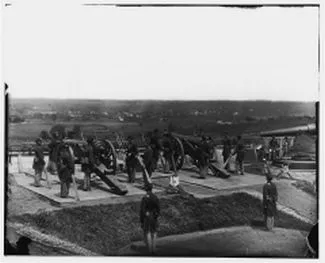

By the close of the Civil War, Washington, D.C. was the most heavily fortified city in North America, perhaps even in the world. According to the report of the army’s official engineer, her defenses boasted 68 enclosed forts with 807 mounted cannon and 93 mortars, 93 unarmed batteries with 401 emplacements for field guns and 20 miles of rifle trenches plus three blockhouses. Moreover miles of military roads, a telegraphic communication system and supporting infrastructure — including headquarters buildings, storehouses and construction camps — ringed the city. Thus, “the finest existing example of the system of defenses based upon a series of detached forts connected by a continuous trench line” contributed to a sense of “seeming impenetrability.” Yet, that system came close to failing at a critical juncture in the war that might well have cost President Abraham Lincoln his life, the Union its war and the country her national unification. This unsung story finds scant attention today in history books or at the various parks preserving the remains of some 22 fortifications, including Fort Stevens, site of a critical battle during Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s 1864 attempt to capture the American capital.

Even today, the nation’s capital is guarded by an air defense and homeland security system perpetuating man’s age-old tradition of protecting seats of power and governance. And the story of defending Washington actually begins in the sorry tale of two inadequate river forts, Great Britain’s successful capture and burning of the nascent capital in August 1814 and a tradition of peacetime pecuniary neglect of national security. At the time of Lincoln’s election and the Secession Winter, and even through his inauguration, the bombardment of Fort Sumter and his subsequent call for volunteers to suppress rebellion, Washington possessed only a namesake river fort, with virtually no armament and manned by a drunken ordnance sergeant. The city itself had a militia of questionably loyalty supplementing a minuscule group of regular Army ordnance technicians and Marines for protection. True, there was the Navy Yard, but it was given to manufacture and repair and was no harbor bristling with ships and guns. A quick infusion of Army regulars from frontier and other posts and the intrepid leadership of the army’s commanding general, the aged Winfield Scott, ensured Lincoln’s safety. The eventual arrival of northern militia volunteers allowed the first rudimentary fortifications to be built on the “sacred soil of Virginia.” From little more than bridgehead protection would emerge engineer Brig. Gen. John Gross Barnard’s formal Defenses of Washington system. As chief engineer, Barnard was directed to design and build forts to defend Mr. Lincoln’s City.

The make-weight crisis came with the Union military disaster at First Manassas in July 1861. A combination of Lincoln’s fast-developing paranoia about the city’s safety, the arrival of a new general-in-chief, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan and a plethora of military and civilian labor available in the fall and winter meant that the U.S. government became serious about protecting the city as a political symbol of Union. Washington (and now-occupied Alexandria, Va.) became the logistical hub and staging area for operations against Confederate forces in Virginia. In fact, Washington forts countervailed similar fortified rebel camps at Centreville, Leesburg and Dumfries on the Potomac. The navy’s fledgling Potomac Flotilla kept the river route to the capital open against Confederate batteries downriver, while two armed camps stared at one another at a distance of thirty miles. The Confederate withdrawal to the south and McClellan’s ambitious Peninsula Campaign altered the impasse that had emerged in the spring. By the summer of 1862, 48 forts and batteries protected the city, although by no means in any systematic way. At least, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington had rudimentary protection and a mind-set of defense. It also had a new and controversial zeitgeist that would henceforth determine how the war in the east would be fought and how the capital would be defended and, almost, lost.

This spirit of the moment represented an abiding contest between Lincoln and his generals that would govern affairs for the remainder of the war. It keynoted a theme generally often overlooked in Civil War historiography, that Lincoln and his administration wanted secure protection for Washington — forts, guns, garrison etc. —before any field army undertook a campaign against the Confederates in Richmond. Army commanders, in particular, identified the field army — the maneuver force personified by the Army of the Potomac — on the offensive against Richmond her defenders as the optimal protection for the Nation’s Capital. Barnard and his engineers, however, saw the situation differently: a symbiotic relationship where the forts and garrisons were a shield, working hand in glove with the maneuverable army or sword. Victory-hungry generals saw little need to lavish scarce resources of men and material in static defenses; but then, neither did Lincoln, who simply demanded suitable protection for Washington.

