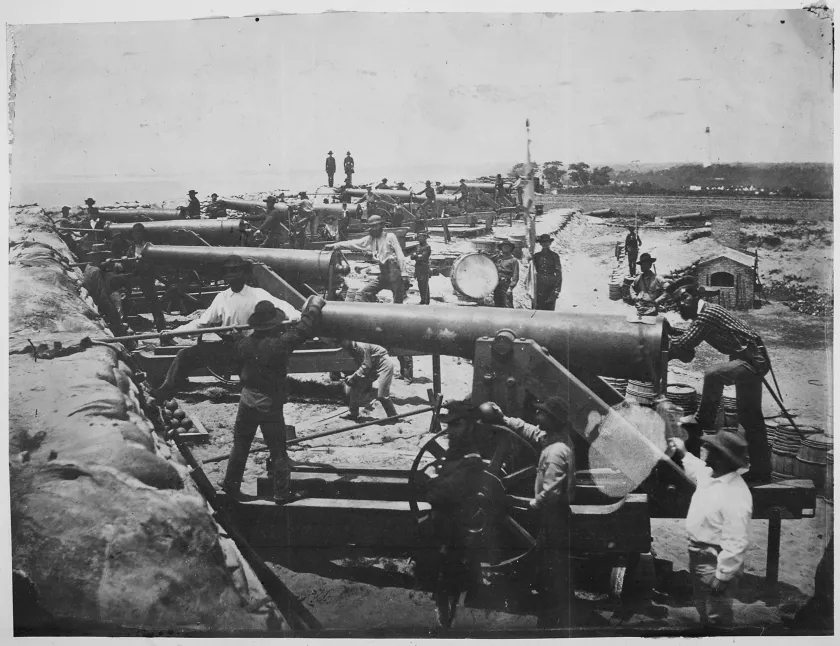

"Columbiad guns of the Confederate water battery at Warrington, Florida (entrance to Pensacola Bay)" by the United States Department of War 1863-1865

During the secession winter of 1860-1861, members of the Regular Army stationed at federal forts in the south, and civilians in the surrounding localities, were on edge. While some wanted to avoid military conflict, supporters of the newly formed Confederate States of America and its fledgling government believed that they had established a legitimate nation that should control the coastal fortifications within its borders. Between the election and inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, President James Buchanan, a Democrat from Pennsylvania whose administration was plagued by the sectional divisions of the 1850s, was a lame-duck. Buchanan believed that while secession was not necessarily legal, the federal government could not stop it. The incoming Lincoln administration, and several Regular Army officers stationed in coastal fortifications in the South, however, wanted to retain the forts for the U.S. government since they had always been federal – not state – property, and since surrendering the forts to the Confederacy would violate the oath that soldiers took upon enlistment in the U.S. Army.

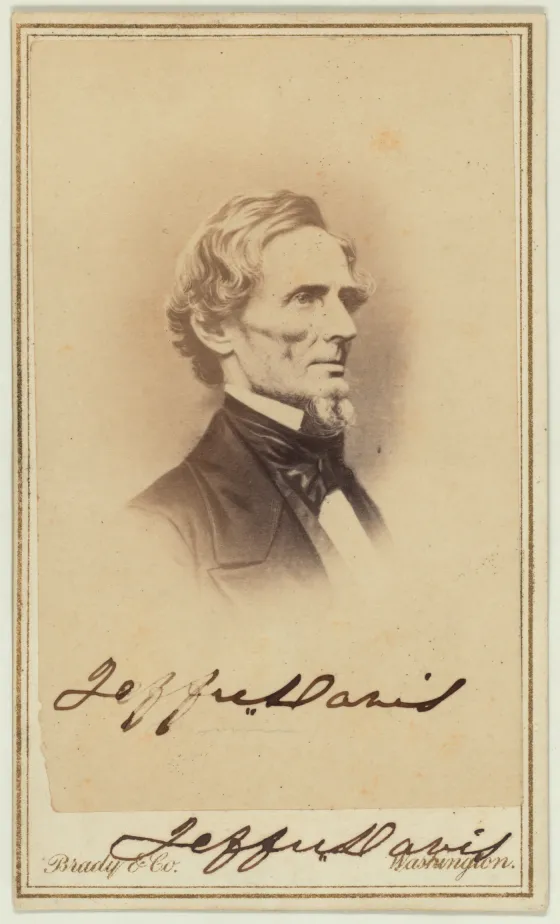

Once Confederate troops opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861, leading Lincoln and Confederate President Jefferson Davis to call for volunteers to defend their banners, the struggles of soldiers in other critical forts across the Southern coast, particularly the Gulf, received coverage in newspapers and figured into Union and Confederate military planning given their importance in defending both shipping and the mainland. Pensacola, Florida’s deep-water harbor with fortifications, commercial lumbering mills, and a significant navy yard that boasted docking, supply, and shipbuilding facilities would be an asset to the power that controlled the town. The town was also an important railroad hub: It was the southern terminus of the Alabama & Florida Railroad which stretched to Montgomery, Alabama, and the Pensacola & Mobile Railroad which ran from the Perdido River to a junction with the Alabama & Florida Railroad fourteen miles north of the city.

