"They Was In There Sure Enough"

By Douglas R. Cubbison

Spring Hill, Tennessee, saw periodic action throughout the Civil War. In November 1864 the small hamlet became a strategic target for two enemy armies engaged in a deadly race.

In 1861, Spring Hill was a small Tennessee town located halfway between Columbia and Franklin on the old National Road. The businesses and farms of the community were dominated by the imposing mansions of wealthy planters, places with romantic names like Ferguson Hall, White Hall, Rippavilla, and Oak Lawn.

In the winter of 1862 war came to Spring Hill when a jaunty, handsome general from Mississippi by the name of Earl Van Dorn led his mounted cavaliers into the region. They had just destroyed a Union supply depot at Holly Springs. Mississippi and the troopers were to spend the winter camped around Spring Hill.

On March 5, 1863, a Federal reconnaissance column left from Franklin in the direction of Spring Hill. The Union command unwisely marched beyond range of its supporting forces, and encountered Van Dorn's aggressive cavalry at Thompson's Station. After a rough fight, the Federals ran out of ammunition and were forced to surrender to the Confederate general. Van Dorn lost only 351 men while inflicting casualties of 48 killed. 247 wounded and 1,151 captured. It was his finest moment as an officer.

Allegedly, Van Dorn chose to celebrate this victory in the arms of "a young and handsome" woman named Jessie McKissick Peters. It was rumored that Jessie was "often seen with Gen. Van Dorn and other dashing young officers on their fine horses." On May 7, 1863, her husband, Dr. Peters, called on General Van Dorn at his headquarters at Ferguson Hall. The private interview terminated abruptly when Dr. Peters fatally shot Van Dorn.

Late in the summer of 1863, Federal forces occupied Spring Hill and established a small garrison to protect the railroad that ran through the town. In the process they set up a line of couriers between other Federal posts and Nashville. Spring Hill remained a backwater of the conflict until November 1864, when Confederate General John Bell Hood brought the war back to the small town.

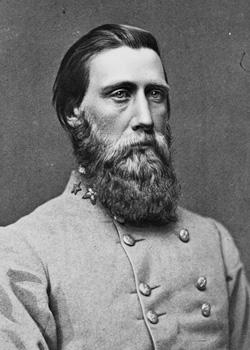

Hood was born at Owingsville, Kentucky, on June 1, 1832. He graduated from West Point in 1853 without distinction, ranked 44 out of 52 cadets. As a young officer in the Regular Army, Hood earned distinction as a brave and determined fighter, but he was also known as an impetuous risk taker. After the South seceded, Hood resigned his commission to become a colonel in the Confederate States Army.

Leading a brigade of Texans, Hood broke through a strong Federal position during the Seven Days Battles and began building his reputation as a hard-charging leader. While commanding a division at Gettysburg, Hood sustained an injury that crippled his left arm. Barely three months later, he lost his right leg at Chickamauga. His wounds scarcely healed, Hood was back in action at the onset of the Atlanta Campaign in May 1864. Though his is performance as a corps commander was less than stellar, Confederate President Jefferson Davis eagerly turned to Hood, hoping his fighting nature could save Atlanta.

And Hood did fight. Eight days of brutal combat in late July left the Army of Tennessee devastated. Typical of the experiences of that army was the 45th Alabama Infantry, which on July 22, 1864, had 200 fighting men. By the end of the day, only 80 men remained fit to serve. On July 28, several Confederate columns refused to assault at Ezra Church, a first for the proud army. Sherman easily outmaneuvered Hood in late August, and Atlanta was evacuated on September 1.

Hard marches and occasional hard fighting in late September and October failed to draw Sherman out of Atlanta. As a result, Hood's subsequent operations in middle Tennessee were born from his inability to save Atlanta after a summer of fighting, or regain it through autumn maneuvers.

Hood crossed back into Tennessee with approximately 30,000 infantry, 124 guns, and 6,000 cavalry commanded by Nathan Bedford Forrest. Heavy rains that swelled the Tennessee River, a dismal supply situation, and a tenacious Union defense at Decatur, Alabama, delayed the crossing.

