the standard infantry small arm. The Land Pattern had undergone another modification in 1797, this Third Model or India Pattern, was shorter and lighter than the Short Land used during the Revolution. The rise of Light Infantry tactics saw purpose built muskets, and in growing numbers rifles, issued to specialist troops. The best example of this was the New Light Infantry Land Pattern muskets carried by the 43rd Foot at the Battle of New Orleans.

While the Springfield Armory, founded in 1777, traces its origins to the Revolution, it was not until the War of 1812 that American small arms manufacturing hit its stride. The Model 1795 musket borrowed heavily from the Model 1763 and 1766 French Charleville musket, and was the first mass produced American military small arm. Like its French predecessors, the Model 1795 was a smaller caliber than the British Land Patters, and the ball fitted more snugly in the barrel, giving it a slight advantage in range and accuracy, and giving the United States a slight edge on the battlefield. So important was the Model 1795 to the US Army, it appears as the infantry’s branch insignia.

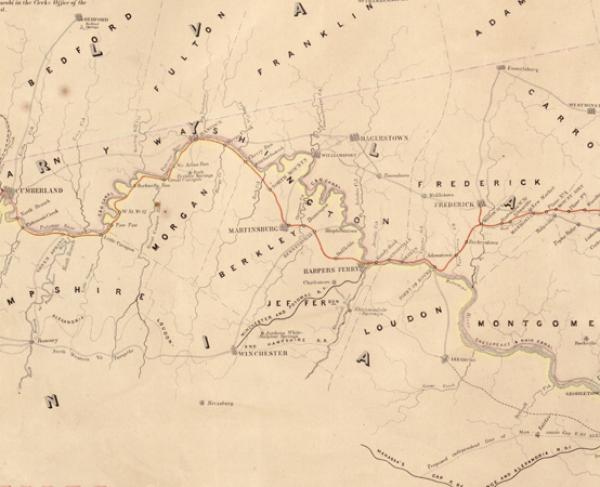

The War of 1812, and the Napoleonic Wars, can be seen as the rise of the rifle. Seeing the efficacy of similar British units during the early years of the Napoleonic Wars, specifically the 60th and 95th Rifles, the United States decided to follow suit. In 1808, Congress formed the Regiment of Riflemen and armed them with the Model 1803 rifle produced at Harpers Ferry. These troops saw action in Canada and in the Western Theater, with their major actions taking place at Tippecanoe, York, and Big Sandy Creek.

Civil War

The American Civil War was a time of rapid technological advancement, and small arms were no different. Early in the war, some of the weapons on the battlefield had also seen action during the War of 1812, fifty years earlier. Most were converted from flintlock to the newer, more reliable, percussion cap. Some had even been rebored and rifled. The Civil War was when the rifle, augmented by the Minié Ball, came to dominate and devastate the battlefield.

The Springfield Model 1855, the first rifled musket, was the first to use the new type of ammunition, as well as the Maynard tape priming system. This extended the effective range out to 300 yards, with accurate fire up to 100 yards. The Model 1855 saw service on both sides, especially after the Confederates captured Harpers Ferry and moved the machinery, which was producing the Model 1855, to Virginia.

With the outbreak of war, the Union realized that it needed arms on a scale never before seen in United States history. Springfield armory quickly moved to simplify the Model 1855, creating the workhorse of the Civil War, the Model 1861. The only major change being a return to the percussion cap system.

Over a million Model 1861s were produced, and saw extensive action with both sides. In the hands of a skilled soldier, the Model 1861 could accurately hit a target 500 yards away, a fact emphasized by the sights that came standard with every weapon. The technology of war was advancing rapidly, and tactics were lagging behind, with the average engagement range of 60 yards on a Civil War battlefield it is easy to see why casualty numbers became so horrific.

For the Confederacy, chronic arms shortages led to purchasing weapons overseas. The English made, Pattern 1853 Enfield rifled musket was the second most used firearm of the war, and coveted by Confederate infantrymen. The Enfield was almost identical to the 1861 Springfield, but imported Enfields were often not of the highest production quality, resulting in a difficulty repairing and replacing parts. In the hands of a trained solider, the Enfield was as lethal as the Springfield.

Like the in the previous wars, it was the specialist troops that had access to the cutting edge of small arms technology. For the Civil War, this meant the move towards multi-shot, often breech-loading, weapons. The need for an effective cavalry weapon drove much of the technology. While a plethora of weapons saw action during the war, the two most important were the Sharps and Spencer rifles.

Designed in 1848 the Sharps rifle can be seen as the beginnings of the transition from muzzleloaders to breechloaders. The Sharps utilized a “falling block” mechanism that lowered the breech and allowed a cartridge to be loaded from the rear of the gun. A percussion cap was still needed to fire each time, and was placed after cocking the hammer. While still a single shot weapon, moving from muzzle to breech loading increased the rate of fire to between eight and ten rounds per minute. Sharps carbines, shorter and lighter versions of the rifle, also saw action with cavalry forces.

Renowned for its accuracy and range, Sharps rifles were famously used by the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters. Formed by Hiram Berdan, the Sharpshooters were the premier light infantry of the Union Army, and were armed with the Sharps after May 8, 1862. In the hands of one of the green-coated Sharpshooters, the Sharps rifle was lethal at long range, and the high rate of fire compounded the damage the Sharpshooters could do.

The Spencer rifle was the pinnacle of military technology during the Civil War, the world’s first military repeating rifle. Utilizing a lever action and a magazine holding seven brass rimfire cartilages, a Spencer rifle were capable of firing up to twenty rounds per minute, seven times faster than the standard infantry rifled muskets. The use of a magazine, which was a tube inserted into the butt of the rifle, was revolutionary, and greatly affected the rate of fire.

The Ordnance department resisted any use of repeating rifles, fearing that the average infantryman would waste ammunition by firing rapidly, resulting in a lack of supply. The cost of the new breechloaders also was a major factor. Because of this, the Spencer saw limited action during the war. Some Union cavalry, most famously at Gettysburg, carried the smaller carbine version and Spencers saw larger usage in the Western theater.

At the end of the Civil War, new small arms technology had proven their efficacy on the battlefield. Tactics, however, still lagged behind, with Civil War battlefield still looking similar to those of the American Revolution. The next generation of leaders would have to tackle how to utilize the new technology on the battlefield. One only has to look forward fifty years to the First World War to see the impact of new technology on the battlefield, and the carnage that it would wreak.