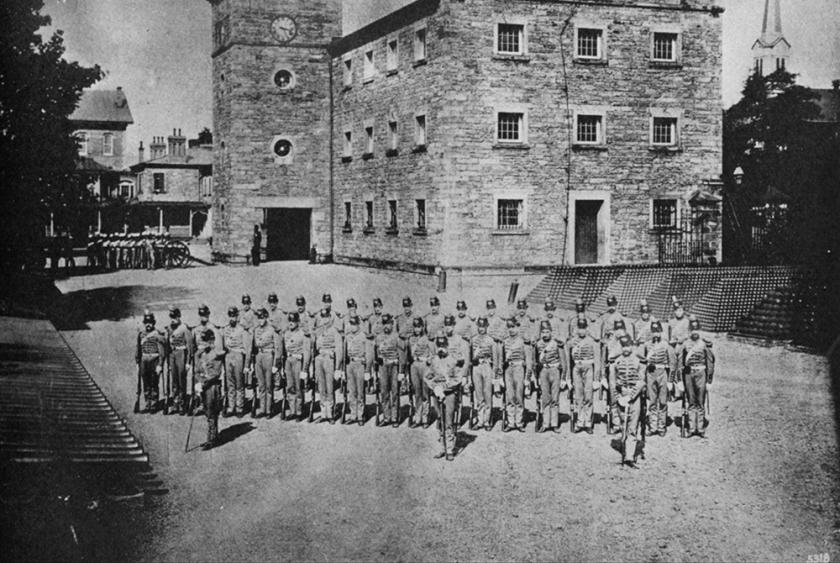

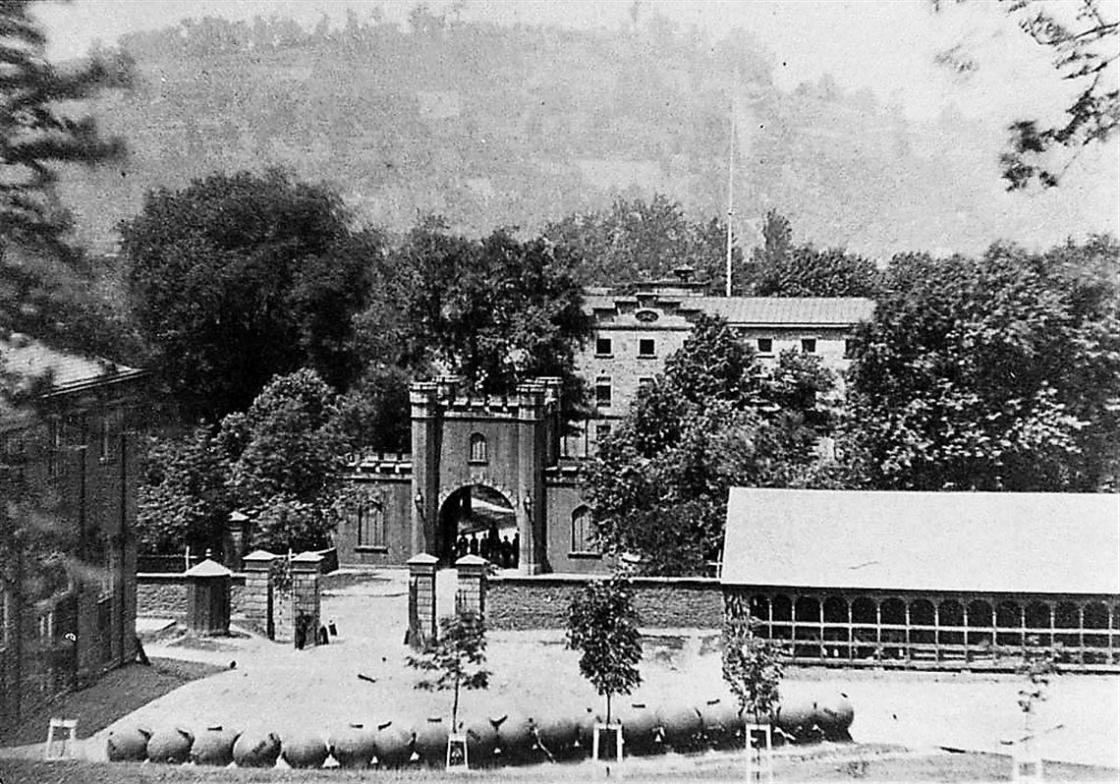

Allegheny Arsenal. Lawrenceville, Pa.

