The Battle for Stony Point

Night raids always presented unforeseen dangers. Lunar and weather conditions usually determined the right evening to engage in an offensive strike. The best commanders thought out every possible scenario that could lead battle plans into uncharted waters and jeopardize the mission and the soldiers. General George Washington was not afraid to take risks under the cover of darkness. Whether it was the escape across the East River at the end of the Battle of Long Island in 1776 or the crossing of the Delaware River during the Trenton and Princeton victories later that year, the American commander of the Continental Army saw the value in using the elements to his army’s advantage.

This night, July 16, 1779, would decide the fate of a spit of rock that jutted out into the Hudson River thirty miles north of New York City. Though its size was seemingly insignificant, the positioning along the busy river at a critical narrow pass made its value imperative. Such was the battle between the American and British armies over control of the Hudson River itself. From the beginning of the war, British policy had been to isolate the rebellion in Massachusetts. When that failed, the next phase of their plan was to take New York City and block access to the Hudson River north of the city. From Canada, the British would sail naval detachments down the St. Lawrence River and link up with the forces in New York through a series of waterways and overland campaigns. Doing so would effectively cut off New England from the rest of the continent and hopefully contain the insurrectionists.

After nearly destroying Washington’s army at Long Island and then chasing him across New Jersey into Pennsylvania, it seemed inevitable the British would succeed in this strategy. They did not count on the resiliency of the Continental Army. Nor did they persist at key moments where the larger British forces would likely have crushed the smaller American ones. The British ended up with New York City as their North American headquarters and Philadelphia as their symbolic token of victory, but they had not defeated Washington and his army. The defeats at Saratoga under Horatio Gates in the early fall of 1777 further disrupted the imperial hold on the Hudson. The British army evacuated Philadelphia in May 1778 and the two clashed at Monmouth, New Jersey on June 28 which ended in a stalemate. Much of the remaining campaigning that year was reserved for smaller raids and skirmishes. Behind the scenes, the British commander in chief Sir Henry Clinton was busy dictating the new strategy heading into 1779. The overall shift towards the South would begin at some point in the hopes of rallying loyalist support, suppressing the rebel leadership, and then using the South to leverage the remaining pockets of resistance in the North. But Clinton was also keen to keep New York as the center of British operations, and the Hudson River Valley remained the main artery for distributing supplies throughout the continent. He was also determined to do what his predecessor had failed to do—lure Washington out of the northern hills of New Jersey into a major engagement.

Sir William Howe had come close to enticing Washington into a major battle. That was June 1777 in the short hills of New Jersey, but ultimately the American commander did not take the bait, and the British quit the state for the open sea. Now Clinton was hoping to bait the Americans out of their encampment at Middlebrook, New Jersey, the same mountainous foothold that had served them well before. Clinton’s overall plan called for British raids in Virginia to entice local officials to ground militia they might have been planning to send north to reinforce Washington. These occurred in May. In early June, Clinton then struck his main assault up the Hudson. He divided two forces on either side of the river to attack the points of Stony Point and Verplanck’s Point; each was the landing for the Kings Ferry, a crucial transport that provided access to much of the upper Hudson Highlands. It was there Clinton assumed Washington would be waiting, and where the British commander could hopefully lure him down into battle.

Indeed, Washington had moved from Middlebrook to the Hudson Highlands by June. Like the British, the Americans had assembled on both sides further up of the Hudson near the American fort of West Point. Washington considered the fort to be his anchor for holding the entire river. He also correctly assumed that Clinton’s movements meant two things: the British were either planning a major assault on West Point or were trying to bait his army out of the hills.

