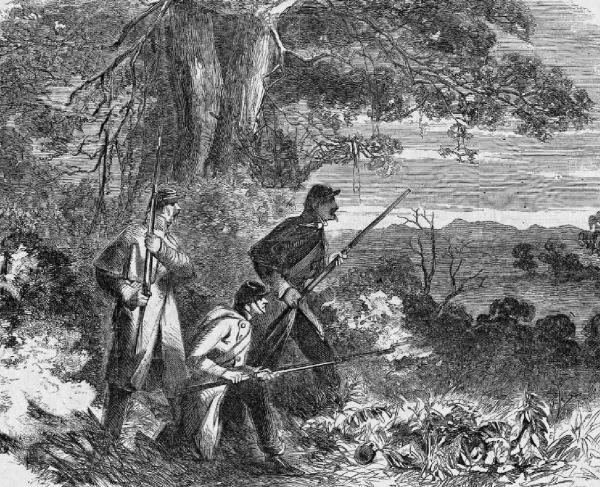

President Abraham Lincoln as he watches Our American Cousin at Ford's Theater in Washington, D.C., on 14 April 1865 — the moment before his assassination.

Theater has long thrived in the land we know as the United States, as the trials and tribulations presented in different works often have timeless relevance when juxtaposed with American events and society. While numerous playwrights’ products came to life on makeshift and professional stages across the American continent, the work of William Shakespeare was — and remains — especially prominent.

William Shakespeare: The Play’s The Thing!

In the time before radio, film, television and the internet, the theater inhabited a larger role in public entertainment than it does today. A 1919 study deemed The History of Theatre in America identifies 1752 as the year that professional thespians first took to the stage in the 13 colonies, with the arrival of a troupe from London. They were preceded by some two years by a more amateur production of Richard III in New York City.

Despite the passage of laws forbidding the performance of stage productions on moral grounds by several northeastern colonies in the 1750s, American theatrical traditions soon took hold in earnest. In 1767, Thomas Godfrey’s The Prince of Parthia became the first professionally produced play in Britain’s American colonies written by a native-born author. The previous year, Robert Rogers, a colorful figure of the French and Indian War, had published in London a stage play called Ponteach [Pontiac]: or the Savages of America, widely reputed as the first drama to tackle topics from a uniquely North American perspective — notably a sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans.

But no playwright was more widely read or produced for the stage than the “Bard of Avon,” William Shakespeare. During the Revolution, his plays lent the Patriots and the British a common popular language. In Corpus Christi, Texas, during the Mexican-American War, soldiers who would later make a name for themselves in the Civil War were cast in a U.S. Army production of Othello in 1846. While the six-foot James Longstreet was originally cast to play Desdemona in the production, it was decided that he was too tall to play the female character, opening the door for the 5′6″, 135-pound Ulysses S. Grant to take his place.

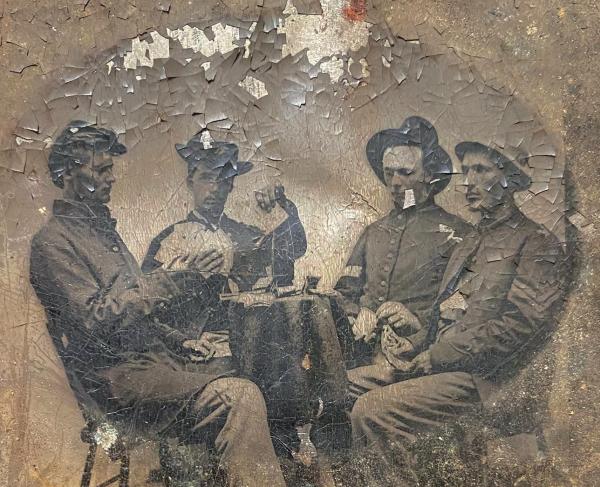

Soldiers in camps and actors on stages both North and South performed Shakespeare’s works during the Civil War. As Chicago newspaperman Elias Colbert said in 1864, “It is of the heart that Shakespeare speaks,” and his heart-drawn words were borrowed by not only soldiers and actors, but also cartoonists, writers and President Lincoln himself to emote the chaos of the world around them. And what’s more fascinating is how this era of American history was recorded like none other before, through new media like photography and chromolithography. Images of Shakespearian actors in costume and broadsides and posters brought Shakespeare’s words to audiences far and wide.