Florida’s Gulf Coast was crucial to the U.S. economy, and its forts comprised the first line of defense against any potential encroachment from European powers. Southern planters and producers transported their goods to port cities along the Gulf Coast from New Orleans to Pensacola, and Pensacola’s Navy Yard, established in 1826 and its system of fortifications that included Forts Pickens, Barrancas, and McRee watched as ships passed into and out of Pensacola, or sailed on the Gulf’s open waters past the panhandle down to the Florida Keys, and out to the Atlantic for coastal U.S. and/or international trade.

Pensacola was well-defended with three forts: Pickens, McRee, and Barrancas which included the Advanced Redoubt and Battery San Antonio (also known as Water Battery) keeping watch over the harbor. Possession of Pensacola was critical to maintaining control of the Gulf and both Union and Confederate soldiers vied to take or keep possession of this critical town, its defenses, and its military and economic assets all the while staving off boredom, the trials of a tropical climate, and the threat of disease. With the passage of time, however, these Gulf Coast forts at Pensacola and elsewhere faded from popular memory, overshadowed by active military campaigns. But the U.S. Regular soldiers stationed in the city’s surrounding forts and the Confederate troops who aimed to take them, understood that war could have started at Pensacola and feared that it could become the focus of a sustained active campaign.

Amidst sectional tensions and the secession of the lower-south states, Confederate politicians, civilians, and soldiers coveted control of Pensacola’s forts to bolster their national defenses and wanted its navy yard to help the Confederacy build a fleet from scratch. The Lincoln administration believed that the federal government was supreme and should retain the forts, which were federally funded and built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. According to Attorney General Edward Bates, the forts that surrounded Charleston, South Carolina were symbolically significant since they stood in the epicenter of secession, but they lacked national economic and defensive significance. On March 15, 1861, Bates advised Lincoln against provisioning Fort Sumter and recommended that, if Sumter was evacuated, the “more Southern forts – Pickens, Key West, &c – should, without delay, be put in condition of easy defence against all assailants.” He also advised that the “whole coast from South Carolina to Texas” be “as well guarded as the power of the Navy will enable us,” recognizing the economic and military importance of this region. Bates revised this recommendation on March 29, 1861, telling Lincoln that “Fort Pickens and Key West ought to be reinforced and supplied, so as to look down opposition, at all hazards” whether “Fort Sumter be or be not evacuated.” Bates’s communication, and local dynamics at Pensacola, set the stage for sectional tensions to potentially boil over into war on the Florida Panhandle. Pensacola’s fortifications were crucial to the defense of this strategic commercial and military location.

Despite the Lincoln administration’s outlook and the threat of secession, U.S. officials did not reinforce Pensacola’s forts, leaving troops stationed in them to fend for themselves. On January 8, Florida militia under Colonel William Chase, one of the engineers who designed Pensacola’s defenses, demanded that U.S. troops under command by Lieutenant Adam Slemmer (in the absence of future Confederate Brigadier General and Commissary General of Prisoners, Major John Winder) surrender Fort Barrancas, but Slemmer deterred the would-be assailants with warning shots. Ultimately, Slemmer thought his position untenable and considered Fort Pickens more secure. Pickens had not been garrisoned since the Mexican War, and only an ordnance sergeant and his wife occupied Fort McRee, which was used to store ammunition. On January 10, 1861, the day that Florida seceded from the Union, Slemmer moved his fifty-one U.S. Regular troops stationed at Fort Barrancas, which overlooked Pensacola Bay, to Fort Pickens after spiking their guns. U.S. troops also abandoned Fort McRee after disabling its guns and tossing its gunpowder into the harbor.

State troops from Florida and Alabama thus held Forts Barrancas and McRee, in addition to the Navy Yard. Slemmer deemed Fort Pickens was more significant, however, since it overlooked the bay and the Pensacola Navy Yard from its location on Santa Rosa Island. U.S. soldiers bolstered defenses at the run-down fort, anxiously anticipating that Florida state troops may attempt to take Fort Pickens as they had two of Florida’s Atlantic forts: Marion in St. Augustine and Clinch at Fernandina. These men had reason to worry since, lacking reinforcements, they witnessed Confederate troops occupy Forts Barrancas and McRee and watched as they bolstered their lines. On January 15, Confederate soldiers pressured Slemmer to surrender Fort Pickens. Slemmer refused, but not without striking a deal on January 28: In exchange for a Confederate promise not to attack, U.S. troops would not reinforce Fort Pickens.

