Coffee played a large role in the lives of soldiers on both sides of the Civil War, but the lack of coffee on the Confederate home front played a role in Southern morale. The blockade stopped coffee and other much needed supplies from filtering into most cities and rural areas throughout the South, and instead of going without coffee, citizens experimented with roasting vegetables and nuts to create a coffee-like drink, attempting to maintain some semblance of normality in their daily lives. In some instances, coffee made it through the Union blockade, but privateers and shopkeepers sold it at exorbitant rates. The price of coffee in the Confederacy rose from an average of $1.20 a pound in March of 1861 up to an average of $196 per pound in February of 1865. In one Confederate state, the cost of coffee per pound rose to $250, which a Union soldier had noted in his journal after reading a Confederate newspaper. In Savannah, a Confederate soldier on furlough thought he found a deal when he purchased two pounds of coffee for $30, but found out later on the road that it was not coffee at all, but peas.

Family group outside of their home, Cedar Mountain, Virginia, August 1862, by Timothy O’Sullivan. Collection of the Library of Congress

The inaccessibility of real coffee, whether because of cost or lack of distribution, contributed to a wide variety of coffee-like alternatives, both to create new beverages and to make what coffee was available last longer. In New Orleans, residents added ground and roasted chicory root to the coffee supply, since chicory tastes similar to coffee, and could be ground and sold at a low rate. This recipe is still used in New Orleans today and has become more of a traditional drink instead of one made out of necessity. In Arkansas, one woman made her coffee last by adding a spoonful of toasted cornmeal to a spoonful of coffee. She wrote: “I have used it for two weeks, and several friends visiting my house say they could not discover anything peculiar in the taste of my coffee but pronounced it very good. Try it and see if we cannot get along comfortably, even while our ports are blockaded...” A housekeeper in Charleston countered with a different recipe to stretch coffee “as these are times in which all are called upon to practice economy.” She wrote, “I was induced to try a mixture of two-thirds cottonseed and one-third coffee, and found it answered extremely well…We have been using it for six or seven weeks constantly in our family, and many of our friends who drank it without knowing what the mixture was, pronounced it equal to the best coffee.”

More often though, Confederate citizens resorted to experimenting with what they had to simulate the taste and consistency of coffee, as one Raleigh, North Carolina, woman stated, “necessity is the mother of invention.” These concoctions were coined ‘Lincoln coffee,’ and were often outlandish in both ingredients and preparation. One British officer, who was visiting the Confederate states in 1863, remarked “The loss of coffee afflicts the Confederates even more than the loss of spirits; and they exercise their ingenuity in devising substitutes, which are not generally very successful.” Several women confirmed this sentiment in their diaries and letters to friends and family. In her reminiscences in 1937, South Carolinian Ida Baker commented on some of the recipes she tried for both tea and coffee during the Civil War: "Everybody had to use parched wheat, parched okra seed, or parched raw sweet potato chips for coffee. Not even tea came in. We used sassafras and other native herb teas both daily and at parties when the herb teas were in season. Some were good, but the substitute coffee was not.” Julia Fischer of Georgia wrote that her family resumed drinking tea after becoming “so disgusted with the black muddy corn juice that is called coffee."