Shakespeare has inspired and confounded for hundreds of years, but his words found an added layer of complexity when mixed with the drear conflict of the Civil War. As many were familiar with his work, Shakespeare became a comfort in camp, a source through which one could better express love or tragedy, a reminder of reality versus fiction and a path that allowed a handful to live out — or act out — their dreams.

Before he took on the role of president, Abraham Lincoln would look to Shakespeare when he was a young lawyer traveling from town to town. He was even said to have kept a copy of Macbeth in his back pocket and quoted from it regularly. In an 1863 letter to actor James Hackett, Lincoln wrote, “Some of Shakespeare’s plays I have never read, while others I have gone over perhaps as frequently as any unprofessional reader. Among the latter are Lear, Richard Third, Henry Eighth, Hamlet, and especially Macbeth. I think nothing equals Macbeth — It is wonderful.”

That makes it especially ironic that Lincoln’s assassin, Shakespearean actor John Wilkes Booth, rose to fame in no small part for playing the Scottish king. In the wake of the assassination, people across the nation ached at the loss of the great leader and searched for ways to express their grief. Yet again, folks turned to Shakespeare to find words fit to describe the tragedy. On broadsides, a sketch of the shooting could be found coupled with a quote from Macbeth:

“Hath borne his faculties so meek; has been

So clear in his great office; that his virtues

Shall plead, trumped-tongued, against

The deep damnation of his taking off.”

(Act 1, Scene 7)

The lines come as the eponymous character is praising King Duncan for being a virtuous leader whose legacy will not be contained to his time on Earth — all the while plotting to murder said king! Americans looked to King Duncan’s assassination and drew a clear connection to the real atrocity before their eyes.

And it wasn’t only those mourning Lincoln who found comfort in Shakespeare. After assassinating the president, Booth was on the run for nearly two weeks. In an April 22, 1865, diary entry, he contemplates Julius Caesar, writing, “I am here in despair. And why; for doing what Brutus was honored for…” before closing with a line from (again) Macbeth: “but ‘I must fight the course.’ Tis all that’s left me.”

