In the aftermath of the firing on Fort Sumter, young men across the North flocked to the colors in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s calls for 75,000 volunteers. In fact, states filled their quotas so quickly that would-be soldiers had to be turned away. Civilians—women in particular—were just as enthusiastic to support the Union, organizing in sitting rooms, churches, and schools throughout the country. There was no shortage of work to be done and no shortage of hands to do it. However, it became clear that this surfeit of patriotism would soon exceed the government’s ability to direct it. How could all this enthusiasm be marshaled into a practical means of supporting the rapidly growing United States Army?

The United States Sanitary Commission was the answer to that question. It served as “the great artery bearing the people’s love to the people’s army.” It had its origins with the Woman’s Central Association of Relief, an informal gathering of approximately 50 women, who met in New York City on April 25, 1861—a mere ten days after Lincoln’s call for volunteers. Their initial aim was to “organize the whole benevolence of the women of the country into a general and central association.” These women sought the advice of Rev. Dr. Henry Whitney Bellows, the pastor of New York’s First Congregational (Unitarian) Church. “You must find out first what the Government will do, and can do,” instructed Bellows, “and then help it by working with it and doing what it cannot.” Physicians and surgeons from New York City medical associations quickly joined the fold, forming the nucleus of a philanthropic agency that eventually spanned the whole of the north.

Bellows and his associates wrote to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, offering their services. They looked to create a commission composed of “medical men, and of military officers…who shall be charged with the duty of investigating the best means of methodizing and reducing to practical service the already active but undirected benevolence of the people toward the Army.” At the same time, they wrote to acting surgeon general of the United States, R.C. Wood, who, in turn, expressed his support for the commission. Citing “very great and urgent” pressure on the Medical Bureau, Wood complained that “much remains to be accomplished by directing the intelligent mind of the country to practical results connected with the comforts of the soldier, by preventative and sanitary means”—the very help Bellows and his comrades had offered the government. “The Medical Bureau would,” in Wood’s judgment, “derive important and useful aid from the counsels and well-directed efforts of an intelligent and scientific commission” such as the one proposed by Bellows. “The selection of this Board,” he added, “is of the greatest importance.”

This effort was not without precedent. During the Crimean War, the British public had been alarmed at the high mortality rates among their sick and wounded soldiers. The British Sanitary Commission formed to alleviate this issue, but only towards the end of the war. “The civilization and humanity of the age, and of the American people,” argued Bellows, “demand that such a commission should precede” a conflict on American soil. “We wish to prevent the evils that Engaged and France could only investigate and deplore.”

In America, Secretary of War Cameron approved the establishment of the Commission on June 9, 1861, with President Lincoln giving his endorsement later that week. Though he supported the commission, the president “feared it might be the fifth wheel of the coach.” Despite these misgivings, the United States Sanitary Commission was officially established on June 18, 1861, and given office space in the Treasury Building, next door to the White House. Reverend Bellows served as the Commission’s president with Frederick Law Olmstead—the landscape architect responsible for New York City’s Central Park—serving as executive secretary. Noted lawyer and diarist George Templeton Strong came on as the organization’s treasurer.

The Commission’s work fell into three broad categories, beginning with “materiél,” or more plainly, the soldiers themselves and the camps in which they resided. Volunteer soldiers underwent medical examinations to ensure they were physically fit enough to endure the rigors of active campaigning. Commission members also thoroughly inspected their camps. Such an inspection revealed disturbing realities of soldier life. In Washington, Olmstead reported that camps lacked proper drainage, tents were too crowded, and lavatory facilities were “unnecessarily and disgustingly offensive.” Inspectors found that a lack of discipline among the volunteers only made matters worse. Volunteers officers were generally found to be “generous and self-devoted” but “they rashly assume that intelligent men know how to take care of themselves; and they are already finding camp dysentery seizing their camps.” The Commission feared the state of the volunteer camps and the men in them “betokened the early demoralization, in not actual mutiny of the army.”

To remedy these ills, the Commission published a series of essays “on the best means for preserving health in camp, and on the treatment of the sick and wounded in camp and on the battlefield.” This dovetailed nicely with the Commission’s second key role: prevention. These treatises covered a variety of topics including amputations, “rules for preserving the Health of the Soldier,” and treatments for malaria, pneumonia, yellow fever, dysentery, and other common ailments. Regimental surgeons—the majority of whom had been small-town doctors before the war—received these reports with gratitude. These men had little experience treating gunshot wounds, let alone handling a mass-casualty incident like a battle. Nor had they the experience of managing hundreds of patients at one time. In fact, the Sanitary Commissions essays were so popular that additional copies needed to be printed. One early historian remarked there was “scarcely a surgeon in the Army who has not sent to the Commission for fresh copies.” The Commission also examined the soldiers “Diet, Cooking, Clothing, Tents,” and more. Thus, “[e]verything appertaining to outfit, cleanliness, precautions against damp, cold, heat, malaria, infection; crude, unvaried, or ill-cooked food, and an irregular or careless regimental commissariat” became the purview of the Sanitary Commission.

