Coffee has had a long and prosperous history with widespread origins, but its consumption during the Civil War, and alternatively, the unique substitutes for the lack of coffee in the Confederacy, were brought to astounding heights. In the United States, coffee wasn’t widely accepted until the American Revolution, when Great Britain implemented taxes and tariffs on imported tea. These tariffs infuriated American colonists, ultimately triggering the Boston Tea Party in December of 1773. As a result, patriots were persuaded to enjoy coffee instead, as tea remained unpatriotic. In a letter to his wife, John Adams declared that he wished for honestly smuggled tea, but when refused and offered coffee instead at an inn in Falmouth, Massachusetts, he stated: “I have drank Coffee every Afternoon since, and have borne it very well. Tea must be universally renounced. I must be weaned, and the sooner, the better.” Other patriots followed suit, and as unpalatable as coffee may have once seemed, it became the preferred drink after the Revolution.

In October of 1832, a change in army rations added to the climbing rate of coffee importation: President Andrew Jackson substituted coffee and sugar for a soldier’s daily rations of rum and brandy, citing complaints from military officers of insubordination and accidental injuries from overindulgence. With this modification, the importation of coffee into the US rose from 12 million pounds per year to over 38 million pounds. Coffee became the alternative to alcohol consumption, helping soldiers refuel, stay focused, and push through difficult situations. At the same time, the change in military rations further popularized coffee with the American public, and by 1840, New Orleans had become the second largest importer of coffee in the United States, thanks to its relative location to Brazil. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the United States imported over 182 million pounds of coffee, with New Orleans distributing beans both throughout the Southern states and in to New England.

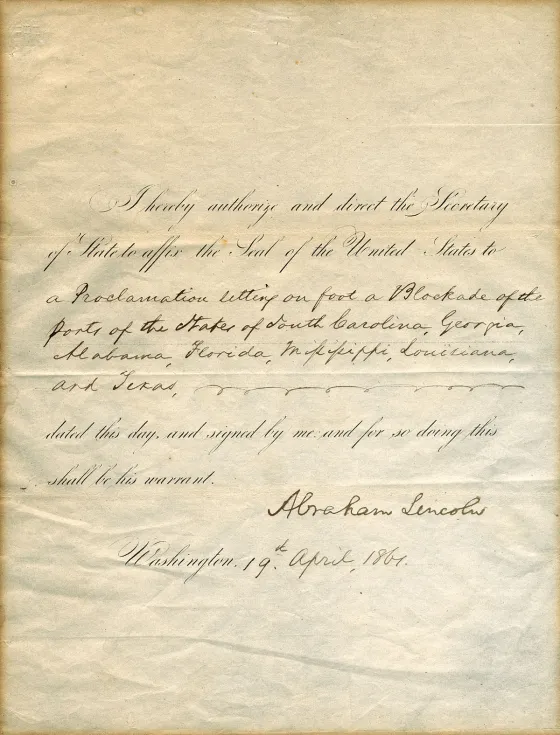

This large-scale importation of coffee into New Orleans changed as Southern states seceded from the Union in April of 1861. In an attempt to prevent war and bring the rebellious states back into the Union quickly, President Abraham Lincoln declared a blockade to all Confederate states one week after secession. The proclamation prevented the trade or purchase of goods, supplies, and weapons into or out of twelve ports throughout the Confederacy. Additionally, any ships, along with any items contained within the vessels, found conducting business with any of the eleven insurgent states would be forfeited to the United States government.

