The American Civil War has been classified by some historians as a “total war." Total war is defined as “a war that is unrestricted in terms of the weapons used, the territory or combatants involved, or the objectives pursued.” The war was not only fought on distant battlefields in which soldiers remained widely separated from the rest of the population. It was also fought on peoples’ farms and in towns, where civilians were forced to experience the war first-hand, especially throughout the South.

The Confederacy mobilized large numbers of men into the army, leaving many White women and children to fend for themselves, many ultimately becoming widows or orphans by the war’s end. In the countryside, armies destroyed or appropriated property, seized food, burned fences, and turned houses into hospitals. While this short essay will focus on the effects of the Civil War on the White population throughout the South, African Americans were also impacted by the war. Free and enslaved Blacks were separated from their families to labor for the army and free Blacks saw their freedom further restricted as White southerners questioned their loyalty to the Confederacy. The effects of the Civil War on African Americans are covered in a different article.

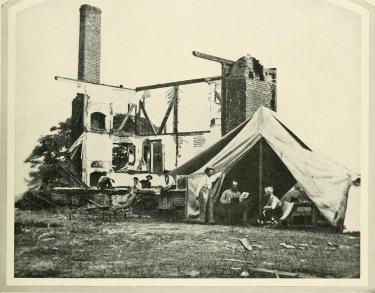

Some of the most immediate effects during the Civil War were seen in food shortages and property damage. As early as 1861 with the First Battle of Manassas civilian’s property was damaged. Homes were destroyed not only during battle, but from the subsequent encampments in which soldiers needed living quarters, firewood, and food. One of the most famous examples of property being damaged at the beginning of the war is Judith Henry’s house located on a prominent portion of the Manassas (Bull Run) battlefield. On July 21, 1861, the home was located between Union and Confederate lines, changing hands multiple times during the fighting. Over the course of the battle, Confederate sharpshooters used the upstairs rooms for cover and an elevated firing platform. Major General James Ricketts ordered the house shelled by nearby Federal artillery to drive the sharpshooters away. Unbeknownst to Ricketts, he did not know that Judith Henry was still inside, bedridden and refusing to be removed from her home. Over the course of the battle, a shell finally burst through the ceiling of Judith’s room and exploded resulting in “the bed on which Mrs. Henry lay was shattered, she was thrown to the floor, being wounded in the neck, side, and one foot partly blown off. She died later that afternoon or early evening.”

Battles were not the only time when families experienced property damage. After most fights, many of the nearest homes were commandeered as hospitals, headquarters, or encampments. Shortly after the Battle of First Manassas, homes and other farming buildings were quickly taken over leading to property damage as blood ran on the floors, personal property was used by medical personnel and yards became burial grounds. Fannie Ricketts described the scene at one hospital at Portici at Manassas when she wrote, “downstairs there are some forty men in various stages of death or possible recovery. Blood runs on the floor, the smell is dreadful, but no language can describe it…” Not only was personal property taken for use in hospitals, but during encampments or when soldiers were just passing through. When firewood became scarce in the wintertime, fences were quickly taken down and burned. After the fencing was gone wood paneling from walls went into flames and even bricks were removed to build chimneys.

Personal property from animals, foods, supplies, furniture, and more were also commandeered by both armies. At the end of the Civil War, thousands of claims for property damage against the U.S. Army were submitted to the Southern Claims Commission for reimbursement. Claimants had to prove continued loyalty to the United States throughout the war, resulting in few claims being approved by the commission.

The most pressing problem for many civilians in the Confederacy was the threat of starvation. Food shortages throughout the south stemmed from many sources including a drought in 1862 that drove down food supplies, a reduced workforce on farms and plantations as enslaved people fled to Union lines, and Federal troops gaining control of more parts of the Confederacy. Since the Confederate army had priority in terms of transportation, what little food was earmarked for civilians often went bad before it could be shipped from warehouses. When the government tried to rectify the situation by impressing food, farmers responded by hiding their crops and livestock. Hyperinflation sent the price of food skyrocketing while the value of the Confederate dollar cratered. Soon, food riots broke out in several cities, including the Confederacy’s capital at Richmond. Over the course of the “Richmond Bread Riots” in April 1863, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered the militia to open fire on several hundred women if they did not go home. Fortunately, bloodshed was adverted when the women finally went home. By the end of 1863, the cost of flour in Lynchburg, Virginia rose to $275 a barrel. Civilians had to find substitutes for items such as coffee, sugar, meat, or go without. As a result of food shortages over the course of the Civil War, families were forced to make ends meet any way they could. Towards the end of the Siege in Vicksburg, Mississippi, when sources of food outside the city were cut off, Dorra Miller recounted in her diary:

I am so tired of corn-bread, which I never liked, which I eat it with tears in my eyes. We are lucky to get a quart of milk daily from a family near who have a cow they hourly expect to be killed. I send five dollars to market each morning, and it buys a small piece of mule-meat. Rice and milk is my main food; I can’t eat the mule-meat. We boil the rice and eat it cold with milk for supper. Martha runs the gauntlet to buy the meat and milk once a day in a perfect terror.

