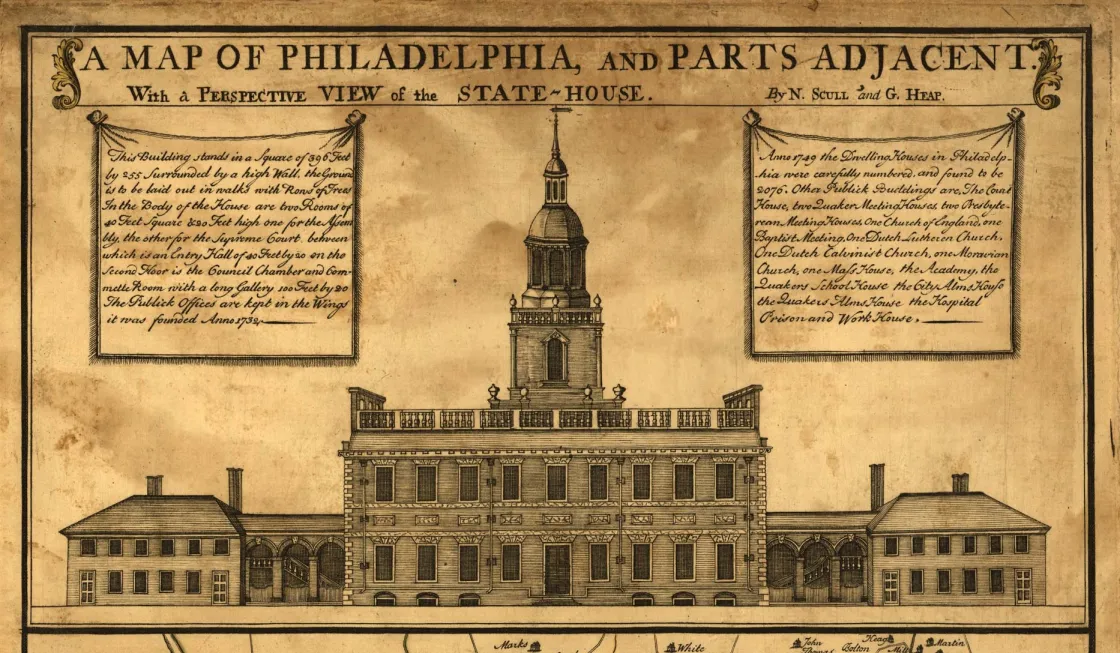

Philadelphia fell to the British on September 26, 1777, without a shot fired that autumn day. The capital of the rebellious American colonies was now in the possession of Sir William Howe and the British army. There remained a significant issue, besides the fact that General George Washington’s Continental Army was still intact. Philadelphia lay astride the western bank of the Delaware River, which was eventually depended on for supplies, communications, and any potential reinforcements for Howe’s occupying force. Therein lay the problem.

Downriver from Philadelphia sat two forts, Fort Mifflin on the Pennsylvania side of the river and Fort Mercer on the New Jersey shore. Both remained in possession of the Americans. Along with impediments in the river, these forts choked off any potential British use of the Delaware and could effectively be used by the enemy to besiege Howe’s force in Philadelphia. The forts had to be subdued or Howe’s occupying force could face dire straits throughout the upcoming winter.

Fort Mercer, named for the fallen American general Hugh Mercer, who had been mortally wounded at Princeton on January 3, 1777, was constructed on the 400-acre plantation of James and Ann Whitetail. The earthen fort was constructed under the experienced eye of the Polish engineer, Thaddeus Kosciuszko, who the previous year had overseen the building of Fort Billingsport which stood approximately ten miles downriver from Fort Mercer’s location. When the soldiers completed Fort Mercer, the fortification was approximately 350 feet long, nearly 1,000 yards wide, could hold a garrison of 1,500 men, and boasted 14 artillery pieces. By October 1777, though, only 250 men garrisoned the fort.

