As Confederate troops emerged from the woods along Seminary Ridge on July 3, 1863, they faced an intimidating sight: thousands of Union infantrymen and 75 cannons on Cemetery Ridge staring back at them. One Confederate captain recalled the daunting situation as company commanders “were instructed to inform their men of the magnitude of the task assigned to them.” That task – the destruction of the Union Army of the Potomac – had been General Robert E. Lee's elusive goal more than one year. Could these troops finally deliver a truly decisive Confederate victory... and on northern soil?

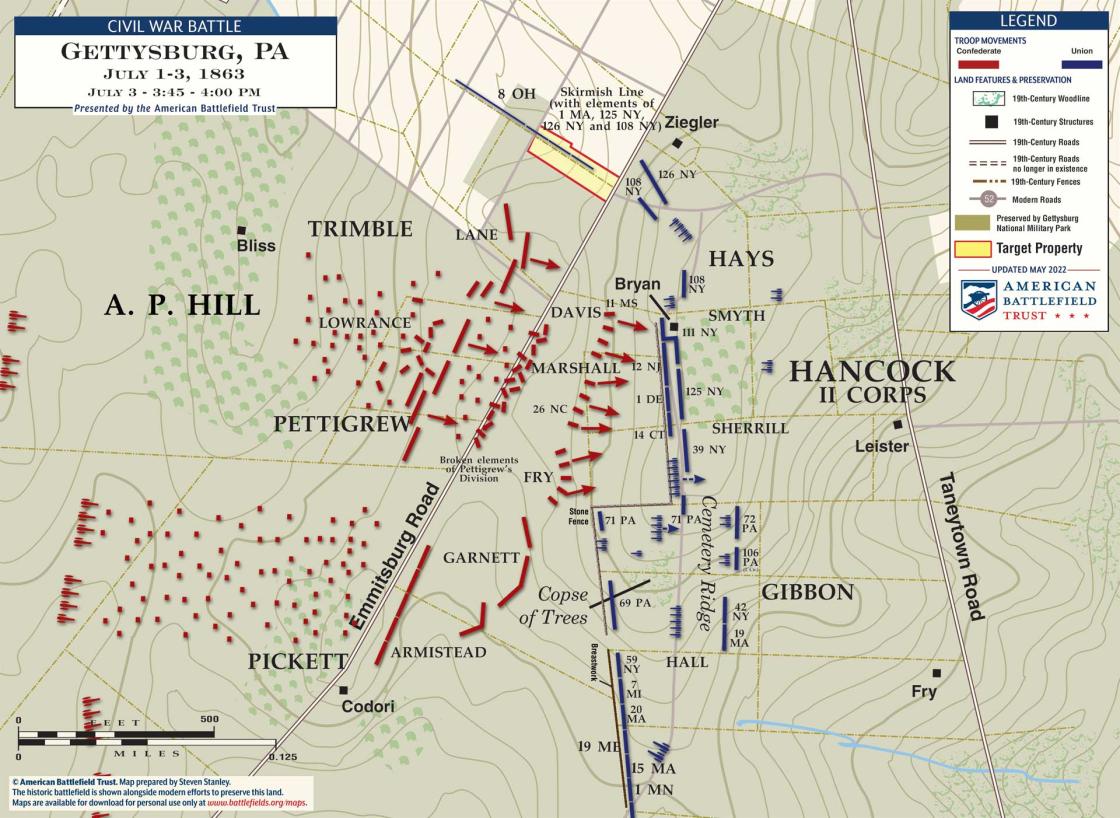

Although commonly known as Pickett’s Charge in the post-war years, this assault on the Union center at Gettysburg comprised two more divisions in addition to Major General George Pickett’s. After General Lee settled on the Union position along Cemetery Ridge as the assault’s objective, he decided to reinforce Pickett’s division with Major General Henry Heth’s division and two brigades from Major General William Dorsey Pender’s division. Because both Heth and Pender were wounded in the fighting on July 1 and 2, however, their divisions fell under the command of Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew and Major General Isaac R. Trimble.

When Pettigrew’s and Trimble’s men descended Seminary Ridge at approximately 3:00 that afternoon, they confronted the challenge of protecting their left flank. Lieutenant General James Longstreet, to whom Lee granted discretion to plan and execute the assault, expressed particular concern about this problem. As Pettigrew’s division stepped off first followed by Trimble’s, the task of protecting the column’s left flank fell to the brigades of Colonel John M. Brockenbrough and Brigadier General James Lane. Most accounts testify that the advancing column did not receive artillery fire until about halfway to the Union line, but as the Confederates neared this point, Federal artillery from Cemetery Hill and northern Cemetery Ridge opened fire. Major Thomas Osborn, commanding the Union Eleventh Corps artillery, wrote that “the whole force of our artillery was brought to bear upon this column, and the havoc produced upon their ranks was truly inspiring.”