As if by some strange and violent coincidence, Wednesday, September 17, 1862, is a date synonymous with death and tragedy. While most remember this day for the bloody fight along Antietam Creek, the Western Pennsylvania community of Lawrenceville recalls a tragic event which unfolded nearly 200 miles from the battlefield. On the outskirts of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a series of three explosions claimed the lives of 78 workers at Lawrenceville’s Allegheny Arsenal in what would come to be remembered as the largest industrial disaster of the American Civil War. While local papers recalled scenes that conjured up warlike imagery, in reality, the sad catastrophe that they reported devastated the home front while two armies tore each other part in the fields of western Maryland. The fighting in Maryland, in contrast to the disaster near Pittsburgh, would receive national media coverage in the weeks following the day’s end.

Earlier in 1862, prior to the explosions, the bustling United States Arsenal along the Allegheny River encompassed approximately 38 acres of land and employed a staff of approximately 1,200 people, which towered in comparison to the site’s pre-war work force. The arsenal’s laboratory was a multi-room complex, stirring with activity and the aroma of gunpowder hanging in the air. As laboratory employees busily worked with the explosive substance, it frequently spilled on the floor, and much of it was swept into the macadamized road outside. On September 17, 186 workers labored in the laboratory buildings - 156 of whom were young women - all toiling away and assembling small arms and field munitions for US troops on the front. It was payday at the arsenal, and tragically, for many of these workers, it would be their last.

Wagoner Joseph R. Frick had worked throughout the day, delivering cylinders, gunpowder, and ammunition to various sites around the compound, including the arsenal laboratories situated on a hill overlooking the Allegheny River. The clock neared 2:00pm as Frick turned down the macadamized road that led to the laboratory, where he would make his final delivery for the afternoon. After Frick unloaded several 100 lb. barrels of gunpowder, Robert Smith, a 19-year-old worker, called to Frick to have him remove some empty boxes from the laboratory porch. At that point Frick “saw on the ground, in the space between his wagon and the porch, some four feet, a flame of fire as from powder mixed with dirt; it made a fizzing noise.” By the time Frick noticed the spilled gun powder burning along the macadamized road, it was too late for him to act.

The ensuing blast from the combusted gunpowder at the laboratories threw Frick from his wagon into a nearby fence, but not before witnessing the death of young Smith. As it was later reported, “Smith was blown to pieces - part of him was found above the magazine, four hundred yards from the building.” Frick, although covered in debris, was among the first to witness the horrors of what would transpire over the next six minutes. Another witness, Rachel Dunlap, later testified that she “saw a blaze under the front wheel of the wagon” and shortly after, heard the explosion, at which point she was knocked down by an unseen object. With the aid of her sister, Dunlap escaped the laboratory with her life. Likewise, sisters Laura and Maria Guinn were exiting the laboratory as Maria showed Laura her month’s pay, when the explosion occurred. Laura later reported that she never saw her sister again. Laura was found running down a nearby street with her dress on fire. When others later inquired as to her memory of the event, she remembered “no more, and for months lingered between life and death.”

The Pittsburgh Daily Post reported the following day, “So great was the force of the explosion that fragments from the laboratories were thrown hundreds of feet. Shreds of clothing were found in tree tops… Of the main building nothing remained but a heap of smoking debris. The ground about was strewn with fragments of charred wood, torn clothing, balls, caps, grapeshot, exploded shells, shoes… Two hundred feet from the laboratory was picked up the body of one young girl, terribly mangled; another body was seen to fly in the air and separate into two parts; an arm was thrown over the wall; a foot was picked up near the gate; a piece of skull was found a hundred yards away, and pieces of intestines were scattered about the grounds. Some fled out of the ruins covered in flame, or blackened and lacerated with the effects of the explosion, and either fell and expired or lingered in agony until removed.”

