Victory at Brandy Station

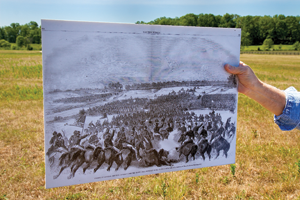

In the summer of 1987, historians and other activists concerned about the rapid loss of battlefield land formed the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites (APCWS) — a precursor to the Civil War Trust. The new organizations came not a moment too soon for Brandy Station.

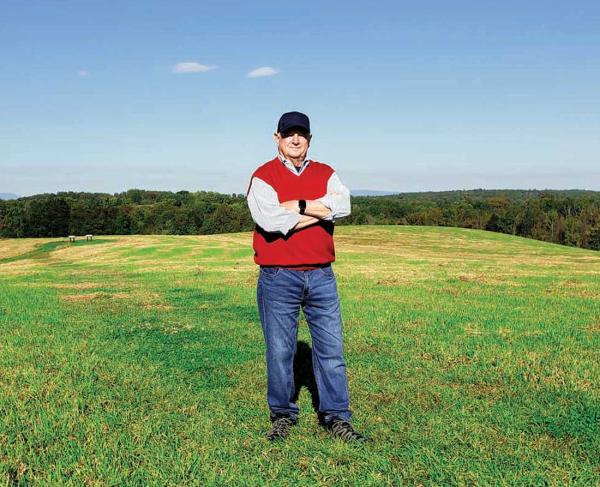

Among those early preservation advocates was former Marine and federal investigator Clark “Bud” Hall, who had spent significant time walking the Brandy Station Battlefield, mapping troop positions, plotting specific points and cultivating close relationships with many local landowners along the way. These friends alerted Hall as their neighbors increasingly began selling their land. Like a line of dominos, a significant portion of farmland comprising the Brandy Station Battlefield fell, piece by piece, into the hands of California real estate investor Lee Sammis. His buying spree signaled to Hall that the hallowed ground was in jeopardy. Hall confronted the developer, who, in an attempt to quell any objections to the ultimate plan for the property, told him it was a family investment intended to be used for farming.

Despite these assurances, preservationists could see the writing on the wall: if Brandy Station were to be saved, there would be a struggle. Indeed, Sammis soon announced that his company, Elkwood Downs Limited Partnership, would build a large-scale corporate office park on the Brandy Station Battlefield. APCWS, concerned citizens, preservationists and local landowners quickly joined forces to create the Brandy Station Foundation in response to the threat. As the coalition gained steam, high-profile names came aboard, specifically Tersh Boasberg, one of the nation’s top preservation attorneys, and Washington lawyer Daniel Rezneck. Their involvement legitimized the organization in the eyes of many by providing much-needed legal footing, thrusting the APCWS and the Brandy Station Foundation — and with them, the modern-day battlefield preservation movement — into the national spotlight.

After years of controversy, Elkwood Downs filed for bankruptcy, leaving its development vision unfulfilled. But pause for celebration was brief. New developers targeted the hallowed ground as an ideal site for a Formula One racetrack and proposed plans to build on 515 acres of the battlefield, a construction project of such magnitude that it would have meant complete destruction of the historic land. Preservationists mobilized to begin fighting the racetrack, but providence struck first — insufficient planning and lacking infrastructure forced the developer to declare bankruptcy and abandon its plans.

After two close calls, the coalition of preservationists acted quickly to ensure the preservation of the battlefield by purchasing the property. Ultimately, and at a cost of more than $6 million, APCWS bought 944 acres from Sammis in 1997. The acquisition was a huge step forward in preserving the battlefield, but the process was far from complete and much more historically significant land remained to be saved. But, as is often the case, success bred success and, gradually, more properties were added. A particular highlight of the preservation process came in 2003, the 140th anniversary of the battle, when the Civil War Trust and the Brandy Station Foundation unveiled the Brandy Station Battlefield Park, comprised of interpretive signage, hiking trails and a driving tour. By the end of 2012, on the eve of Brandy Station’s sesquicentennial year, the Trust and its partners had protected more than 1,800 acres of the battlefield through outright purchase and conservation easement, making it one of the organization’s greatest success stories.