General Winfield Scott, however, gave confidential orders for U.S. Regular troops under the command of Captain Israel Vodges of the 1st Artillery to head for Pensacola on the sloop U.S.S. Brooklyn. Stephen Mallory, former U.S. Senator who became the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, learned of the destination of Vodges’s men and attempted to get Buchanan to stop them. Buchanan, however, allowed the ship to sail to Pensacola but promised Mallory that they would not land unless Fort Pickens was attacked. Vodges’s men remained on the Brooklyn until March when, on March 12, Scott and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells, again secretly ordered Vodges and his troops ashore. These orders did not reach Pensacola until March 31, however, and were ultimately scuttled since Captain Henry Adams of the U.S.S. Sabine, anchored off Fort Pickens, considered them an act of war.

Attempts to reinforce Pensacola did not cease, however. Lieutenant David Porter aboard the warship U.S.S. Powhatan soon sailed for Pensacola, and Vodges and his troops disembarked on the night of April 11, shortly before Confederate troops bombarded Fort Sumter, officially starting the war. Additional Union troops, Companies C and E of the 3rd Infantry and Companies A and M of the 2nd Artillery, under Colonel Harvey Brown landed on April 16 and 17 and held the fort into the summer of 1861, bolstered by the U.S. Naval blockade of Pensacola harbor. Brown’s men got to work strengthening the fort’s defenses and unloading supplies from ships.

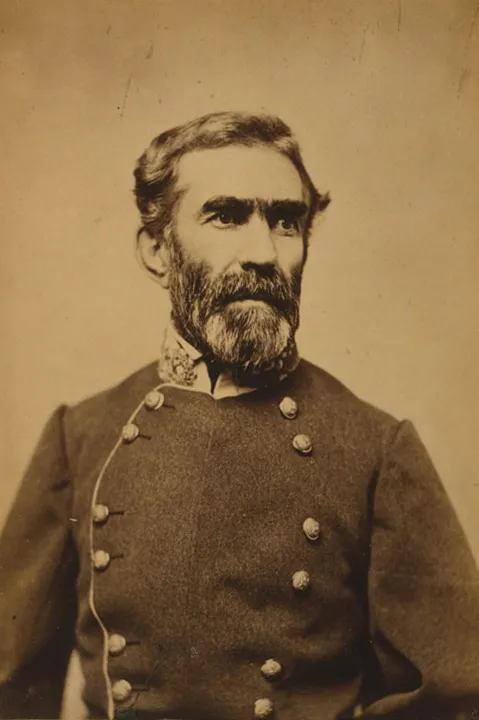

Meanwhile, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the Confederate War Department ordered Davis’s friend, General Braxton Bragg, to command Confederate troops in and around Pensacola. Bragg received these orders on March 7, arrived at Pensacola on March 11, and established his headquarters at Fort Barrancas. Confederate troops established a line that stretched from Bragg’s headquarters to Fort McRee. By the end of March, Bragg commanded approximately 1,100 officers and men and the Confederate War Department requested additional troops, up to 5,000, from the governors of Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, and Florida. By the second week of April, Bragg had 5,000 men in the ranks.

Bragg aimed to take Fort Pickens but lacked sufficient siege guns and would have to rely on surprise. He devised a plan for a nighttime attack on April 11, during which soldiers would row across the bay, climb Fort Pickens’s walls, and storm its Union defenders. This plan was never executed, however. A local reporter for a Pensacola newspaper spoiled the plot, bringing reinforcements from U.S. ships to come to Fort Pickens, forcing Bragg to halt his plans and imprison the reporter.

After this failure, Jefferson Davis hoped that a summertime yellow fever epidemic would force Union soldiers to evacuate the fort, but the disease did not break out in the summer of 1861. Instead, Union and Confederate defenders of Pensacola eyed each other suspiciously, hoping to have the opportunity to trade labor on fortifications for a chance to prove themselves in battle. The Lincoln administration sent additional naval forces to Pensacola in May when the steam frigate Niagara, under the command of Captain William McKean, arrived at Santa Rosa Island on May 25 after a twenty-day journey. In late June, Colonel Billy Wilson’s 6th New York Volunteers (Wilson’s Zouaves) arrived at Pensacola. By this time, both Union and Confederate forces in and around Pensacola were formidable and both sides coveted ultimate possession of the town and its defenses.