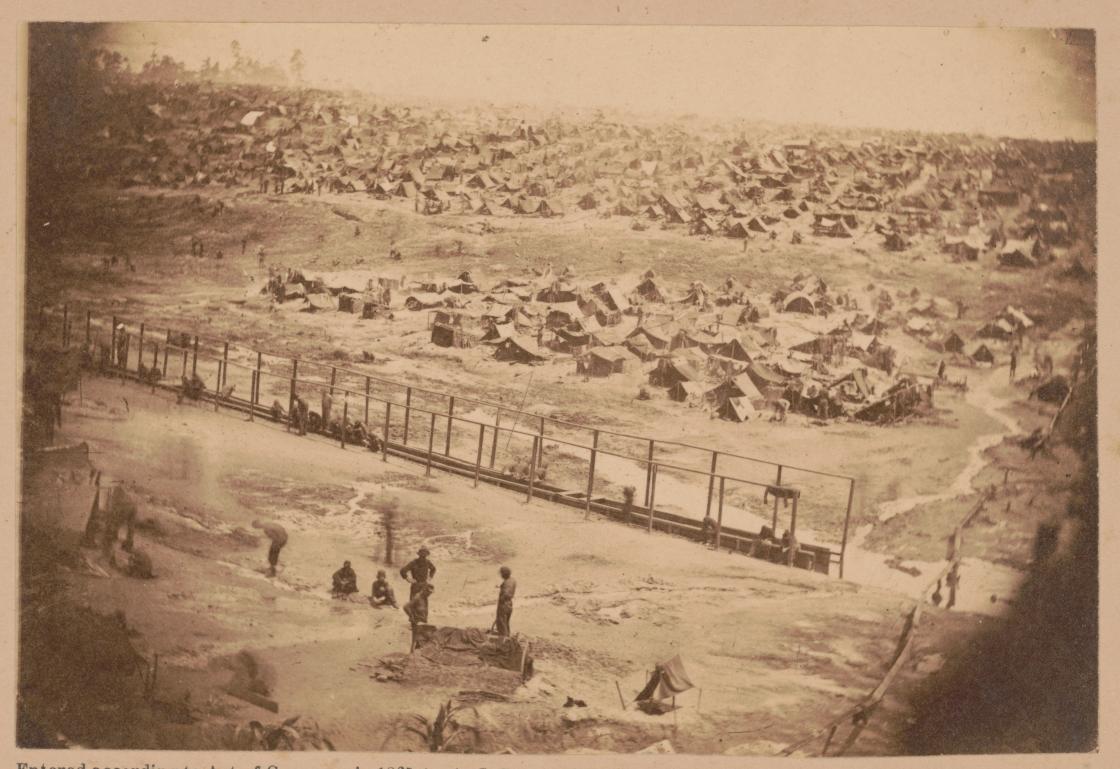

Prisoners at Andersonville Prison, Georgia, collecting roots for coffee by A. J. Riddle, 1864. Collection of the Library of Congress

Others felt differently about their creations. In Botetourt, Virginia, Julia Breckinridge wrote to her husband about the family’s foray into rye coffee. She offered to send him the recipe, and declared “I truly never care to drink any other drink….I believe that few persons could tell it from genuine coffee.” In a Tennessee newspaper, a reader stated, “We have been somewhat skeptical about the various substitutes that have been proposed for coffee….But, ‘the proof of the pudding is in the eating.’ We have tried the okra coffee, and had we not known it to be okra, we should have supposed it the best of Laguyra or Java.” In Georgia, sweet potatoes were declared the best: “Many worthless substitutes for coffee have been named. The acorn need only be tried once to be discarded. Corn meal and grits can be easily detected by the taste. Rye is only tolerable. Oakra [sic] seed is excellent, but costs about a dollar a pound, which puts it entirely out of the question. What, then, can we use? We want something that tastes like coffee, smells like it, and looks like it. We have just the thing in the sweet potato. When properly prepared, I defy any one to detect the difference between it and a cup of pure Rio.” Other ingredients for ‘Lincoln coffee’ included beets, acorns, field peas, peanuts, sassafras pits, parched wheat, carrot, sugar cane seeds, boiled down and burnt molasses, potato peel, persimmon seeds, and asparagus seeds.

Harvesting Wheat, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1860. Collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Some Confederate newspapers included bizarre recipes to take the place of real coffee. One such recipe from Macon, Georgia, declared that in roasting persimmon seeds mixed “with parched ground peas and now and then a cockroach thrown in, “it successfully imitated genuine coffee, and the submitter would “defy any man to detect the difference.” From the Arkansas True Democrat, a reader provided a recipe for gullible Union soldiers reading Confederate newspapers: “Take tan bark, three parts; three old cigar stumps and a quart of water, mix well, and boil fifteen minutes in a dirty coffee pot, and the best judges cannot tell it from the finest Mocha.”

Regardless of how one made his or her coffee, the options for substituting were limitless. In some cases, the health benefits of the substitutes were highlighted in order to justify the abhorrent taste. Once the war ended though, many Confederate citizens were relieved when the price of coffee returned to normal, and the necessity for substitutions came to an end. Whether on the battlefield or at home, coffee remained a motivator, a morale booster, and certainly a conversation starter!