Such controversy continued for two campaigning years. The engineers built and constantly improved Washington’s fortifications using both white and black, soldier and civilian labor. Ordnance men constantly shifted cannon while technically proficient “heavy artillery” units specifically recruited for Washington’s defenses learned their trade of trajectory and distance computation, surveyed the countryside presided over by the frowning heavy cannon, and fraternized with local civilians. It was a pleasant existence for the “spit and polish” white-gloved garrisons, broken only by periodic scares from Col. John S. Mosby’s partisans or Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s northward expeditions.

In fact, Lee came close to challenging, if not capturing, Washington’s defenses — both the field army and the field fortifications — after the Battle of Second Manassas. The long-forgotten battle of Chantilly, the remnants of the defeated forces of John Pope and Lee’s almost mystical inhibition about the impregnability of Washington’s defenses gave him pause and, like after the Battle of First Manassas, the moment of decision slipped away. However, the appearance of Confederates so close to the city panicked Lincoln and his generals once more, particularly as Lee’s host slipped into Maryland. Many saw the specter of 1814 all over again, when the enemy swooped in from the north through Bladensburg to plunder the city. Fortifications suddenly grew stronger thanks to soldier and contract labor. A free black landowner watched her house crumble beneath soldier axes and sledgehammers as Fort Massachusetts was expanded and became Fort Stevens. She always claimed that she had been promised a “great reward” for her sacrifice for military necessity by a tall, black-clad stranger, but that Lincoln’s promise never materialized. But, a rejuvenated Army of the Potomac, once more under McClellan’s steady hand, regrouped, Lee was thrown back at Antietam and the capital was saved. The war receded once more to Central Virginia and the road to Richmond. The same thing happened again the next year. Washington and the government panicked, as Lee circumvented the capital on his march into Pennsylvania, leaving behind much of his army on the bloody fields of Gettysburg.

By mid-point in the struggle, a War Department Commission, led by Barnard, had dissected the strengths and weaknesses of what had become a vast system of defenses for Washington, as well as the needs and costs for maintaining and improving those fortifications. Civilian labor now provided the means for erecting more earthworks, barracks, sheds and storehouses. Civilians also constructed elaborate river works at Fort Foote (which supplanted the aged Fort Washington) to deter naval attacks — a threat not so much from the Confederates as from European powers seeking to intervene. The commission calculated the need for infantry garrisons numbering 25,000 men, plus 9,000 trained artillerists, a cavalry force and an additional 25,000-man maneuver force — all separate from the campaigning Army of the Potomac. In typical military fashion, the numbers were completely unrealistic given manpower deficiencies and draconian efforts to fill the armies of the Union proper. In terms of the mission of defending the city, however, the figures were reasonably realistic. Yet, as the months of 1863 waned without a serious direct threat to the capital, predicable complacency prevailed. After all, the city had 60 forts, 93 batteries and 837 guns together with 23,000 garrisoned men in position to defend her. Wasn’t that sufficient?

Matters looked good on paper. A now-connected system of fortifications existed by which every important point (at eight hundred to 1,000 yard intervals) was occupied by an enclosed fort of some type. Every important approach or depression not necessarily commanded by such a fort was swept by a battery for field guns (to be emplaced in an emergency by arrival of batteries of the maneuver army). Rifle-pits for two ranks of men connected the forts around the perimeter of the city, except to the east of the city beyond the Anacostia River. This was the zone of least threat, even though an enemy could knife between forts and take commanding artillery positions along the ridge overlooking the Navy Yard and within firing distance of the capitol. Yet, this point in time became the moment of maximum danger, as newly arrived General-in-Chief, Ulysses S. Grant led the Army of the Potomac in spring and summer campaigns against Lee and Richmond. Dismissing Lincoln’s concern for the defense of Washington, Grant nearly sacrificed the whole game, as it turned out.