Opportunities for valor came in September and October 1861. On September 2, Union raiders scuttled a drydock at the Navy Yard which Confederates had planned to sink into the channel to obstruct Union offensives. Then on September 14, Union sailors and marines burned the Confederate ship Judah, which was docked at the Navy Yard, and spiked a Confederate Columbiad cannon at a nearby battery. The raid resulted in three Union soldiers killed and thirteen wounded, while Confederates suffered three dead and an unknown number of men wounded.

The Union garrison inside of Fort Pickens feared through October 1861 that Confederate troops would attack Fort Pickens, and they were correct. In retaliation for the burning of the Judah, Bragg ordered a surprise assault on Santa Rosa Island on October 9 by approximately 1,000 troops under Brigadier General Richard Anderson. During the night of October 8, Anderson’s men boarded barges and sailed across the bay, landing four miles east of Fort Pickens at midnight. Confederate troops marched three miles towards the fort and encountered the camp of the 6th New York, who put up a brief fight before a panicked retreat. Anderson lost the element of surprise with daylight breaking and Confederate troops retreated during and after a skirmish with Union assailants from the Fort Pickens. The Battle of Santa Rosa Island cost the Union 67 casualties (killed, wounded, missing, or captured), while Confederates suffered 87 casualties.

In late September, Flag Officer William McKean succeeded Flag Officer William Mervine as commander of the Gulf Blockading Squadron and planned a combined attack on Confederate harbor defenses. On October 11, McKean’s flagship, Niagara arrived at Santa Rosa Island, and Union troops prepared to confront Bragg’s men which, by this point, had strengthened to approximately 7,000. On November 21, the U.S.S. Niagara and the U.S.S. Richmond were prepared to cooperate with Col. Brown in a bombardment of Confederate defenses. On November 22-23, 1861, U.S. guns at Fort Pickens, accompanied by the two U.S. warships, bombarded Fort McRee. Confederates returned fire in an artillery duel that lasted over eight hours and inflicted significant damage to Fort McRee and the Navy Yard, but resulted in minimal casualties.

A quiet December followed this bombardment, but Bragg realized that challenges were forthcoming. After the Battle of Santa Rosa Island and the Union’s bombardment in late November 1861, Bragg faced supply shortages and men reluctant to reenlist as initial terms were short. The Bounty and Furlough Law that the Confederate Congress passed on December 11 inspired some reenlistments since it offered a $50 Bounty and 60-day furlough with transport home if men reenlisted. On January 1-2, 1862, Union troops unleashed another artillery duel and Confederates reciprocated. The minor affair resulted in the burning of a storehouse at the Navy Yard. After this action, troops at Pensacola settled into a stalemate as Union military focus shifted further west, causing Confederate attention to follow.

Elsewhere on the Gulf, the Union army achieved more significant gains. Troops under Major General Benjamin Butler landed at Ship Island, Mississippi to bolster the blockade of the Mississippi River and serve as a base to target Pascagoula, Mississippi and Mobile, Alabama. Confederates thus debated abandoning Pensacola – a position that gained more support when Union troops took Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862, and as Union troops gained ground in Kentucky, and troops under Flag Officer David Farragut captured New Orleans. Confederate soldiers at Pensacola started to shift west to help combat the tightening Union blockade. In February, Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin directed Bragg to send his troops to Tennessee, and Bragg was transferred to Mobile.

General Samuel Jones took command at Pensacola and was ordered to withdraw as soon as possible. Jones was to salvage guns and munitions for the Confederacy by moving them and supplies to Mobile, and to destroy resources useful to the enemy. By mid-April 1862, only approximately 1,500 of 6,500 Confederate troops remained in Pensacola and the remainder prepared to leave, albeit not without damaging supplies that might have been useful to the Union. Confederate soldiers thus stripped the Navy Yard of its machinery, destroyed boats, sawmills, lumber, and railroad tracks, while preserving the customs house and commissary storehouse. Finally, on May 9, 1862, Confederate troops evacuated the town of Pensacola and cavalry burned the Navy Yard, storehouses, an oil factory, boats and steamers as civilians fled for safety.

Union soldiers took possession of Pensacola on May 10 and occupied the town and its forts throughout the rest of the war. Rear Admiral David G. Farragut determined that the Navy Yard could be repaired and could serve as a depot for his West Gulf Blockading Squadron and used the Yard as an operational base for the war’s remainder. Fort Pickens also served as a Union base for military operations, as did Fort Barrancas – U.S. troops used these sites to launch operations into West Florida and Alabama and Union troops maintained a constant garrison in Pensacola though their numbers diminished by 1863 as military focus shifted to the Mississippi River.