The British had taken Stony Point with no resistance. Only about three dozen or so Americans were guarding a blockhouse when British ships appeared on the horizon. The Americans promptly destroyed what breastworks there were, set fire to the blockhouse, and abandoned the area. On June 1, a battery had been assembled. British Maj. Gen. James Pattison, who would soon become commandant of New York, assisted Clinton and led the fortifying of Stony Point. To beef up the British redoubt, he instructed that, “The Guns intended for these Works are two 24 Prs (pounders) and two 18 Prs, four 12 Prs, six 6 Prs, and one 3 Pr, one 10 Inch Mortar, one 8 Inch Howitzer, two Royal Mortars, and two Cohorns….” Stony Point’s peak reached about one hundred fifty feet above the river. The British guns opened fire on the Americans across the river at Verplanck’s Point. After a brief shelling, once again, the small forces abandoned the second point only to be captured by British Maj. Gen. John Vaughn’s army approaching from Taller’s Point south. Clinton’s plan of splitting his forces along the river had successfully captured both objectives.

Initially, Washington responded by ordering Maj. Gen. Alexander McDougall to call forward the six brigades under his command while sending word to New York Governor George Clinton, who soon arrived to command the New York militia at nearby Fishkill. McDougall held West Point while Governor Clinton was positioned directly across the river to the east. Washington did not want to relocate from the Highlands. He moved the main body of the Continental Army to Smith’s Cove, about ten miles from Stony Point, still out of reach for a major engagement. He was simply preparing for what northern move Clinton tried next. But Clinton was not prepared to further his advance up the river. Instead, with about one thousand soldiers at Stony Point and another five thousand at Verplanck’s Point, the British commander set in motion his real intentions for taking the positions.

On July 5, British Maj. Gen. William Tyron landed in Connecticut with a force that soon marched on New Haven and put down the initial militia defense. They burned several villages and towns on their pillage. Governor Jonathan Trumball called up further militia and dispatched a request to Washington for reinforcements. Several detachments were already in motion to support Connecticut and the militia eventually assembled in force to push out Tyron’s army. Washington, however, suspected the raids were a diversion, and never once budged from the Highlands. Instead, he had already planned his next strike: he would attack Stony and Verplanck’s points.

On July 1, Washington had called for an assault on both sides of the river. The British had weakened their manpower by this point, and each side was now lightly defended in comparison to a week before. In truth, Clinton kept removing troops to either his position south at Kingsbridge, NY, further south to Manhattan or east to Connecticut. Intelligence had been gathered by Delaware captain Allen McLane confirming the weakening of the garrisons. By now, there were only about six hundred or so British troops posted at Stony Point; a mixture of the 17th Regiment (with Lt. Col. Henry Johnson in command of the garrison), two companies of the 71st Grenadiers and loyalists, and a detachment of mixed Artillery. The sloop Vulture was anchored in the river to keep guard of the access points. If Washington could retake the terminals on either side of the Hudson, he could eliminate the encroachment Clinton had initiated towards West Point.

Brigadier General Anthony Wayne was in Pennsylvania at the time. The commander was a well-liked field officer and showed bravery that Washington admired. Wayne’s reputation had taken a hit after forces under his command were surprised at Paoli in October 1777, resulting in heavy losses and the lore that the British had bayoneted Americans against screams for mercy and quarter. The British did attack in the stealth of night using the bayonet to great effect, but the Americans had blundered by alerting the enemy to their position by their campfires and musket flashes. Wayne was cleared with any wrongdoing, but when he was passed over for promotion by rival Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair, Wayne considered resigning. Instead, he asked for time off which Washington granted. On June 26, Wayne received a letter from the American commander in chief. Wayne had campaigned for the command of a new special light infantry unit Washington was assembling for covert operations in the coming weeks. Washington instructed Wayne to return to camp immediately. The assault on Stony Point would be the first test of this new fighting unit.

The brigadier arrived on July 1 and took command of the planning at once. Training began at Fort Montgomery and the parade ground at West Point for the roughly thirteen hundred soldiers picked to lead the attack. Baron von Steuben, the colorful drillmaster of Valley Forge fame, assisted in the critical instruction. Both Washington and Wayne spied the British works on Stony Point from nearby Dunderberg Mountain. The British had felled trees, creating abatis around much of the peninsula. But they had left a portion of it exposed along the southern corridor where a narrow beachhead formed at low tide. Days of reconnaissance by several American officers kept a watchful eye on the enemy garrison. Legend has it Wayne told Washington he would “storm hell if you would plan it” as they discussed the practicality of a daytime assault. It was ultimately decided a nighttime raid would be more effective. Changes were made and a plan was formed.