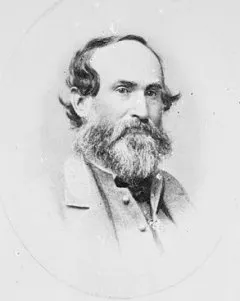

Grant, like McClellan and the other army commanders adhered to the notion that the best defense was a good offense. The Army of the Potomac needed trained manpower and to his mind, the defenses of Washington, in part, could provide it. So all the “Heavies” and the infantry and cavalry departed the forts for the field, replaced by semi-invalid Veteran Reserves, trainees, 100-day levies and a small cadre of experienced troops who escaped the dragnet. Ever-mounting casualty lists from the Overland Campaign only served to drain even more from Washington’s protection despite admonitions from the engineers, and the ever dangerous Robert E. Lee sensed opportunity. In the early summer he dispatched Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early on the war’s most daring and ambitious attempt to capture Washington. This story too has seemingly escaped the pages of history as possibly the decisive moment in the Civil War. Of course, it remains a central point in the story of the defenses and defending the city.

Confederate authorities felt that another offensive north of the Potomac could shock the war-weary North in a presidential election year. Lee was more focused, thinking Early’s expedition could relieve pressure upon his own forces in the Richmond-Petersburg lines. He directed Early to capture Washington if he could, cut rail and telegraph communications around Baltimore and free the thousands of prisoners purportedly held at Point Lookout in southern Maryland. It was a tall order that depended upon speed, deception and, ironically, the weather. Grant and the Army of the Potomac had no inkling of the daring raid until it was almost too late. Leaving Richmond in late June, Early saved Lynchburg and Lee’s logistical lifeline, and then swiftly transited the Shenandoah Valley, crossing into Maryland by July 7. Two days later, he ransomed the town of Frederick for $200,000 and fought a pitched battle with a motley array of Federals assembled by VIII Corps and Middle Department commander Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace (who went on to write Ben Hur) on the banks of the Monocacy River, just south of town. The battle — now one of the National Park Service’s flagship sites — resulted in decisive Confederate victory, but at heavy cost to Early’s legions and a delay in his timetable.Monocacy, aptly termed “the battle that saved Washington,” cost Early a whole day’s march time and was one of two episodes that determined the fate of the capital and the nation that summer.

Early won the battle but lost the ensuing race to get to the capital before, freshly alerted to the dire threat, reinforcements could arrive in the city, rushed by water from City Point, Va. A panicked government, a confused command setup and ill-matched troop units, coupled with refugees and an overcrowded city populace made for an unstable situation in anticipation of Early’s arrival. But, the main story was the combination of the delay and losses caused by the Battle of Monocacy, temperatures reaching the mid-nineties and troop columns enveloped in dust. Lincoln wired hysterical Baltimoreans to be “vigilant but keep cool” as he hoped neither city would be taken. Still, he really had no control over the situation. Nor, it seems, did Early, as it took his men a day and a half to reach the Washington suburbs. Hasty reconnaissance suggested the need to shift eastward in order to break through the defense system and more time was wasted marching across the Federals in plain view from Rockville, Md., to the Seventh Street road. Sharp-eyed Federal signalers caught sight of the dusk clouds and what they portended by the time Early’s advance elements appeared before Fort Stevens about mid-day on July 11. The general was up to the task at hand; his army was not. Strung out beside the road for miles in the heat and dust, they were simply too tired and thirsty to mount the decisive attack Early needed. The Confederate force might at this point have been successful at breeching the Yankee lines, but instead merely settled into cooling bivouacs at Silver Spring and in the vicinity of today’s Walter Reed Army Medical Center while their leaders studied Washington’s fortifications before them.

Union lines appeared strong but feebly manned. All that Confederate officers could discern through binoculars were citizens and militia manning the ramparts. Still, a headlong rush seemed inopportune in the heat, so the raiders resorted to skirmishing while the defenders remained content to await reinforcements. It was a curious standoff in retrospect. Perhaps by this stage in the war nobody wanted to take chances. Certainly the soldiers were in no particular mood to sacrifice themselves. One who was, however, appears to be President Lincoln, who arrived by carriage with an official party and a host of curious. From the Potomac east to the rail tracks to Baltimore, the line of Washington’s forts became the battle sector. Sharpshooters peppered ramparts, Lincoln and his wife Mary ostensibly visited the wounded in the fort’s hospital but nobody made a move toward pitched battle on July 11.

