The Treaty of Ghent: Ending the War of 1812

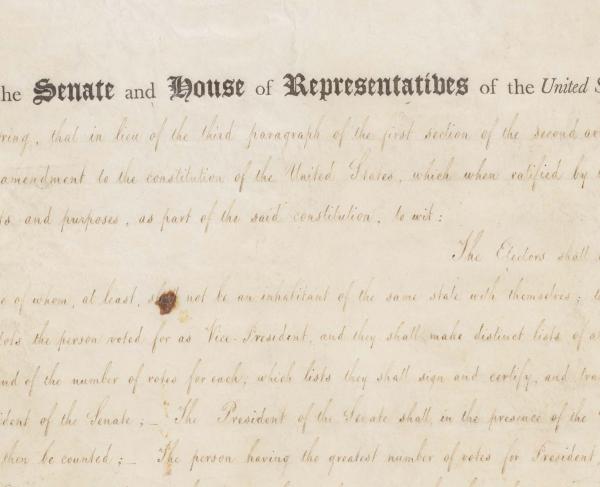

Painting of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, 1814. Sir Amédée Forestier, The Signing of the Treaty of Ghent, Christmas Eve, 1814, 1914, oil on canvas,

After two years of war between the United States and Great Britain, the Treaty of Ghent was signed on Christmas Eve, 1814, and its terms hurried across the Atlantic for ratification by the U.S. Congress. Poor weather delayed the ship carrying the treaty, and before it arrived, the Americans won a major victory at New Orleans. The treaty was quickly approved by Congress, and peace was officially established on February 17, 1815. British-American borders were restored to the status quo antebellum, and the futures of both Canada and the United States were secured.

By late 1814, both sides eagerly sought peace. The Napoleonic Wars were ending in Europe, freeing up British forces to commit to the American conflict. American politicians feared an escalation accordingly. At the same time, the threat of impressment into the British navy—which had been such a significant cause of the war— diminished. Finally, the American economy suffered severely from the lack of trade with Britain, especially in the New England States. New England Federalists who met at the Hartford Convention flirted with the idea of secession to end the war, reflecting widespread discontent. The governor of Massachusetts, Caleb Strong, even attempted to begin negotiations for a separate peace.

At the same time, the war was unpopular in Britain, whose economy and population were exhausted by over a decade of war. British forces failed to maintain control of the Great Lakes and lost the battle of Lake Champlain in September, making the prospect of actually holding American territory even more difficult. Other defeats like those at Baltimore and Fort McHenry similarly undermined British bargaining power. The Duke of Wellington himself, fresh from victory over Napoleon’s armies, recommended suing for peace. Meanwhile, the victorious nations met for intense negotiations at the Congress of Vienna, determining the reorganization of Europe—and some of Britain’s key allies, like Tsar Alexander I of Russia, were sympathetic to the American cause.

Five peace commissioners represented American interests at the negotiations: John Quincy Adams, Albert Gallatin, Henry Clay, Jonathan Russell, and James A. Bayard. Adams, Gallatin, and Bayard had been appointed in 1813, when the Russian government had offered to mediate peace talks, but their original efforts at peace failed when neither side would compromise on the issue of impressment. All five were skillful negotiators, and most had distinguished political careers—Adams as a future president of the United States, Clay as the “Great Compromiser” who secured the Missouri Compromise. Adams and Clay sometimes clashed over conflicting eastern and western interests, but both gave credit to Gallatin, a former Secretary of the Treasury, for settling internal debates and leading the commission.

Admiral James Gambier, Dr. William Adams, and Henry Goulburn represented British interests in the negotiations for peace, although they had somewhat less authority than the Americans did and often referred difficult questions back to London. Negotiations between the two teams began on August 8, 1814, in Ghent, Belgium. The United States had abandoned an end to impressment as a key war aim several months earlier, viewing it as an unrealistic goal after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. But the original British terms nevertheless appeared unacceptable to the American commissioners. The British pushed for full acknowledgment of British maritime rights, including impressment; a demilitarization of the Great Lakes; expanded Canadian borders, including territory in Maine and Minnesota; and the establishment of a protected region for Britain’s Native American allies in the Old Northwest, which would also serve as a buffer zone between the United States and Canada. This last demand was especially objected to by the American commissioners, as it would uproot thousands of settlers from their homes and threaten the United States’ westward expansion.

The following months of negotiations mostly consisted of a gradual reduction of British demands. The Americans had an advantage on the home front, where President Madison publicly shared news of the peace negotiations and recent victories like that at Baltimore boosted American morale. The British government, however, kept the details of the negotiations secret, and the prospect of increased taxes to pay for another North American campaign was deeply unpopular. The British soon offered uti possidetis as a condition for determining postwar boundaries—that is, each side would retain control of whatever territory they held at the end of the war. The Americans pushed instead for a return to the status quo antebellum borders, and eventually succeeded. A further commission was established by the treaty for determining disputed areas along the Canadian-American border, and another for determining disputed fishing rights. And the proposed Native American territory was reduced to a return of Native American territory and status circa 1811—a weak promise soon broken by continued American expansion. Both sides agreed to return prisoners-of-war and work together to end the international slave trade.

The treaty was signed on Christmas Eve and ratified by the British government on December 27th, but would not take effect until ratified by both sides. This condition had been a British proposal, designed to pressure the American government into quickly accepting the terms of the treaty. A ship bearing the treaty departed on January 2, 1815. While the ship was still in transit, General Andrew Jackson defeated British forces at the Battle of New Orleans, a significant victory for both commerce and American morale. But on February 13th, news of the treaty arrived in Washington, DC, and it was approved unanimously by the Senate on February 16th. Although specific American war aims like the end of impressment had not been won, the American celebrated the end of the war, and the ruling Democratic-Republican party flourished. American sovereignty was protected, and the United States had once more survived attempted conquests by the powerful British Empire, even if American victory remained ambiguous. The United States and Britain would not go to war again, and over time, became strong allies during conflicts in the 20th Century.