In July 1864, Union General William T. Sherman observed during the Atlanta Campaign, “The skill and rapidity with which our men construct these is wonderful and is something new in the art of war.” Over the course of a few years, infantry tactics shifted as technological innovations increased the range and firepower of weaponry. Soldiers created various types of earthworks and entrenchments to try to protect themselves in battle during the American Civil War. Sometimes, these protections were prepared quickly on battlefields. Other times, long lines of entrenchments purposely positioned or encircled an enemy’s position, creating siege-like conditions with complex trenches that foretold the trench stalemate warfare that would emerge in the early 20th Century.

When volunteers rushed to enlist in Union or Confederate armies in 1861, most American military leaders relied on tactics that resembled 18th Century military movements: massing infantry troops in large columns or lines and marching against similarly prepared enemy troops. This type of combat reflects tactics from the American Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars when smoothbore muskets’ comparatively short range allowed infantry to march close, fire, and bayonet charge. Earlier warfare did use fortifications defensively or in siege operations, but rarely dug-in on fields of battle.

However, many Civil War soldiers carried rifled guns. The invention and production of the Minie-ball and grooved, rifled barrels of guns increased the distance of shots. Old-school tactics that brought troops close to the enemy on an open battlefield now mowed down soldiers in bloody ferocity with the newer weapons. While it would take time for officers to adopt tactics in their battle strategies, soldiers sought cover and began to form the idea that it was not shameful to take cover and fire on enemy soldiers from a protective posture.

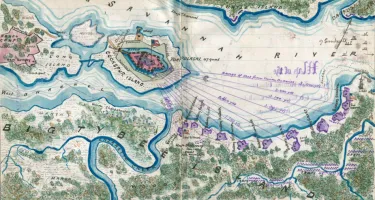

By 1862 and 1863, some battles found soldiers taking shelter, digging fieldworks or rifle pits for protection and officers establishing lines to build these temporary protections. To defend a key location like Washington D.C., Richmond, Vicksburg, or other cities, series of forts or defensive entrenchments were dug and defended. To counter these defensive works, an attacking army built their own entrenchments, beginning to encircle the enemy’s position.

The following years of war—1864-1865—saw significant changes in this type of warfare. The Overland Campaign in Virginia and the Atlanta Campaign in Georgia are strong examples of armies and advancing or defending and using entrenchments as intentional parts of the plans. Remarking on his experience in the Overland Campaign, Union General Joseph Bartlett compared, “We have never before used the Spade as we have this summer. In any two days of the campaign we have constructed more works than were thrown up by us two years ago during the whole time we were in front of Richmond [in 1862].”

While piled up dirt offered some protection from enemy fire, a different type of waiting, watching, and sharpshooting occurred. Rice Bull from the 123rd New York Infantry noted in his diary about the experience under fire in entrenchments near Atlanta: “As soon as a man showed himself during the daylight a bullet would come. Not more than one shot in fifty hit its mark, but it was nerve-wracking…. Every day someone in the Regiment was hit.” When officers ordered troops to leave the limited protection of the earthworks and make charging attacks against enemy lines, casualty numbers were often high.

Warfare in these primitive trenches had plenty of danger and boredom. Massachusetts-man Walter Carter’s letter reflects attitudes of soldiers on both sides as they waited in trenches. “Still we lie here, in the trenches, doing nothing all day long; the burning rays of the sun, the dry, parched ground, ready to be blown away in clouds of dust by the slightest breath of air…. I guess I can stand two months of siege work; no more charging to be required of your humble sergeant-major….”

Civil War armies still marched into open fields to fight, but more and more often as the war years passed, soldiers dug fieldworks for protection. Staying semi-stationary in types of battle or siege lines produced larger, deeper trenches and hinted at the changes coming to the practice of warfare.

The following terms—retrieved from this Civil War Glossary—offer some of the types of entrenchments or fortifications along with photographs to visually illustrate.