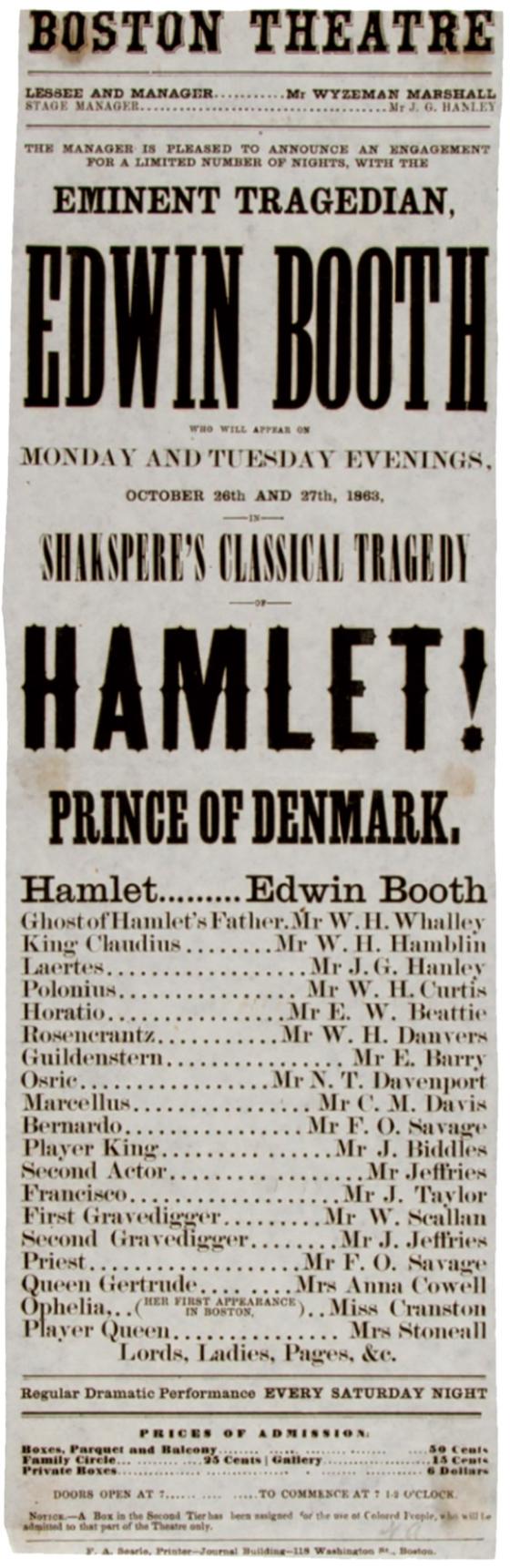

Although Booth is widely remembered today, in the 19th century, his brother Edwin enjoyed more stardom. The pair, along with brother Junius Brutus Jr., and father Junius Brutus, were all Shakespearean actors. Edwin played the title characters Macbeth and Hamlet, the latter being such an adored part that he played it in 100 shows at Broadway’s Winter Garden Theatre.

In 1864, upon Shakespeare’s 300th birthday, Edwin was part of a group of actors and theatre managers that successfully advocated for a statue of the Bard to be erected in New York’s Central Park. The cornerstone was placed between two elms in the park, but work would need to be done to raise the necessary funds to bring the statue to fruition. And so, later that year, the Booth brothers — in a rare event — joined together in a production of Julius Caesar to fundraise toward the statue, which was dedicated in 1872.

In addition to his work to advance social justice, Frederick Douglass was a philanthropic patron of the arts and used his many connections in Washington to grow the careers of Black artists. He was also a fan of William Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s works not only had a place in his library — they would furthermore make appearances in his speeches, and he would frequently attend performances of Shakespeare at local D.C. theaters. He even participated in the Uniontown Shakespeare Club’s readings at least twice. In a letter dated December 1877, Douglass wrote about participating in a reading with the club: “The play was the Merchant of Venice and my part Shylock.”

Beyond Shakespeare: The Theatrical Offerings of the Essayons Dramatic Club

While Shakespeare’s work was well-known to 19th-century audiences, it was hardly the only fare to which American theatergoers were treated during the Civil War. In fact, Shakespeare’s plays were often only part of a typical night at the theater in the mid-1800s.

This may seem odd to modern audiences accustomed to seeing a single performance, perhaps King Lear or Oklahoma!, and calling it a night. Nineteenth-century patrons, however, would have considered this a swindle — especially at today’s prices! No, the average night at the theater in the 1850s and 1860s typically consisted of two full-length plays, often a drama or tragedy, followed by a farce or some other sort of lighter fare designed to send audiences home happy. Various variety acts (singing, ballet numbers, acrobatics) filled out an evening that one actor of the period called a “motley mixture of amusements.” It was, therefore, quite common to see actors who had made a name for themselves as tragedians in Shakespeare’s works traipsing the boards in broad comic turns—sometimes on the same night. And all for 25 cents!

One popular comedy of the period was The Toodles, a “laughable farce.” according to one newspaper. Its principal characters were two men named Timothy Toodles, with the only distinction between the two being that one Timothy was “the less,” while the other was “the fat.” The role of Timothy the Less had been originated in the United States by well-known actor and playwright William E. Burton and was apparently a showpiece for popular comedians of the day. According to various accounts, the play’s most noteworthy moment was a “drunken scene” that provided “the actor who undertakes the part of Timothy Toodles [the Less]” his only “opportunity for the display of ability.”

Of course, farces like The Toodles did not always satisfy a more discerning crowd. Commenting on a recently transferred production, one London critic decried its “rambling, incoherent and wholly uninteresting plot of the melodramatic order” and concluded that the whole piece was “beneath contempt.” (Even then theater critics seemed incapable of having a good time.) Such criticism aside, The Toodles was performed in theaters throughout the United States before, during and after the Civil War, often as the final attraction of a typical theatrical experience.

