Louisa May Alcott. If her name rings a bell, it is likely that images of a cozy New England landscape, the eclectic March sisters, or ink-filled pages ran through your head. As the beloved author of “Little Women,” Alcott crafted a story that gave readers insight on the northern home front during the Civil War — whether it was through the March family’s involvement in the local war effort, the worry they expressed for the home’s patriarch during his time fighting for the Union, or the mother venturing to Washington to nurse said patriarch back to good health — as informed by her own wartime experiences. She also encouraged society to reflect on the bonds of sisterhood and family, the power of creativity, and the value in advocating for those less fortunate, among other themes. According to a National Geographic article from December 2021, it is estimated that more than 10 million copies of “Little Women” have sold in the years since its publication in 1868, with translations in at least 50 languages.

But, more than the author of a story that has met screens big and little and touched the hearts of ‘little women’ across time, Louisa May Alcott was a woman whose ideas and beliefs went beyond the confines of her written works.

Raised by two idealistic transcendentalists alongside her three sisters, Alcott lived in a spirited world, surrounded by encouragement to learn and seek creativity and self-expression in reading and writing. But she also felt an obligation to support her family during financial woes, to stand up for causes she held dear, and also to maintain her sense of individualism. Above all, she saw the troubles that plagued those around her and refused to stand idle.

Louisa, Loyal to Her Causes

A product of her upbringing, Alcott was a constant witness to the antislavery work of her parents. Her father, Bronson, had even founded an abolitionist society in 1850, and her childhood home — “the Wayside” in Concord, Massachusetts — served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

It was this dedication to seeing the end of slavery that largely propelled Louisa May Alcott’s commitment to the Union war effort. At first, her support was simple — sewing and mending Federals’ uniforms or tending to their minor needs. But her desire to contribute to the cause grew...

Ms. Alcott Goes to Washington

With her eyes wholly fixated on the larger impact she could make, Alcott departed Concord to work as a nurse for the Union in Washington, D.C., in December 1862. She came with a glowing recommendation from a respected nurse and a heart “full of hope and sorrow, courage and plans.” It was also noted that when Alcott left, her father remarked that he was "sending his only son to war."

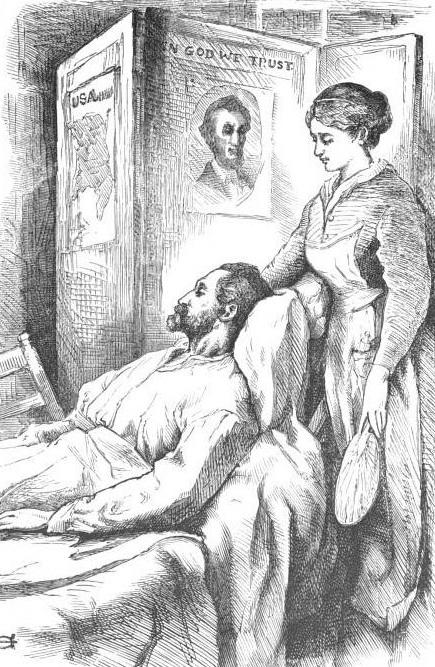

She landed at the Union Hotel hospital in the Georgetown neighborhood, where she threw herself into work. Her days were consumed with dressing wounds, cleaning and sewing bandages, supervising convalescent patients, fetching bed linens, water, and pillows, assisting during surgical procedures, sponging broken bodies, writing letters on behalf of the sick and injured, and feeding those too weak to feed themselves.

She developed a deep fondness for several patients, especially Mr. John Suhre, a blacksmith who had been gravely wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 11–15, 1863). Recording many of her experiences, Alcott expressed how moved she was by his quiet dignity and devotion to his mother, and how she was drawn to his “most attractive” and “comely featured” face. So, when she was tasked by the hospital surgeon with telling Suhre that his injury was fatal, she found composure difficult. She later wrote, “Such an end seemed very hard for such a man. The army needed men like John, earnest, brave, and faithful; fighting for liberty and justice with both heart and hand, true soldiers of the Lord.”

Despite the devastating nature of the work, nursing filled Alcott with excitement and purpose. Seeing her efforts in correlation to the cause of abolition, she wrote, “My greatest pride is that I lived to know the brave men and women who did so much for the cause, and that I had a very small share in the war which put an end to a great wrong.”

Louisa’s “Hospital Sketches”

However, passion for the work could only carry Alcott so far — her body had its limits and 12-hour shifts, poor diet, and inadequate ventilation were taking their toll. By mid-January, she was unable to work, confined to her room, and diagnosed with typhoid pneumonia. The hospital’s doctors and nurses, along with Army Superintendent of Nurses Dorothea Dix, all encouraged her to return home. Her family was eventually alerted by telegraph, which prompted Bronson Alcott to rush to collect his sick daughter in the capital.

Yet, Alcott’s experiences as a Civil War nurse continued on in her writing. The journal she kept and her many letters home formed the inspiration for “Hospital Sketches” — a series of slightly fictional stories told through the lens of Nurse Tribulation “Trib” Periwinkle within the chaotic setting of the “Hurly-Burly House” where she worked.

With an informed perspective, Alcott gave voice to “Nurse Trib” as she navigated the pell-mell streets of Washington, D.C., filled with soldiers and contraband, as well as the bustling hospital by day and eerily quiet wards by night. “Nurse Trib” provided a balanced view of her work, speaking to tender friendships and rewarding working partnerships but also altercations with arrogant and old-fashioned surgeons who disliked the presence of the untrained female nurse. She also accounted for many of the heartbreaking encounters with patients that Alcott herself contended with.

The stories were first published, little by little, in a Boston-based abolitionist magazine Commonwealth throughout May and June 1863. Later that year, they were published as one whole collection by James Redpath, providing a springboard for Alcott’s later success with “Little Women.”