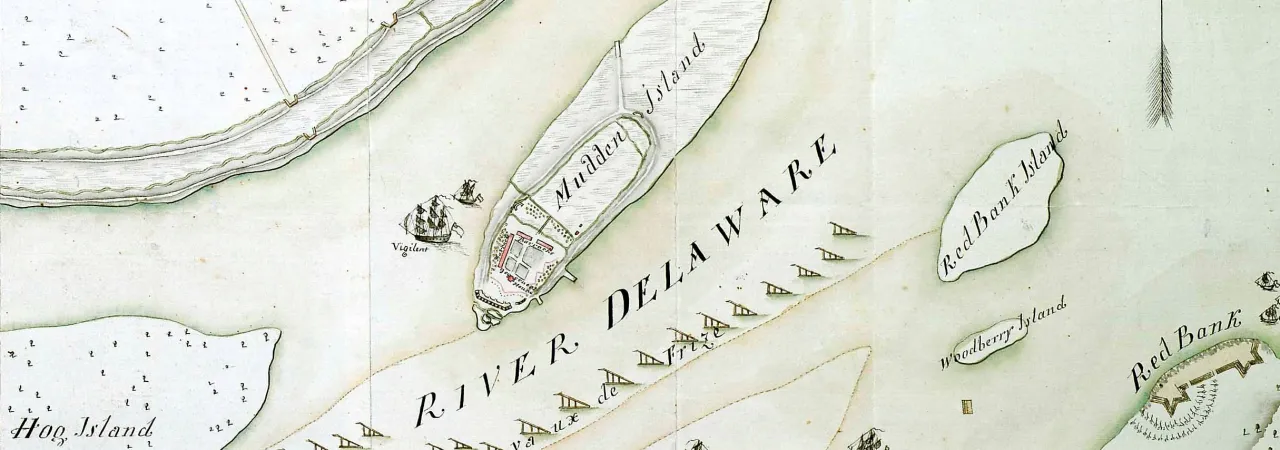

On a speck of land called Mud Island sat Fort Mifflin, named for the Pennsylvania revolutionary and major general, Thomas Mifflin. Interestingly, the site was identified in 1771 by Captain John Montresor, a British engineer and cartographer who had overseen the beginning of a construction of a fortification at that spot. Pennsylvania’s royal governor in 1771, John Penn, had asked General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief of British forces in North America to dispatch someone that had intimate knowledge of building defenses, for the purpose of monitoring maritime traffic entering and exiting from Philadelphia at that time.

By the time of the American Revolution, only the eastern and southern walls of the fort were completed, both made from stone. Benjamin Franklin, in charge of the committee tasked with providing options for the defense of Philadelphia, recommended the fort’s final two walls be completed. They were completed by the end of that same year, 1776.

Across the river, the Continentals placed a variation of the chevaux de frise, sharpened wooden stakes that were effective 18th-century cavalry impediments. Sinking wooden-framed boxes, approximately 30 feet square, with sharpened logs tipped with iron spikes. Connected by a chain and with spaced intervals to allow friendly ships to pass through, the boxes sat at an oblique angle and lay in wait for an unsuspecting wooden hull to be gutted as it passed through. An impromptu river navy under Commodore John Hazelwood also provided some defense for the Americans.

By mid-October, the two forts, as Fort Billingsport was quickly abandoned by the Americans and the guns spiked, along with the chain barrier across the Delaware awaited the British onslaught.

The British had not been resting during this time, however. Construction of batteries on Province Island exactly opposite Fort Mifflin had been started, and by October 11, the bombardment of the American fort began. Under the shriek of shot and shell, siege preparations were started by the British infantry, cutting off any approaches to the island. For the American defenders, the haphazard bombardment proved more of a nuisance, interrupting repairs on the fort and testing nerves. For the British, the artillery firing provided cover to move against Fort Mercer. Being on land, Howe believed that the fort would be easier to strike and the fall of one fort would necessitate the fall or evacuation of the other; similar to what had happened the previous year with the fall of Fort Washington, in New York and Fort Lee, in New Jersey, across the Hudson River.

On October 22, Hessians under the command of Colonel Carl von Donop with approximately 2,000 men advanced on Fort Mercer in what would become known as the Battle of Red Bank. Fort Mercer and its garrison, had grown to approximately 500 men under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene, a distant cousin of Nathanael Greene. This included the 1st Rhode Island Regiment under Greene and Colonel Israel Angell’s 2nd Rhode Island augmented by additional troops.

Interestingly, Howe either had given no explicit instructions or Donop was given full discretion to advance on the fort as the situation dictated. The land force would be augmented by five ships from the British Navy. With the wooden ships came 184 artillery pieces to shell Fort Mercer.

A mile from the Hessian landing spot on October 21, the New Jersey militia welcomed the German mercenaries to New Jersey and began a delaying action back to the fort. The next morning, Donop sent forward a British officer to give Greene the option of surrender. The message was simple:

“The King of England orders his rebellious subjects to lay down their arms, and they warned that if they stand battle, no quarter will be given.”

Greene’s reply was simple and straightforward, delivered by the American officers sent to communicate with their British counterparts.