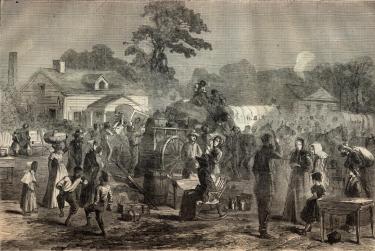

When conditions became too dangerous, many families throughout the Confederacy were forced to leave their homes to find safety as refugees. The decision to leave home and give up one’s home and the ease of knowing where food and shelter were was not one taken likely. Many refugees over the course of the Civil War left their homes out of extreme fear or distaste for the Union Army. All throughout the Confederacy, newspapers, and rumors spread alarming notions of what might happen when the Union Army arrived. When Fort Donelson fell in February 1862 and the Cumberland River was opened to the Union Army, Nashville was in a panic. One spectator wrote that Nashville “became perfectly paralyzed… panic stricken” and local newspapers reported that the panic “had never been equaled since Bull Run…all who could do so packed up and fled…”

The same panic occurred in Richmond in 1862 when the city was threatened during the Seven Days Campaign. When Port Royal, off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, was captured hundreds of residents from the nearby islands fled to Charleston, including one eighty-five-year-old woman who hadn’t made the trip in over fourteen years “for fear the trip would kill her, but was now willing to tempt fate when the Yankees were abroad in the land.”

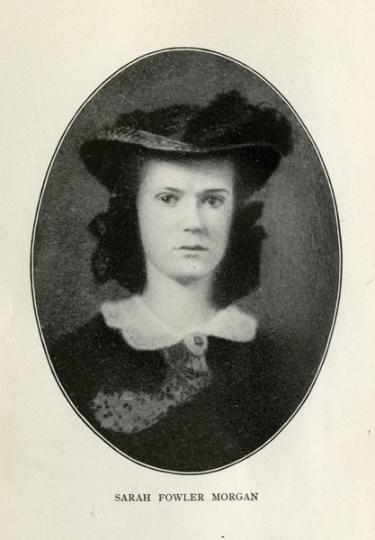

Others held such a disdain for the Union Army that after fleeing their homes they refused to return to Union held territory unless absolutely necessary. After wandering Louisiana for months, Sarah Morgan was forced to make the decision to stay a refugee or stay with her brother in New Orleans, she was so averse to the thought that she reflected in her journal:

Whether tis nobler in the Confederacy to suffer the pans of unappeasable hunger and never-ending trouble, or to take passage to a Yankee port, and there remaining, end them. Which is best? I am so near daft that I cannot pretend to say; I only know that I shudder at the thought of going to New Orleans.

There were several reasons that families of men, women, and children left their homes besides fear or hatred of the Union army. The threat of conscription, fire, disease, and many other circumstances forced many out of their homes. However, in many cases, leaving home was a risky and expensive endeavor and not everyone had the luxury to do so.

As soon as people decided to leave their homes, they were confronted with numerous other challenges that would affect their decisions. How would they get away? Where would they go? What would they take with them? What would they do with the possessions they couldn’t take? Because of these questions and more, the majority of those who left homes over the course of the Civil War were upper-class families with the network and the means to travel. Especially towards the latter part of the war, as the Federals progressed into the Confederacy, shortages of transportation, food, made the option of fleeing less and less available to the general population.

One Tennessee refugee, Mrs. McDonald, remarked “during most of the war, and always in areas being evacuated, everything that had wheels was in demand and even a cart was deemed a prize.” People took every mode of transportation available from “every conceivable style of conveyance, drawn by horses, mules, oxen and even a single steer or cow.” Trains were another source of travel for those who tried to flee for safety. One soldier remarked seeing a train passing through eastern Tennessee full of passengers and that “seats, aisles, platforms, baggage cars…and tops of cards were covered with passengers… and thousands had been left at the depot begging to come.” Prior to the fall of Atlanta in 1864 trains were flooded with refugees trying to get out of the city. One train was estimated to have approximately 1,000 passengers and “people who could not get inside were hanging on wherever they could find a sticking place; the aisles and platform down to the last step were full of people clinging… like bees swarming around the hive.” Walking was another option. Diarist Sarah Morgan remarked one overcrowded roadway outside of Baton Rouge, Louisiana:

Three miles from town we began to overtake the fugitives. Hundreds of women and children were walking along, some bareheaded and in all costumes. Little girls of twelve and fourteen were wandering on alone. I called to one I knew and asked her where her mother was; she didn't know; she would walk on until she found out...it was a heart-rending scene. Women searching for their babies along the road, where they had been lost; others sitting in the dust crying and wringing their hands.

With the reduced availability of transportation, the cost of using the trains or finding a cart became increasingly high. In 1863, Jorantha Semmes and her relatives were only able to move from Mississippi to Gainesville, Alabama by purchasing horses for between $500-$1,000 apiece. Another Louisiana family was able to rent a horse and buggy to travel four miles for $3,000.

Fear, uncertainty, and deprivation was a common feeling for Civil War refugees. Forced to abandon their homes as occupying forces approached, civilians fled with limited household goods and only modest amounts of clothing and personal items. Forced to leave Memphis with only 24 hour’s notice, Elizabeth Merriwether put into words what many families were feeling during the war:

I seemed all of a sudden to realize the desolateness of my position, alone in the world with two children, driven from pillar to post, my husband off in the army, I knew not where - surely it was a pitiable situation. I became filled with self-pity and cried as if my heart would break.

When they returned, they were greeted with destroyed crops, ransacked homes, and beleaguered communities. Called a "nation of nomads," 175,000 to 200,000 Confederate sympathizers were on the move during the war, the largest wartime flight in U.S. history.

Further Reading

- Sarah Morgan: The Civil War Diary of a Southern Woman By: Charles East

- Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War By: Drew Gilpin Faust

- Diary of a Southern Refugee during the War by a Lady of Virginia By: Judith W. McGuire

- Refugee Life in the Confederacy By: Mary Elizabeth Massey

- Driven from Home: North Carolina's Civil War Refugee Crisis By: David Silkenat