On July 10, the details were worked out. The assault on Stony Point would be divided between three groups. One would lead the main attack by marching past Stony Point and then, crossing a low tidal swamp, come ashore on the narrow beachhead. This group would be armed with bayonets and spontoons, only. A second group would provide a demonstration along the main causeway, drawing the attention of the battery away from the main assault. And a third would advance from the north at the sound of the first enemy musket fire, assumed to be on the American southern wing. The plan would be to envelop the garrison before it had time to mount any type of defense. As this was happening, a second force on the other side of the river would approach the British garrison at Verplanck’s Point and await the capture of Stony Point before moving to assault their target. Wayne was given leeway to alter the battle plans in real-time as he saw fit, a testament to the trust Washington had in him.

On July 14, Wayne met with the officers who would be commanding the three columns that would assault the garrison. Col. Christian Febiger was commanding the assaulting column that planned to wade through the low tidal zone and attack from the south. Col. Richard Butler’s column would simultaneously approach from the north, cutting through whatever defenses lay in their path and meet Febiger in the garrison. Major Hardy Murfree would then lead the third column from the west over the inland causeway, having created a diversionary fire that hopefully convinced the British that the main assault was coming from them. The remainder of the army would not be told of their plans until the last minute. The men assembled on Sandy Beach along the river and were instructed to shave, powder their hair and ensure provisions were sufficient.

The following day July 15, at noon, Wayne left Fort Montgomery with thirteen hundred American troops under his command. The soldiers marched along a narrow trail to the west of Bear and West Mountains. They paused mid-afternoon on the Clement farm to rest, but no soldier was allowed to leave his column unless in the presence of an officer. By eight that evening they arrived at the farm of David Springsteel, about a mile or so away from their target. The soldiers were now told what their objective was. The commanding officers divided their men into three columns; portions of two regiments would attack from the southern shoreline while a third would attack from the northern shoreline. The remaining battalion would lead the diversionary assault on the causeway. A selection of about one hundred fifty men were then instructed to be the advanced assaulting force armed with pickaxes. An additional forty men were divided between Febiger and Butler’s columns who would be known as ‘forlorn hope,’ the name given to those who primarily would be doing the hand-digging and clearing that was needed to pull it all off. The men under Febiger were instructed to unload their muskets. Timing was everything and strict instructions were given that any soldier who broke silence or who fired a loaded musket during the approach would be shot dead on the spot.

As the moment approached, a sense of patriotism filled the ranks. Two junior officers successfully fought for command of two of the columns. Wayne would march with Febiger on the southern assault. To entice his men, he offered a bounty of $500 to whoever would brave the breastworks first. The soldiers were then given pieces of white paper to place in their caps to identify each other. The general had written to a friend that he feared leaving his wife a widow. It was clear to him that this mission would likely come at a great cost.

In the meantime, the British were confident Stony Point was properly fortified and armed to repel any attack. The point had been nicknamed “Little Gibraltar” by some in New York. Clinton was confident that any move Washington made would be intercepted and provoked into a major engagement. He readily awaited, assuming he was right.