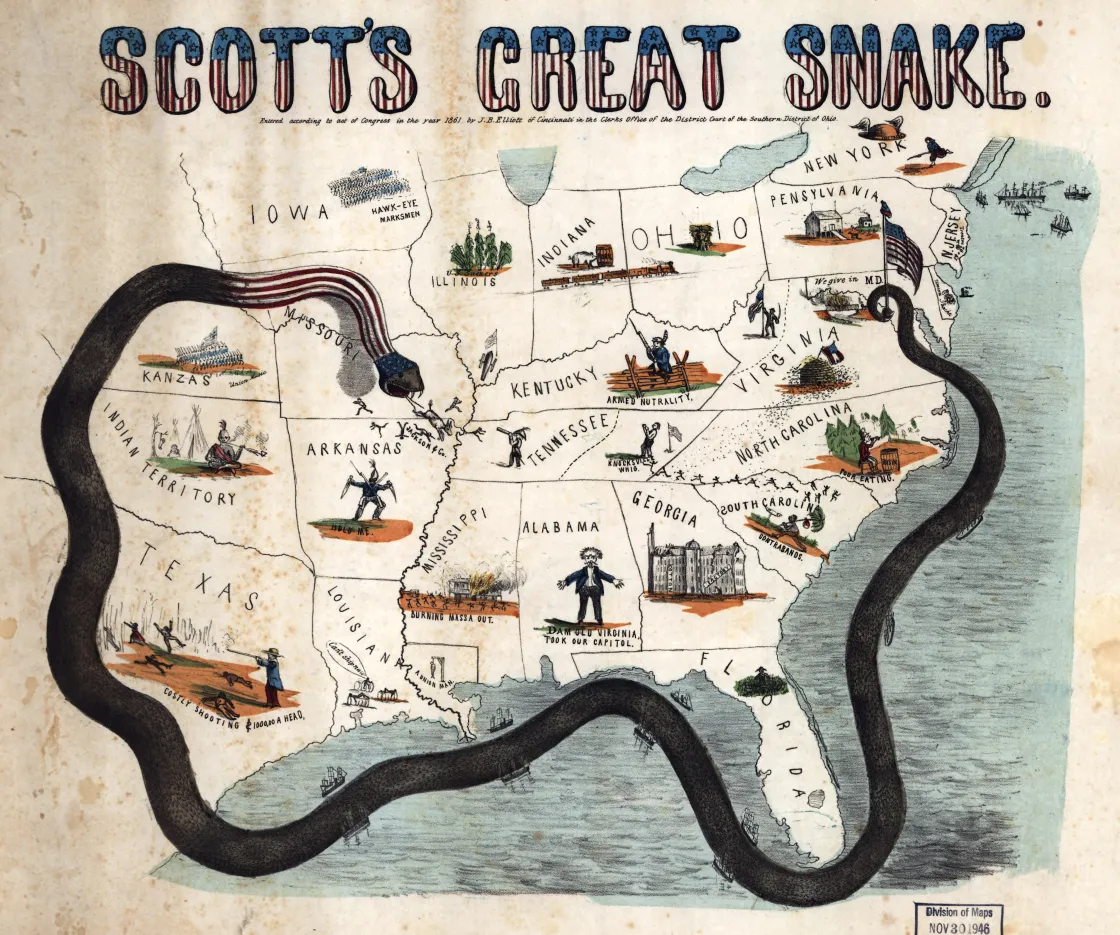

Union general Winfield Scott further expanded on Lincoln’s proclamation of blockading the ports by proposing the Anaconda Plan, not only cutting off trade into the southern ports, but aiming to stop any trade up or down the Mississippi River. Prior to the war, ferrying items up and down the river from New Orleans remained one of the quickest ways to transport and distribute goods into the Southern states. In creating this blockade down the Mississippi River, General Scott’s hope was to not only cut off trade, separating the states from each other but to avoid all-out war and bloodshed as much as possible. The importation and easy movement of coffee, along with sugar, iron, steel, and molasses, came to a halt.

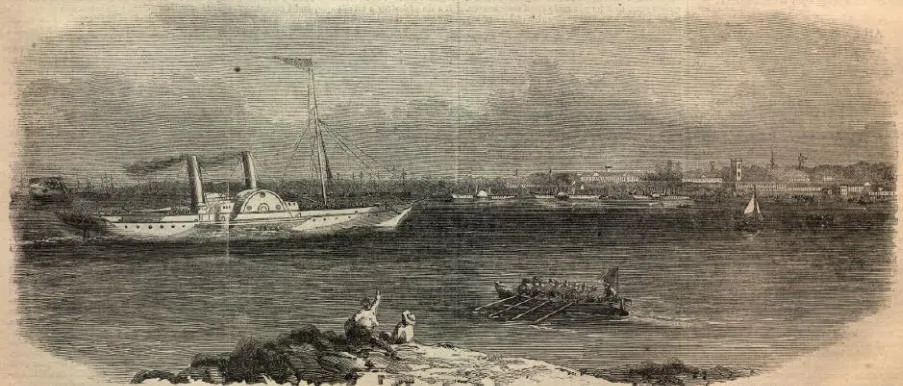

This double blockade of over 4,000 miles of Southern coast and riverfront up the Mississippi did not have the intended effect General Scott had hoped of ending the war before it officially started, but did apply pressure for the Confederate states to alter their course of action. By negotiating with European contractors and privateers, the Confederacy was able to successfully outrun the Union Navy for a period of time: the large expanse of territory was near impossible for the Union to efficiently patrol, and focusing their efforts on the largest port cities was problematic. In August of 1861, Union Navy officer Lewis H. West complained while on duty in Alexandria that Confederate privateers “could come and go as they please,” successfully navigating the Union blockade and depositing goods to much needed troops. One year later, Lewis hadn’t changed his mind: while serving in Charleston, South Carolina, he wrote in a letter to home: “The blockade is much the same as it always was. There has not been a night for the last two weeks that steamers have not run in and out, not one of which have been captured; and so it will probably go to the end.”

If privateers made it through the blockade, transporting and distributing goods throughout the Southern countryside without being caught became the next task. In 1863, one soldier marching through Shelby, Tennessee, commented, ‘General Wheeler captured and burned three [Confederate] transports on the Cumberland laden with provisions. One of them was loaded with coffee entirely. They cannot depend on getting supplies in this part of the country, for we have nearly consumed nearly all that can be found.’ Despite the Union’s limitations, the blockade had its intended effect as the war progressed, with fewer and fewer supplies making it through to the Confederate troops. As a result, coffee, a staple for many in the South prior to the war, became a luxury for both the troops and for those still on the home front.