“He [Colonel Greene] would defend the Fort as long as he had a Man, & as to Mercy it was neither sought nor expected at their hands.”

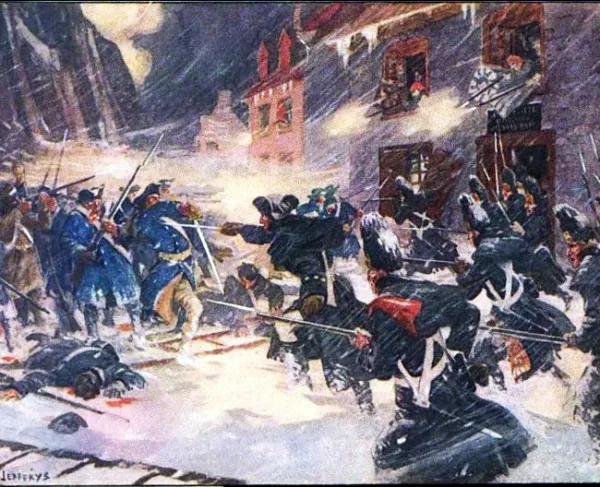

Captain Johann Ewald, a Hessian jaeger officer, remembered the American answer to be slightly different; “By God, no!” in his diary. With the niceties over, Donop moved his forces from the woods where they rested and shook his command into three columns. The leftmost column faced abatis due to the absence of pioneers with the column to clear their front. Donop rode the lines imploring his men to “aim low.” With that, the advance began, covering the approximately 400 yards of open terrain to the fort.

None of the three columns breached the walls of Fort Mercer. A few intrepid Hessians mounted the palisades but did not make it over. Even the British Navy struggled with their part of the action, as two of the ships ran aground trying to maneuver into position. The Hessians lost 371 men killed, wounded, or captured. One of the mortally wounded was Donop himself, who was struck in the thigh with a musket round. The attack lasted an entire 40 minutes.

Meanwhile the British crept ever closer to Fort Mifflin across the river. By November 10, the British had built fortifications to house armament as big as 32-pounders to hurl their missiles of destruction toward the Americans.

With the help of French engineering, the fort had made some alterations, including a redan to lend support to the main battery. In addition, flying over the ramparts was a flagpole made from a ship’s mast. Fluttering in the breeze was a flag designed by Mrs. Elizabeth Griscom Ross, better known to history as “Betsy Ross.” Under the flag was a garrison of approximately 450 men.

Starting on November 10, artillery fire rained back and forth, but the next day, a British artillery shell crashed through the barracks and struck Lt. Col. Smith in the left hip. Luckily for the officer, the shell was spent, but fallen bricks from the chimney and other debris caused a dislocated wrist. He was ferried across to New Jersey and command eventually fell to Major Simeon Thayer of the 2nd Rhode Island.

The bombardment continued unabated and by November 14, the British had constructed two further batteries adding more 32-pounders to the artillery aimed at Fort Mifflin. To add even more firepower, the British Navy moved ships within 20 yards of the American’s ramparts.

Thayer responded by repositioning the fort’s 32-pounder and also raised a distress signal flag to try and attract the attention of Commodore John Hazelwood in charge of a makeshift flotilla on the Delaware River. When the British interpreted this as a signal of the fort’s capitulation, American officers demanded the distress signal flag taken down and the “Betsy Ross” flag returned. Hazelwood’s ships were turned back by the more powerful British ships stationed around Fort Mifflin.

The fort’s fall came later that evening. Thayer surveyed the damage and destruction within the interior of the fort and the dipping of morale by the constant bombardment. He ordered the 300 survivors and whatever equipage could be saved to row across to Red Bank under the cover of darkness. Around midnight, the fort went up in flames and Thayer ensured he was the last out of the fort.

As the British entered the charred interior of Fort Mifflin on November 16, British General Lord Charles Cornwallis was preparing to embark on the second offensive against Fort Mercer in New Jersey. Two days later, on November 18, after Cornwallis’ landing, the American garrison destroyed the magazine within Fort Mercer and evacuated the post. Another two days later, Hazelwood scuttled his ships. The chevaux de frise had also been cut in two places by the British Navy when they became aware of the barrier.

With the forts, navy, and iron spikes removed, the British army in Philadelphia could be resupplied and supported by their counterparts in the British navy. The partial Siege of Philadelphia was over.

We can save three remarkable battlefield sites if we can raise $201,500. Every dollar you can donate to this cause will be multiplied by $23.80.

Related Battles

1,300

587

272

11

1,111

533