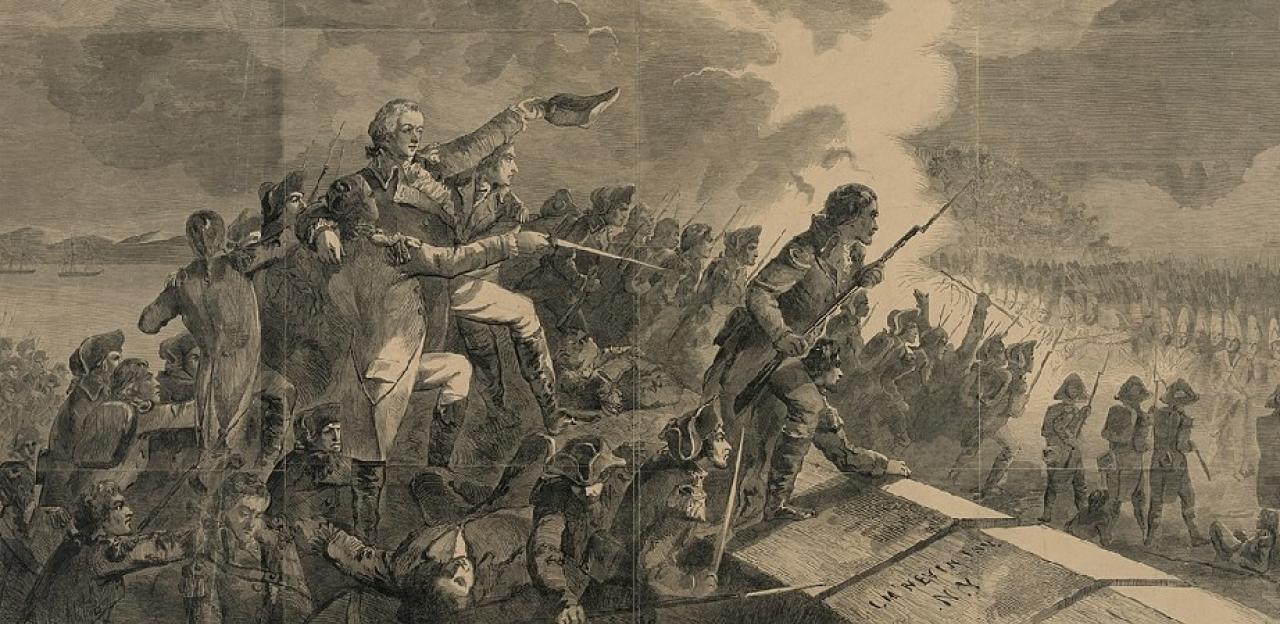

About 11:30 pm, Wayne looked at his column and said, “Forward.” The assault was on. Febiger’s men moved south past the peninsula and then found the river’s edge. Wayne gave the order to attack just before 12:30 am on July 16. However, the American general found their pathway was now submerged underwater. The Americans proceeded in the chest-high water. As they waded, a British sentry spotted the enemy soldiers approaching and alerted the garrison. The Americans hurried now under fire and reached the narrow shoreline, finding abatis wrapped around some portions of the defenses. The forlorn hope men rushed forward with their pickaxes and hacked away the debris. British troops continued firing on the Americans. Seventeen of these ax men fell, but the group had cleared enough of the abatis for the column to storm the breastworks. Lieutenant Colonel Fleury was the first American over the top. In the melee, Wayne was struck in the head by a musket ball. Toppling over and losing his cap, he ordered his soldiers to march onward. They did so armed with bayonet and struck mercilessly as the column broke through the defenses. Not knowing the damage inflicted, Wayne then asked his subordinates to carry him into the fort so that he could die among his men in the heat of battle. The ball had just grazed him, luckily, and he would recover in the following days.

Meanwhile, the sound of muskets alerted Murfree’s column approaching west along the causeway. Immediately, they rushed forward firing their muskets. The startled redcoats tried to set up a line of defense. But as they did, Butler’s column, who had heard the initial sentry firing on Wayne’s men, and successfully cut through the abatis, attacked from the northern side of the garrison. British troops began throwing down their arms and screaming for mercy and quarter. The Americans, in return, hollered the watch phrase, “The Fort is ours!” Butler’s men poured into the breastworks. It was over. Fleury lowered the British standard. Stony Point had been taken in less than half an hour. The Americans suffered about one hundred losses to the British one hundred and fifty.