Once over the river, Hood intended to interpose his army between the 30,000 Union soldiers of Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield's IV and XXIII Army Corps, located at Pulaski, Tennessee, and the roughly 30,000 man garrison at Nashville under Schofield's superior, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas. Hood was confident that he could defeat the two Federal forces independently, and capture the massive Northern supply depot at Nashville. With dual victories to bolster his reputation, and with his army re-armed and re-equipped at Union expense, Hood could continue the offensive into Kentucky and Ohio. Hood surmised that an incursion into Federal territory would result in a Confederate resurgence and a Northern panic, diverting resources from the siege of Petersburg, and prompting a recall of Sherman's forces from Georgia. It was a bold, risky plan, and it reflected Hood's courageous and gambling personality.

Hood's initial series of maneuvers forced Schofield to retreat from Pulaski to Columbia. Encouraged by the first steps of the campaign, the Confederate general determined to march his army around Schofield's flank and seize the turnpike in Schofield's rear at Spring Hill. Forrest's cavalry led the way and crossed the Duck River at Huey's Mill on November 28. In a series of brilliant feints and fights, Forrest drove the Union cavalry away from Schofield, effectively removing the Yankee horsemen from the scene. Having accomplished this, Forrest set his sights for Spring Hill.

Leaving one corps and the bulk of his artillery on the south bank of the Duck River to hold Schofield's attention at Columbia, Hood's remaining two corps marched east to cross the Duck River at Davis Ford, three miles east of Spring Hill. Once across the river he began a rapid march to Spring Hill on the Davis Ford Road, a badly rutted country lane abandoned even by local farmers.

Although Hood had the lead in what would become known as the "Spring Hill Races," he had not completely deceived Schofield. Upon receiving reports that Hood's infantry was crossing the Tennessee River, Schofield telegraphed Thomas and received orders to withdraw to Franklin to protect the Harpeth River crossings there. Schofield started his withdrawal by sending his 800 wagons and most of his artillery up the Columbia-Franklin Pike with a guard of Brig. Gen. George Wagner's division, the whole under the command of IV Corps commander Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley.

Early in the afternoon the lead elements of Wagner's division began entering Spring Hill from the south, and established a strong defensive position under Stanley's direct supervision. Colonel Emerson Opdycke's brigade moved through the town to occupy a ridge just to the north. Colonel John Lane's brigade continued Opdycke's line east of town. Brigadier General Luther Bradley's brigade assumed a critical location on a knoll south of town. The 103rd Ohio Infantry and a section of Battery A, 1st Ohio Light Artillery were placed across the Columbia—Franklin Pike. Eighteen artillery pieces were placed on a prominent ridge on the southern outskirts of the town.

In the meantime Forrest's cavalry aggressively moved toward Spring Hill. The small Union garrison, strengthened by other units in the vicinity, put up a spirited resistance south and east of town. Many of the Union defenders were armed with repeating rifles, while Forrest's men had been in the saddle fighting for nearly 48 hours, their horses were jaded, and they were low on ammunition. Forrest could only slowly push the Federals back toward Spring Hill.

As Stanley moved his regiments into their positions, Forrest determined to make an attempt to seize Spring Hill. He turned to the brigade of Brig. Gen. James Chalmers. Chalmers balked, suggesting that there were strong Federal forces to his front. Forrest assured him that his men could easily brush aside any slight Union resistance there might be. Chalmers' men moved forward, only to have a volcano of gunfire explode in their face. The horsemen were easily repulsed sustaining heavy casualties. Forrest turned to Chalmers and remarked, "They was in there sure enough, wasn't they?"

Major General Patrick Cleburne's Division of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Cheatham's Corps led the advance, and Hood gave them definitive orders to cooperate with Forrest's cavalry, and "take possession of and hold that pike at or near Spring Hill." Cleburne's Division moved west from the Rally Hill Pike at 4:00 p.m. to seize the Columbia-Franklin Pike. Cresting a large hill immediately west of the pike, Cleburne crossed a light strip of woods and moved into an open field. His line of march was across the front of Bradley's brigade, which soon raked Cleburne's exposed right flank belonging to Brig. Gen. Mark Lowrey's Brigade with a "destructive fire."

