The Battle of New Market is one of the most-written about minor engagements of the entire Civil War. This fascination is in large part due to the participation of the Corps of Cadets from the Virginia Military Institute. Yet for all the literature that has been written about New Market — much of it centering on the cadets — some aspects of the battle have not been fully appreciated, and other aspects of the battle that have been viewed as “fact” for decades may not be so. Valley Thunder: The Battle of New Market and the Opening of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, May 1864 is the first book-length assessment of the battle to appear in nearly four decades.

New Market was the opening phase of the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. A small Federal army of about 10,000 troops under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel was ordered to move south from Martinsburg, in what is now West Virginia, up (the Shenandoah River flows from south to north, thus, one moving south is going “up” the Valley) the Shenandoah Valley to Staunton, Virginia, a vital rail link between the Confederate capital of Richmond and the Valley. At Staunton Sigel was expected to meet up with another Federal column coming from the southwestern part of Virginia, and together to move against either Lynchburg or Charlottesville. Sigel’s assignment was in large part a diversionary one designed to attract Confederate attention away from the main Union army in Virginia, the Army of the Potomac, and also to deprive the Confederacy of the supplies coming from the Shenandoah Valley.

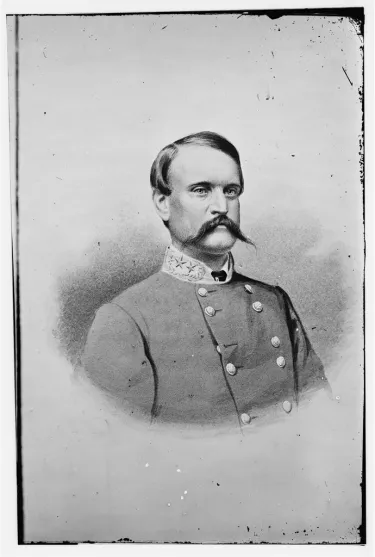

Sigel was opposed by an even smaller Confederate force of about 4,500 men under Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, which included about 250 young cadets from the Virginia Military Institute.

The two armies met on a rainy Sunday, May 15, at New Market, a small crossroads town in the central Shenandoah Valley. In a day-long battle, Breckinridge’s Confederates defeated Sigel’s forces, largely due to mismanagement by the Federal commander. During the battle’s climatic stage, the VMI cadets earned themselves a place in history by capturing a Federal cannon in the final charge. Sigel retreated to the vicinity of Winchester and was replaced several days later, and operations in the Valley would escalate shortly after Sigel’s removal.

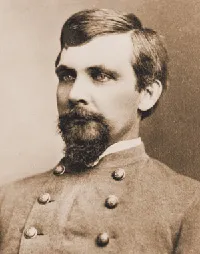

This excerpt from Valley Thunder describes the opening skirmishing of the battle, shortly after John Breckinridge has decided to take the offensive with his small Confederate force. Only a portion of the Federal army — the 18th Connecticut, 123rd Ohio and 1st West Virginia infantry regiments, supported by several artillery batteries and cavalry detachments, all under Col. Augustus Moor — is present and occupies a ridge to the north and northwest of New Market. The entire Confederate force is arrayed on higher ground to the south facing Moor’s position, sheltered from artillery fire at present on the reverse slope of the hill. At least four, and possibly all six, companies of the 30th Virginia Battalion have been deployed forward as skirmishers covering Breckinridge’s front. As the front of the hill occupied by the Confederates offers little shelter against Federal artillery fire, the commander of this part of the line, Brig. Gen. Gabriel Wharton, issues orders for his infantry to run down the hill to the shelter of the ravine at its base as quickly as possible, with little regard to order — the lines can be reformed at the base of the hill, Wharton orders. However, these orders are either not relayed to or are misunderstood by the commander of the VMI Cadet battalion, Lt. Col. Scott Ship, which results in a number of casualties as the cadets come under fire for the first time in the war.