The next day would be critical; the decisive moment for both sides. Dawn brought the illusion that veteran reinforcements in faded blue had arrived on the Union lines. In reality, these merely dismounted cavalry and invalids. Confederate leaders again hesitated. Ironically, hastily improvised cavalrymen thrust into the rifle pits deceived Early long enough for the real reinforcement from the VI and XIX Corps to arrive at Washington’s wharves and march out to bolster the defenses. Early now realized his precarious position. Isolated north of the Potomac with pursuers coming in on his rear from the west, it looked like would be unable to complete his missions of freeing prisoners, disrupting communications and — above all — capturing Washington. “We didn’t take Washington,” Early told his staff officers, “but we scared Abe Lincoln like Hell.” But now he must escape; Lee needed his men. Skirmishers would have to buy him time until night would permit withdrawal.

Meanwhile, the persistence of the Union Commander-in-Chief’s desire to view the skirmishing from atop Fort Stevens’s parapet nearly achieved unexpected consequences for Early and the Confederacy. When a surgeon nearby went down with a sharpshooter’s bullet, Union commanders realized this nonsense of a president being shot at had to stop. He could be killed, the battle lost and the war altered all with the crack of an Enfield rifle in the hands of a butternut sharpshooter. So the army generals ordered an advance by several veteran brigades from the Army of the Potomac. It was all very military — flags flying, lines straight — and Lincoln loved it. However, 10 percent of the attackers went down in the melee as rebels rushed down from their camp sites and the late afternoon produced a new stalemate, out beyond the fortifications, in the no-man’s land that today features urban neighborhoods and the outskirts of Walter Reed, before Early slipped away under cover of darkness.

The bloodletting created the semblance of Union battle victory in the only Civil War battle inside the District of Columbia. Washington’s forts had held and performed their designated task. The boom of heavy cannon, the crack of musketry, the clatter of arriving and shifting maneuver forces and the only time that a serving American president had come under enemy fire while in office all marked the so-called “Battle of Fort Stevens.”

Monocacy, Fort Stevens and Early’s raid symbolized the continuing peril of the Union — notwithstanding the result. In London, newspapers proclaimed that the Confederacy seemed more formidable an enemy than ever. Grant had been caught off-guard and nearly lost the capital by neglect and Lincoln’s political fortunes sunk to their lowest depths. The threat to Washington provided a wake-up call that changed the direction of the war. Grant continued his tenacious hold on Lee, even though Early remained a hovering threat in the lower Shenandoah until Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s Valley campaign ended that annoyance in September and October. That, together with Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta, shifted the fortunes of war and secured Lincoln’s reelection. As the war wound down, the engineers and garrisons in Washington’s forts continued to expend money and labor bolstering the works. And, after Appomattox, they maintained some of the forts as long as possible conflict threatened with France over Mexico.

Gradually, landowners reclaimed the ground and cut the timber that buttressed walls and structures in the forts. The military collected cannons, tools and equipment inside the forts, sending them back to depots downtown. Engineers wrote reports seeking to prevent the disbanding of all the forts and the recurrence of an unprotected national capital. Yet, the re-united nation wanted to forget war and erase military expenditures for any large standing army or navy. The books closed formally on the vast wartime endeavor on June 14, 1866 and authorities never again considered extensive field fortifications to defend Washington. Later on in the century, however, new river batteries were constructed as protection against foreign naval intrusion. Then, they too receded into history as technology and changing dimensions of national security rendered them obsolete. In the 1860s, engineer Barnard considered his Civil War brainchild the equal of any European fortification system of its time.