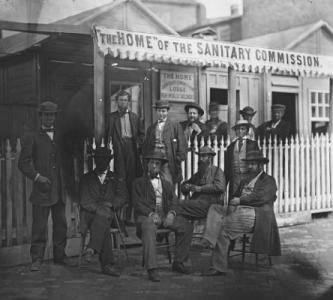

However, the Sanitary Commission is probably best known for its many relief efforts. In August 1861, troops arriving in Washington, found themselves thrust into a confusing situation in which the men were often separated from the baggage and medical equipment. The Commission stepped into the gap and provided “medicines, food, and care” that might otherwise have been neglected for weeks. The Commission also established a system by which regimental commanders and physicians could appeal directly to the Commission for supplies—thus avoiding the complications of government red tape. During the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, the Commission requisitioned large steam boats from the War Department and converted them into Hospital Transports. Ultimately, as many as 1,000 men could be cared for and transported by these vessels. “Relief” also included providing the army with essential food stuffs. In the 1863 Vicksburg Campaign, one inspector noted how veterans of Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg campaign “rallied from the depressing influence of wounds and amputations,” which he believed stemmed “largely” from “the avalanche of vegetables” provided by the Sanitary Commission. And, of course, Commission members were on the battlefield after nearly every major engagement of the war, providing care and comfort to survivors of Antietam, Gettysburg, Chattanooga and other battles. These efforts were not confined to the battlefield or the hospital. The Commission established and maintained several “Soldiers Homes,” hostels for convalescent soldiers, many of which remained in service long after the war.

The role of women in supporting the Sanitary Commission’s work cannot be overlooked. Female volunteers collected donations, sewed uniforms, and ran kitchens in army camps. Significantly, as many as 15,000 women volunteered in army hospitals, among them Dorothea Dix, Louisa May Alcott, and Eliza Emily Porter. These women and thousands of others provided essential assistance during surgeries, administered medicines and food to convalescent patients and changed dressings to wounds. They also provided much needed mental comfort to soldiers in their care, reading letters to them or taking dictation from soldiers looking to write home. Importantly, these women working with the Commission received wages for their efforts.

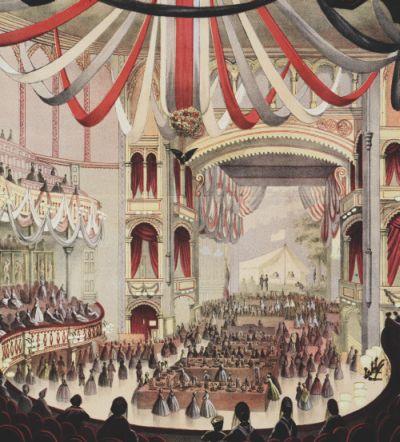

Women also played a significant role in the organization so-called Sanitary Fairs. These were massive fundraising events involving large-scale exhibitions, art installations, and parades. The first of these fairs, held in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1863 raised $100,000 (roughly $2 million in 2024). Similar events were held in Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York City, the latter of which (dubbed the Metropolitan Fair) raised more than $1 million for the cause. These funds allowed the Commission greater freedom to purchase the goods and supplies sent to the front.

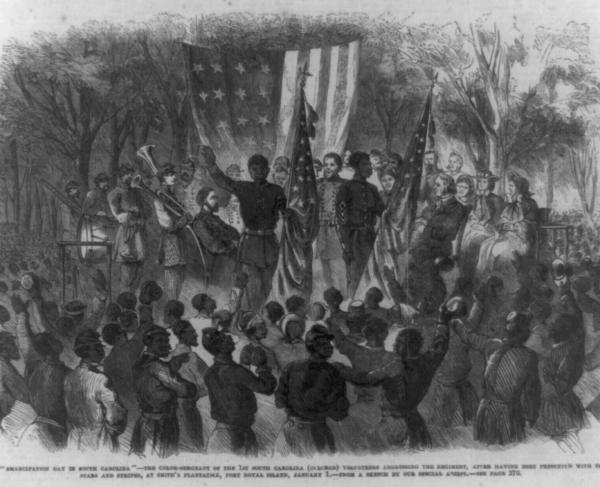

“The true strength and glory of a free people lies not it its politicians, orators, poets, and historians,” wrote one one member Commission, “but in the faithful instinct, courage an intelligence of the unnamed and unnamable millions.” The unnamable millions of Americans who supported the Sanitary Commission, either with their physical labor or financial support showed that strength. From its inception to the close of the war, the United States Sanitary Commission raised more than $25 million and provided essential support to the United States Army. Far from being the “fifth wheel" imagined by President Lincoln, it proved an invaluable ally to the federal government at a time when it was most needed. While it is impossible to measure how the army would have faired without its support, it is safe to say that the efforts it took to ensure the welfare of the of soldiers—on the battlefield, in camp, in hospital, and beyond—played a significant role in ensuring the war for Union and Emancipation was carried out to a successful conclusion.

Further Reading:

- Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women's Politics in Transition by Judith Ann Giesberg (2000).

- History of the United States Sanitary Commission: Being the General Report of Its Work During the War of the Rebellion by United States Sanitary Commission and Charles Janeway Stillé (1866).

- “The” Sanitary Commission of the United States Army: a Succinct Narrative of Its Works and Purposes (1864)

- The United States Sanitary Commission: A Sketch of Its Purposes and Its Work: Compiled from Documents and Private Papers by Katharine Prescott Wormeley (1863)