In response to the quickly deteriorating situation, Assistant Ordnance Officer Lieutenant John R. Edie joined several witnesses in pulling a fire engine toward the burning laboratories. Starting at a nearby pond, Edie and others formed a line as they passed buckets of water toward the ensuing inferno. Several miles away in Pittsburgh, the dull boom of what sounded like cannon alerted residents and workers to what could have been misinterpreted as an attack by enemy troops. In minutes, firefighters from the city rushed to the site of the accident, yet were met with the same macabre scene that greeted witnesses and loved ones. The Pittsburgh Gazette described the aftermath, “The most appalling sight was the burning bodies. In some places they lay in heaps, and burnt as rapidly as pine wood, until the flames were extinguished by the firemen… The steel bands remaining from the hoop skirts of the unfortunate girls, marked the place where many of them perished… As soon as the fire was subdued, the removal of the bodies was commenced. But very few could be recognized, as heads, arms and legs were generally gone. The remains were conveyed on boards, and placed a different points on the grounds, to await further disposition… many were utterly consumed…”

In addition to the disastrous explosions and fire that consumed the arsenal laboratory, victims were also met with murderous small arms and artillery fire as munitions were ignited at the site. The next day, Colonel of Ordnance John Symington noted that, "the whole proceeds of the day…consequently exploded amounting to about 125,000 of .71 and .54 small arm cartridges, and 175 rounds of field ammunition assorted for 12-pounder and 10-pounder Parrott guns.” He continued, “The Civil Authorities of Pittsburgh and Lawrenceville have to day made preparation for the interment of the bodies.”

On September 18, 1862, the shocked and devastated Western Pennsylvania community of Lawrenceville buried the remains of approximately 40 friends and loved ones in a mass grave - a practice which aligned with that of traveling armies on the war front. Those whose remains could be identified were buried in plots scattered about Allegheny Cemetery and neighboring St. Mary’s Cemetery. Hours after the disaster, Allegheny Cemetery President Thomas Howe announced that a “suitable and appropriate lot in the Allegheny Cemetery” would be set aside for the “unfortunate victims of the heart-rending casualty which occurred this afternoon at the Allegheny Arsenal…as a testimony of the earnest sympathy of the managers of the cemetery…to the families of so many of our citizens.” The memorial that marks the final resting place of the unknown reads:

“Tread softly this is consecrated dust, forty-five pure patriotic victims lie here. A sacrifice to freedom and civil liberty, a horrid moment of a most wicked rebellion. Patriots! These are patriots graves, friends of humble, honest toil, these were your peers. Fervent affection kindled these hearts, honest industry employed these hands, widows and orphans tears have watered this ground. Female beauty and manhood’s vigor commingle here. Identified by man known by Him who is the resurrection and the life, to be made known and loved again, when the morning cometh.”

While an exact cause of the explosion was never determined, it is believed that a spark from Joseph Frick’s wagon wheel, or perhaps a horseshoe, may have ignited the gunpowder which ultimately claimed the lives of 78 workers at Allegheny Arsenal. Two investigations were launched in order to determine not only the source of the deadly blasts, but also those who may have been at fault. Colonel Symington and Lieutenant Edie, as well as Lieutenant Jasper Myers, Arsenal Superintendent Alexander McBride, and Assistant Superintendent James Thorp, were all considered guilty of gross neglect and failure to ensure the proper disposal of explosive materials. Although they were later exonerated, the three army officers were eventually re-assigned, while the superintendents remained in place for the remainder of the war.

Ten days after the burial of the unknown dead, Reverend Richard Lea of the Lawrenceville Presbyterian Church, an eyewitness to the violence of September 17, delivered a moving sermon to his congregation. Just as many families in the local community had been left with empty chairs in the home, the church pews there were vacant of three parishioners. Reverend Lea recalled the horrors of that day as if he were still there, hearing the cries of anguished victims and “conversing with so many dying persons in so short a space of time,” which left “a deep impression” on the elderly Lea. Many of the sights Lea encountered, however, were human remains that were “a short time before… life and beauty.” He pondered, in a foreboding tone, about the late devastation and its place within the larger national tragedy, “Who could foretell what the firing of the first gun at Fort Sumter would bring about? It brought about remotely, the catastrophe of Wednesday. And who can tell what more it may bring?”

Further Reading:

Pittsburgh During the American Civil War: 1861-1865, By: Arthur B. Fox.