Wayne quickly sent off word to Washington that, “This fort & Garrison with Coln. Johnson are our’s. Our Officers & Men behaved like men who are determined to be free.” The Americans had taken roughly five hundred or so prisoners, (“Almost the whole of the 17th Regt, two Companys of the 71st, about sixty of the Loyal American Corps…,” according to British Gen. Pattison), with a Lieutenant Roberts swimming to shore and then to safety aboard the Vulture. With the remaining British now captive, the Americans turned the enemy cannon against the Vulture in the river, and on the second British position over half a mile across the Hudson at Verplanck’s Point. American Col. Rufus Putnam had been ordered to create a feint on the Verplanck side of the river as Wayne led his assault. This would eventually give way to reinforcements under the command of Maj. Gen. Robert Howe. But their plans to score a second victory were dashed when Sir Henry Clinton sent Brig. Gen. Thomas Stirling with three regiments up the river to intercept another American assault. Howe would linger until the 18th before retreating at the sight of the advancing British forces. Meanwhile, the remaining Americans on Stony Point removed everything the British had thrown up for defenses, along with seizing fifteen cannons and other provisions. Washington personally oversaw these operations before returning to West Point on July 19.

Stony Point would be reoccupied by the British in a matter of days of them losing it in the early hours of July 16. For the Americans, the loss of the ground might seem counterproductive. Why risk soldiers over a spit of land that was never intended to be held? The truth is Washington did hope to obtain both Stony and Verplanck’s points, but he was not foolish enough to risk a sizable portion of his army to do so. The only way to defend the river would be to give up the Hudson Highlands, which is precisely what Clinton hoped would happen. But Washington had no intention of ever doing so if it risked too much. Instead, he continued to fortify West Point to the north and remained deceptively out of reach from the British commander. As for Clinton, any hopes of a new campaign would now have to wait. Privately, he admitted the whole operation along the river had been a failure, and the moves to Connecticut had lost him time, supplies, and soldiers. None of his actions had produced Washington on the battlefield.

The quick and decisive victory would do much to repair the reputation of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne. Fellow American general Nathanael Greene said the victory, “for ever immortalized Gen. Wayne, as it would do honor to the first general in Europe.” The treatment of the captured troops was reported among the officer corps back in New York. Pattison wrote of Wayne on July 26, “It must be in Justice be allow’d to his Credit, as well as to all Acting under his Orders, that no Instance of Inhumanity was shown to any of the unhappy Captives.” Fellow American Benjamin Rush summed up Wayne’s exploits with, “You have established the national character of our Country. You have taught our enemies, that bravery, humanity and magnanimity are the national virtues of the Americans.”

Despite the success of the attack, and the site’s abandonment to only be recaptured by the British, the assault’s greatest legacy is what Wayne did not do: he did not avenge Paoli or stoop to barbaric cruelty towards his British captives. Wayne’s intentions were not to seek revenge. The conduct of his soldiers put this to rest. The assault was a well-coordinated attack on a fixed position that benefited from Washington’s planning of dividing his forces into three. The decision to strike at night rather than during the day added to the mission’s success. Wayne’s men faced the most enemy fire, but it was the other two American columns who emerged in the rear that ultimately swung the assault into confusion and defeat for the British. It was near-perfectly executed. General Wayne earned the glory in victory.

The Stony Point Battlefield has been historically recognized since 1961 and currently allows tours that show numerous historical artifacts including the original British fortifications.

Further Reading

-

George Washington’s Generals and Opponents: Their Exploits and Leadership: By George Athan Billias

-

Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolution Through British Eyes: By Christopher Hibbert

-

Washington’s Partisan War: 1775-1783: By Mark V. Kwasny

-

General George Washington: A Military Life: By Edward G. Lengel

-

The New York Historical Society Collection of 1875: By James Pattison & Lewis Morris

-

The Unsuccessful American Attempt on Verplanck Point, July 16-19, 1779: By Michael J. F. Sheehan

-

Anthony Wayne: By John R. Spears

-

The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution: By Alex Storozynski