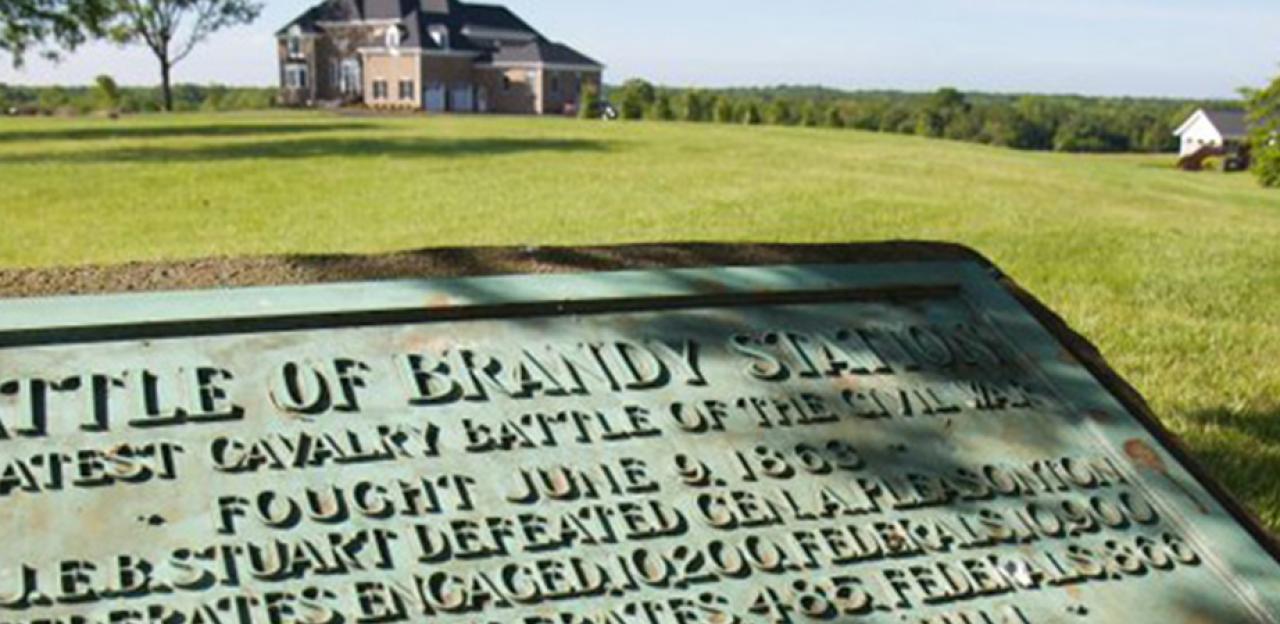

Still, something was missing. Despite having made several overtures over the years, Trust officials had been unable to make any inroads toward securing the battlefield’s most visible feature, the heights of Fleetwood Hill — the crest of which was occupied by a pair of large, modern homes. Nonetheless, periodic discussions with the landowners continued until, eventually, a breakthrough occurred. In May 2013, the Trust kicked off a $3.6 million campaign to purchase 56 critical acres atop Fleetwood Hill.

With such a lofty goal before it, the entire preservation community rallied behind the Civil War Trust in its quest to purchase the property. Particularly notable contributions — both financial and logistical — came from partner groups the Central Virginia Battlefields Trust, the Journey Through Hallowed Ground and the Brandy Station Foundation, as well as from numerous private citizens. Generous matching grants from the federal American Battlefield Protection Program and the Virginia Civil War Sites Preservation Fund were also instrumental in securing the full purchase price of the property to complete the transaction in August 2013.

Although pockets of land remain that would, ideally, be protected and integrated into the existing park, preservationists agree that the heart and soul of Brandy Station is now protected, and this great battlefield will go down in history as a one of the preservation movement’s great victories. As Trust President James Lighthizer remarked, “Development of this historic property would have diminished all that has been accomplished at Brandy up to now. Protection of Fleetwood Hill turns a success into a preservation triumph.”

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

866

433