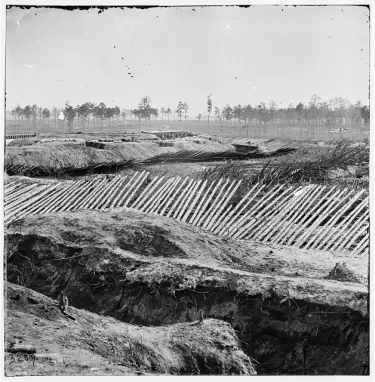

Abatis: (pronounced ab-uh-tee, ab-uh-tis, uh-bat-ee, or uh-bat-is) A line of trees, chopped down and placed with their branches facing the enemy, used to strengthen fortifications.

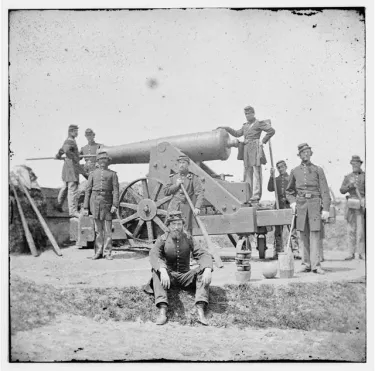

Barbette: Raised platform or mound allowing an artillery piece to be fired over a fortification's walls without exposing the gun crew to enemy fire.

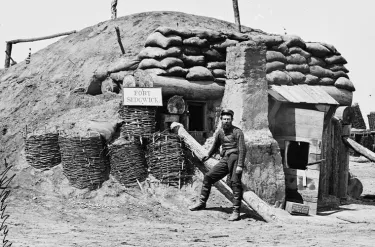

Bombproof: A field fortification which was made to absorb the shock of artillery strikes. It was constructed of heavy timbers and its roof was covered with soil.

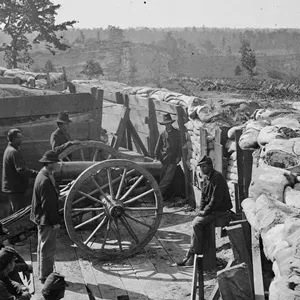

Breastworks: Barriers which were about breast-high and protected soldiers from enemy fire.

Earthwork: A field fortification (such as a trench or a mound) made of earth. Earthworks were used to protect troops during battles or sieges, to protect artillery batteries, and to slow an advancing enemy.

Entrenchments: Long cuts (trenches) dug out of the earth with the dirt piled up into a mound in front; used for defense.

Fieldworks: Temporary fortifications put up by an army in the field.

Fortification: Something that makes a defensive position stronger, like high mounds of earth to protect cannon or spiky breastworks to slow an enemy charge. Fortifications may be man-made structures or a part of the natural terrain. Man-made fortifications could be permanent (mortar or stone) or temporary (wood and soil). Natural fortifications could include waterways, forests, hills and mountains, swamps and marshes.

Gabions: (pronounced gey-bee-en) Cylindrical wicker baskets which were filled with rocks and dirt, often used to build field fortifications or temporary fortified positions.

Lunette: (pronounced loo-net) A fortification shaped roughly like a half-moon. It presented two or three sides to the enemy but the rear was open to friendly lines.

Rifle Pit: Similar to what soldiers call a “foxhole” today. Rifle pits were trenches with earth mounded up at the end as protection from enemy fire. A soldier lay in the trench and fired from a prone position.

Siege lines: Lines of works and fortifications that are built by both armies during a siege. The defenders build earthworks to strengthen their position inside a fort or city against assault while the besieging army constructs fortifications to protect siege guns and soldiers from sharpshooters inside the city.

Traverse: A mound of earth used to protect gun positions from explosion or to defilade the inside of a field work or fortification

Further Reading:

- In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications and Confederate Defeat by Earl J. Hess, (University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

- Fighting for Atlanta: Tactics, Terrain, and Trenches in the Civil War by Earl J. Hess, (University of North Carolina Press, 2018).