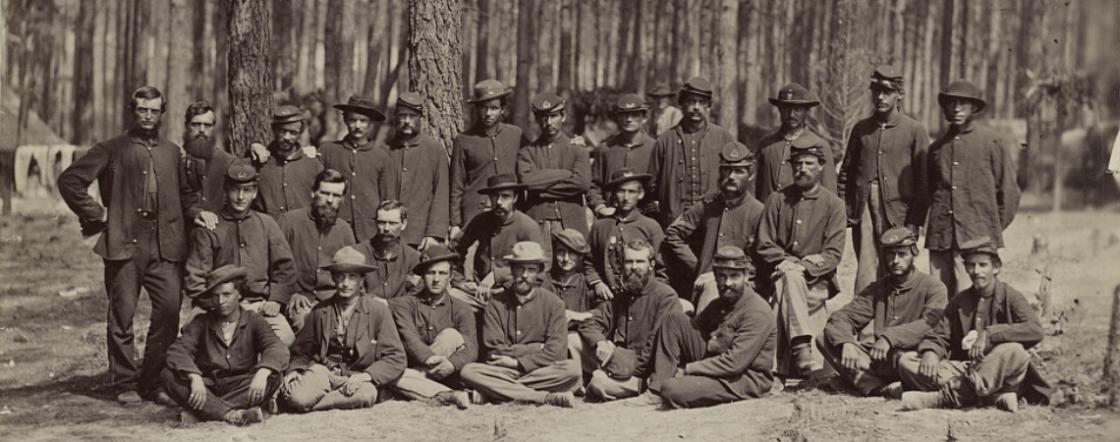

It is no surprise then, that The Toodles made its way into the 1864 winter camp of the Army of the Potomac at Brandy Station. It was there that the U.S. Engineer Battalion formed the Essayons Dramatic Club, one of many ad hoc theatrical troupes formed in both armies. Unlike those other clubs, the U.S. Engineers had the skill and wherewithal to build their own theatre — a structure sound enough that it was later used as a guard house.

The players were all enlisted men of the battalion and thus represented a cross-section of men from throughout the North. That such a group would form a dramatic club gives us some indication of just how widespread and popular theater was to Americans in the Civil War era. After forming on January 27, 1864, the men pieced together an orchestra and presented a performance of The Toodles a month later.

The presence of live music at the Engineers’ performance provides an idea of what a production of the Essayons Dramatic Club might have looked like in 1864. Very few, if any, members of the club were professional actors. We can therefore imagine that any performance would have showcased their individual gifts and talents, all with one singular goal in mind: to entertain an audience that would have expected variety as a key feature of a theatrical outing. Perhaps a few intrepid amateur tragedians tried their hand at a few speeches from King Lear or Hamlet. Musically gifted soldiers might have followed up with some popular songs of the period, perhaps with lyrics adapted to poke fun at army life. A popular comedy — in this case, The Toodles — might then have rounded out the event. This “motley mixture” might not pass for good theater in 2021, but it would have fit the bill for the Army of the Potomac in 1864. What’s more, it was the kind of theatrical performance 19th-century Americans expected.

While a majority of Civil War soldiers’ drama clubs are difficult to document, the Essayons Dramatic Club has an interesting and well-documented legacy. After closing shop at Brandy Station just before the Overland Campaign, the troupe seems to have been inactive for the remainder of the war. This is not surprising, as the engineers were quite busy with the siege operations outside Petersburg.

After the war, however, the Engineers revived the drama club at the Engineer School at Willets Point, New York. Now branded as the Willets Point Dramatic Club, the group produced plays until the end of the century. The Engineer School moved to the Washington, DC, area at the beginning of the 20th century, first to present-day Fort McNair in Arlington, Va., then again to Camp Humphreys — now known as Fort Belvoir.

The Essayons Dramatic Club officially reconstituted itself in 1923, and apart from a hiatus during World War II, continued to stage theatrical productions for nearly 45 years. During that time, the troupe’s productions included a variety of plays, some of them relatively obscure works, like A Taste of Honey, whereas others were 20th-century classics like George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s You Can’t Take It With You. Interestingly enough, the Essayons’ 1949 staging of the latter was produced by an engineer officer with his own unique lineage: Lt. Col. George E. Pickett, the grandson of the Confederate general.

When the troupe permanently disbanded in the 1960s, the Essayons Dramatic Club was one of the oldest amateur theatrical organizations in the United States.