Confronting the 30th Battalion were Companies A and B of the 18th Connecticut Infantry under Capt. William Spaulding. The 18th’s commander reported that “severe skirmishing shortly ensued” between the opposing lines. As the skirmishing intensified, wounded men began trickling to the rear. One of the injured was the 18th’s Joe Abbey, who had been shot in the back between the shoulder blades. A comrade jokingly remarked, “They must have fired from a balloon to hit you like that.” The wounded man was in no mood for humor and curtly explained that he had been lying prone on the side of the hill, his back exposed to enemy fire when the bullet found him. His company commander, continued Abbey, “sent me to the rear” to have his wound inspected and dressed. The spreading fight, and likely the pain brought about from his wound, confused the injured Connecticut solder. “Where in Hell is ‘the rear’?” he asked his comrade.

The noise and the movement of the troops also agitated a farmer’s animals. In addition to Confederate lead, the men of the 18th Connecticut also had to endure an “attack” from a herd of some 10 cows being chased by “a large black New Foundland [sic] dog [which] came charging along our line of battle. At first I thought it was a cavalry charge in flank,” remembered one Connecticut soldier.

While directing the fight from the skirmish line, Capt. Spaulding fell with a shot to the abdomen. The wound would prove mortal. The regimental chaplain recalled that Spaulding “was brave to a fault” and had been a conspicuous target on the skirmish line, giving encouragement to his men. “Are they driving us?” were the last words he uttered before dying.

The Confederates were indeed driving everything from their front — “sweeping like an avalanche,” as one Ohio soldier graphically recalled the initial push. The skirmishers of the 30th Battalion were engaged for only a very short time before Breckinridge ordered his infantry to advance. Within a few short minutes all three Confederate lines emerged over the crest of Shirley’s Hill. The manner in which they were deployed impressed the Federals who watched the parade-like advance — and convinced them that the Southern army was much stronger than it was in reality. Any deception on Breckinridge’s part was unnecessary, for the flanks of his extended line of battle stretched well beyond the flanks of Moor’s Manor’s Hill line, making the Federal position instantly untenable. “As soon as the Confederate support came in sight we were ordered to fall back,” one Connecticut soldier recalled.

Only at that moment, with three lines of Confederate battle striding toward him and his advance elements falling back, did Franz Sigel realize the mortal danger he faced. “It now became clear to me that all the troops could not reach the position close to New Market. I therefore ordered Colonel Moor to evacuate his position slowly ... and to fall back into a new position,” was how Sigel later spun the event. Moor’s line was withdrawn several hundred yards and reformed just south of Jacob Bushong’s house and barn, a retreat that abandoned the town of New Market to the advancing Confederates. As Moor fell back, the Federal commander sent orders to Brig. Gen. Jeremiah Sullivan to hurry forward with the rest of the army.

Moor’s new position was held by the 18th Connecticut on the right and the 123rd Ohio on the left, with von Kleiser’s battery in support on the Valley Pike. The 1st New York Veteran Cavalry, and likely detachments of other units, were placed in support of von Kleiser’s guns. The new line was even shorter than the previous one on Manor’s Hill. The other Federal troops on the field were being arrayed in line behind Moor just north of the Bushong farm, leaving Moor’s short line to act as a breakwater position to slow the Confederate attack and thus buy time for the main line of resistance to form. By placing his defensive position farther north, Sigel was shortening — albeit slightly — the distance the remainder of the army would have to cover to reach the battlefield.

Writing in Century magazine long after the war, Sigel sought to shift some of the blame for making a stand on this ground to the commander of his cavalry escort company. The new line on the Bushong farm was already beginning to take shape, explained Sigel, when “it was reported to me by Captain R. G. Prendergrast [sic], commander of my escort, that all the infantry and artillery of General Sullivan had arrived, the head of the column being in sight, and that they were waiting for orders.” In fact, only the 54th Pennsylvania and 12th West Virginia (Col. Joseph Thoburn’s brigade) had reached the field and were moving into position, all the while under hostile fire. Still absent were the 28th and 116th Ohio (Moor’s brigade) and DuPont’s battery.

As the Federal infantry scurried to find their new place in line, the artillery duel — which had fallen away when the Confederate attack stepped off — resumed. Supported by some of Imboden’s men on its right, the 30th Virginia Battalion pushed the Federal skirmishers out of New Market, clearing the way for the smooth advance of the main body. “The Rebels were in the town in force,” one resident recalled, “and occasionally we saw them lead by a wounded prisoner, or carry into shelter some dying comrade.”