Lowrey was stunned by Bradley's volleys, but many of Bradley's men were in their first fight, and opposing them were hardened Confederate veterans who were arguably among the toughest fighters in an army of fighters. Cleburne snapped, "I'll flank them," and ordered Brig. Gens. Daniel Govan and Hiram Granbury to wheel their brigades and come on line with Lowrey. Cleburne's entire division moved forward en masse—the result was inevitable.

Cleburne's advance rolled north in pursuit of Bradley's retreating brigade, which fled to establish new lines at the southern edge of town near Van Dorn's old headquarters of Ferguson Hall.

Cleburne's pursuit was brought to a halt by staggering volleys from the artillery and the 103rd Ohio Infantry positioned across the Columbia-Franklin Pike. Cleburne's veterans pulled up short and sought cover under an intense and accurate barrage from the well positioned Union field pieces. It was now nearly 5:00 p.m., sunlight had faded into sunset, and Cleburne had run into unexpectedly heavy opposition. He called for support and instructions.

During the march north on the rutted and muddy roads, Hood's horse had slipped and fallen on his amputated leg. In great pain, he established his headquarters at Oak Lawn, near the Rally Hill Pike. Hood spent most of the battle sitting sick on a log near a fish pond, out of sight of Cleburne's attack. Hood then went to bed early, apparently confident that Forrest held the pike north of Spring Hill, and thus was not unduly concerned with cutting the pike south of town. In fact, he told one soldier at headquarters that Schofield was trapped, and would surrender in the morning.

Confederate divisions maneuvered blindly in the darkness, attempting to respond to confusing orders from Cheatham and Hood. Hood's soldiers had not eaten since before daybreak, and they were exhausted from the long march over horrid roads. Following a number of fitful attempts at continuing their advance, the entire Confederate army sat down for the night, cooked supper, and went to sleep. Forrest made a feeble attempt late that evening to cut the pike north of Spring Hill at Thompson's Station, but the appearance of strong columns of Federal infantry rapidly cleared the road.

While the Confederates rested on their laurels, real or imagined, the Federal army performed a well-planned and well-executed retreat. Schofield and his subordinates made their headquarters in the saddle, and issued clear, certain instructions. All that evening and past midnight, the Federal wagons, artillery, and long columns of infantry marched toward Franklin on the dark macadam road. By dawn the last blue-clad soldiers had marched north from Spring Hill.

The Union army had escaped. General David Stanley would remember:

"The repulse of the Rebels at 12 o'clock noon, and again defeating them at dusk hi the evening with a force not exceeding four thousand infantry, kept Schofield's road open for retreat, saved the army, and was the biggest day's work I ever accomplished for the United States."

The next morning found Schofield's army at Franklin, digging in to cover the Harpeth River crossings. John Bell Hood awoke to discover that the Union army had slipped away, and he was infuriated. A Confederate staff officer wrote of Hood, "He is as wrathy as a rattlesnake this morning, striking at everything." In a morning breakfast at Rippavilla Plantation, Hood lashed out at his commanders, heaping abuse upon them and condemning their failures in unmistakable language.

Late that afternoon, Hood, out of options, launched his army at the Federal fortifications at Franklin in a desperate, last roll-of-the dice assault. It failed with devastating casualties. After Franklin, the Army of Tennessee no longer existed as a viable fighting force. Two weeks later Thomas would move upon Hood's shattered army south of Nashville and destroy it. The roots of the destruction of the Army of Tennessee at Franklin and Nashville can be traced directly to Hood's failure at Spring Hill on the afternoon of November 29, 1864.

DOUGLAS R. CUBBISON, a graduate of Indiana University of Pennsylvania, has written numerous articles on the American Civil War and presentation plans for APCWS. He is the Site Manager at Ohio Village in Columbus.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...