Nevertheless, the Confederate infantry pressed forward through the shot and shell. Before long, Brockenbrough’s Virginians began to falter. Reduced by Union artillery to what one observer thought to be no more than a skirmish line, many of the Virginians likely did not advance far past the halfway point. Instead, Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis’s Mississippi brigade advanced as Pettigrew’s left flank. Standing near the present-day locale of “General Pickett’s Buffet” restaurant on July 3, an observer would have encountered a cathedral-like view of Pettigrew’s and Trimble’s soldiers. One could see Davis’s brigade surge forward through the smoldering ashes of the William Bliss farm toward the Emmitsburg Road only to face the waiting Union infantrymen at the Bryan farm atop Cemetery Ridge.

However, Longstreet’s fear became a reality as Davis’s Mississippians received from a Union skirmish line a withering fire through its left flank. Anyone standing at the site of Pickett’s Buffet would have been caught in the crossfire of elements of the 8th Ohio, 108th and 126th New York, and a company of Massachusetts Sharpshooters. While the Yankees poured lead into Pettigrew’s and Trimble’s flank, some Confederates returned fire. The concentrated effort of the Union soldiers so surprised the remaining Virginians of Brockenbrough’s brigade that they bolted toward the rear. With the Virginians either paralyzed or routed, the men of Davis’s and Lane’s brigade lacked adequate support. The Mississippians of Davis’s brigade, in addition to taking fire on their exposed flank, continued to be shelled by the Federal guns of Lt. George Woodruff’s battery, located just north of the Bryan farm in Ziegler’s Grove.

In the face of these odds, the Confederate column continued to push toward Cemetery Ridge. As Pettigrew’s men neared the Emmitsburg Road, they entered Union musket range. Davis’s boys hurdled the rail fence along the road while Yankee riflemen rose to greet them. Rounds of canister whizzed through the attackers, cutting them down by the hundreds. Nevertheless, some of the Mississippians succeeded in reaching the Bryan barn (and some fewer could almost touch the stone wall that marked the Union line), though most were killed, wounded, or forced to surrender. General Davis somehow escaped the carnage unscathed and later reported that there “was nothing left but to retire to the position originally held, which was done in more or less confusion.”

By the time Isaac Trimble and his two brigades reached the Emmitsburg Road, Pettigrew’s men were already falling back although a few of his men got within striking distance of the sone wall. Witnessing this scene, Trimble later wrote, “it would be a useless sacrifice of life to continue the contest.” During the fray, General Trimble received a leg wound which would necessitate amputation. Having suffered a wound in the same leg almost a year prior at the Battle of Second Manassas and spending much of the Gettysburg Campaign lobbying for an opportunity to fight, Trimble begrudgingly gave up on the onslaught. He ordered his brigades to reform behind the Confederate artillery and managed to make it back to Seminary Ridge himself.

Although General Lane tried to press his North Carolina brigade forward in a vain attempt to support Pettigrew’s left, he too fell victim to the withering flanking fire from the men of Ohio, New York, and Massachusetts. By this time the brigade to his left was crumbling, and Lane decided withdrew his men to the safety of the Confederate artillery. Watching from the line of the 8th Ohio, near the present-day restaurant, Lieutenant Colonel Franklin Sawyer recalled that as the Confederates reached the Union line, they “were at once enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke and dust,” while “a moan went up from the field, distinctly to be heard amid the storm of battle.”

When the smoke finally cleared, the outcome left no room for dispute. Pettigrew’s division lost an estimated 2,000 men as casualties as well as six battle flags. Trimble’s division lost some 1,035 men and five flags. From this same property near the Emmitsburg Road, Union soldiers of the flanking skirmish line might have been able to spot the imposing figure of Union General Alexander Hays dragging one of the captured flags in the dust as he galloped along the Union line.

Despite constituting roughly two-thirds of the assault, Pettigrew and Trimble’s divisions have received little attention compared to Pickett’s Virginians. While historians continue to debate the reason, the lack of early preservation efforts and the expansion of the town across this part of the battlefield could be partially to blame. But now, visitors to Gettysburg will have the opportunity to better interpret this forgotten flank of Pickett’s Charge like never before and understand the actions and sacrifices of Pettigrew and Trimble’s men as they ascended the storied slope of Cemetery Ridge.

Further Reading:

- Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg: A Guide to the Most Famous Attack in American History By: James A. Hessler and Wayne Motts

- Pickett's Charge in History and Memory By: Carol Reardon

Related Battles

23,049

28,063