Following Wharton’s instructions, the first waves of Confederate infantry pushed down Shirley’s Hill quickly, avoiding much of the hostile fire hastily aimed in their direction. Looking back from his position with the skirmish line, Maj. Peter Otey described the advance as “rather pell-mell.” Wharton was pleased with the swift moving advance, confident he had not lost a single man from his first line. The Corps of Cadets, however, either did not receive Wharton’s order or misinterpreted it. Instead of swiftly moving up and over Shirley’s Hill, the cadets tramped forward in perfect formation — presenting a perfect target for the Union guns. Otey, himself an 1860 VMI graduate, described the advance in a postwar speech: “Soon I saw the cadets who were in rear come over the little crest ... and down they came in as a beautiful and solid a line as I ever saw go across the parade ground.” Their disciplined advance impressed even the men in blue who witnessed it. “Nothing could be finer than their advance,” agreed Col. George Wells of the 34th Massachusetts.

Visually impressive it was, but the cadets’ parade ground tactics proved costly. “The Yankee gunners had gotten the exact range, and their fire began to tell on our line with fearful accuracy,” Lt. Col. Scott Shipp, commander of the cadet battalion, reported. “Great gaps were made through the ranks, but the cadet, true to his discipline, would close in to the center to fill the interval and push steadily forward.”

For most of the officers of the VMI cadet battalion, battle was nothing new. Many had served in the Army of Northern Virginia earlier in the war. This was not the case for the cadets. To them, combat was something new and utterly terrifying — far different from the glorious images of the romance of war they had conjured up while hard at their studies in Lexington. “We began to learn, much to our regret, that fighting was not as pleasant as we had anticipated,” Cadet John J. Coleman confided (and admitted) to his parents several days after the battle. “I saw wounded men stretched out for the first time,” Cadet Nelson B. Noland recalled, “and here for the first time it occurred to me that maybe we were not ‘playing soldier’ this time.” Another cadet, John S. Wise, also quickly discovered just how terrible fighting and warfare really was. “Down the green slope we went,” he recalled after the war.

He continued, “Then came a sound more stunning than thunder, that burst directly in my face; lightning leaped; fire flashed; the earth rocked; the sky whirled round, and I stumbled. My gun pitched forward and I fell upon my knees. Sergeant [William H.] Cabell looked back at me sternly, pityingly, and called out ‘Close up, men,’ as he passed on. I knew no more. When consciousness returned it was raining in torrents. I was lying on the ground, which all about was torn and plowed with shell.”

Wise was one of the first cadets wounded in the battle. About the same time he was struck, Prof. Capt. A. G. Hill, commander of Company C, and cadets Charles Read, James L. Merritt, and Pierre Woodlief also fell wounded. Capt. Hill, according to one observer, “fell like a log.” Merritt, who was injured by artillery fire, wrote to his father the next day that a shell fragment “knocked me about ten feet .... I thought the wound was mortal.” Another injured cadet stumbled across Woodlief, who had been hit in the leg. The wounded Woodlief, he wrote with no little disgust, was “whimpering like a child with a cut finger ... he thought his leg was shot off.”

The wounded Corp. Wise was the son of former Virginia Governor Henry Wise, who was now leading a brigade in General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The younger Wise had been detailed that morning with three other cadets — including Pierre Woodlief — to guard the Institute’s baggage. Their orders were unequivocal: remain with the wagon. “When it became evident that a battle was imminent,” Wise later wrote, “a single thought took possession of me … that I would never be able to look my father in the face again if I sat on a baggage wagon while my command was in its first, perhaps its only, engagement.” Having made up his mind to abandon the wagon and join his comrades in battle, Wise gave a short but stirring oration to his fellow guards, advising them that he planned to go to the front. “If I return home and tell my father that I was on the baggage guard when my comrades were fighting I know my fate. He [General Wise] will kill me with worse than bullets — ridicule.” When he finished speaking, all four cadets abandoned the wagon and set out for the front, leaving the baggage in the charge and care of its driver. Of the four cadets detailed to guard the wagon, one would be killed and two wounded in a battle they joined by choice.

Learn More: Charles R. Knight's book is available for purchase

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

841

531