Defending Washington had expended $1.4 million of the war effort and kept back an average of 20,000 men from the Army of the Potomac at any given time. Grant’s insensitivity to Lincoln’s paranoia about the city’s protection in the spring and summer of 1864, coupled with the president’s failure to sufficiently dent Grant’s focus on the offensive, as he had two years earlier with McClellan, carried the nation to the brink of disaster by July. The “what ifs” that subsequently accompanied Early’s appearance — possible death or capture of Lincoln, the capture of the capital, whether temporary or permanent, and the cause for Grant’s lifting the Richmond-Petersburg siege during the critical election campaign — all remain wondrous to contemplate today. Standing today where Lincoln stood in 1864 atop the Fort Stevens parapet (a spot well-marked by a stone marker and bas relief), one must marvel why posterity has never declared this singular event one of the pivotal episodes (or even Confederate “lost opportunities”) of the Civil War. If Lincoln had been killed or the capital lost, George B. McClellan might have been elected, possibly leading to a military Caesar taking charge during a horrendous of civil-military crises, determining the postwar course of the nation — or nations. We do well to ponder the effect since it took three critical civil rights amendments to render permanent Lincoln’s emancipation effort and victory over slavery. All that might have turned out for differently if the Defenses of Washington had not held on July 11 and 12, 1864 at Fort Stevens!

Years later, a Senate commission seeking parkland for a burgeoning city ensured that at least some of the forts and their undeveloped landscape would form the basis of a fort circle park system to benefit residents with fresh air and green space. More recently, Virginia jurisdictions have saved the last remaining vestiges of these sentinels of another era. Nonetheless, today’s Defenses of Washington remain high on preservationists “endangered species” lists. True, a Civilian Conservation Corps reconstructed Fort Stevens’s parapet and magazine. These, together with nearby Battleground National Cemetery, give posterity a sense of this forgotten field of strife despite niggardly interpretation and the complete absence of a visitor’s center for comprehending the magnitude of the people and events and people that took place there. The McMillan Commission efforts to use remaining forts as core elements for urban parkland provided an important precedent. The legacy of these efforts, however, is troubled. The survivors of the once-mighty Defenses of Washington are attended by overgrown earthworks, abandoned trash, poorly interpreted historical remains and plagued by questionable public safety.

Today’s tourism could profit from the McMillan and other preservation efforts concerning the Defenses of Washington. Key survivors provide something “beyond the National Mall” for visitor experience in the Nation’s Capital. Happily, they include Alexandria’s city-run Fort Ward Museum and Park, offering reconstructed earthworks and the only true visitor’s center devoted to the topic. Arlington County’s Fort C. F. Smith and the National Park Service owned Fort Marcy off the George Washington Parkway or Fort DeRussy in Rock Creek Park suggest prime un-restored but preserved examples of the forts. Other fragments remain scattered around the city, but some of the best languish east of the Anacostia River in neighborhoods of dubious access due to crime. The better maintained if under-interpreted Fort Stevens in northwest Washington and the fascinating river fortifications in southern Maryland — old Fort Washington and its state-of-the-art Civil War successor, Fort Foote — make ideal tourist destinations. In fact, visitors to the latter will be treated not just to the formidable earthen parapets and sophisticated design for withstanding heavy naval attack, but solid interpretive markers and two remounted seacoast Columbiad cannon add a uniqueness rarely found elsewhere. Battleground National Cemetery near Walter Reed Army Medical Center on Georgia Avenue, NW, and Fort Stevens have recently been joined by a new heritage walking trail in the adjacent Brightwood neighborhood, dealing heavily with the battle, make the area worth a special pilgrimage.

So today at the remaining defense sites, dog parks vie with picnic areas, overgrown earthworks and trash-littered parkland supplement wildlife and city life creatures. Biking and hiking trails plus urban streets afford access without much direction, and the only randomly interpreted forts all muster a full spectrum of challenges for stewards of the Civil War forts of Washington. In the end, we would do well to remember an American president was under fire an nearly lost his life at one of these sites, together with many of his boys in blue; a Medal of Honor was earned here; and the combined efforts of white and black, soldiers and civilians kept tenacious Confederate troops at bay. The forts and their modern green space are just as worthy of preservation as any battlefield. Because of them, Washington, D.C. — the symbol, sword and shield of one nation — emerged unscathed from the Civil War and stands today as the centerpiece of our heritage.