Did you know that during the Civil War years, thousands of letters home went undelivered?! Did you also know that thousands of them contained soldier photographs? What happened to the letters? And, more so, what happened to the photographs? The answer is quite “head-tilting!”

During the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of young men wrote letters home. But many were poorly educated or had never even addressed a letter, therefore yielding several undecipherable envelopes. Sweeping changes to postage requirements and the interruption of mail in the seceded states also heavily impacted the delivery of letters. Those letters that could not be delivered were processed by the Dead Letter Office.

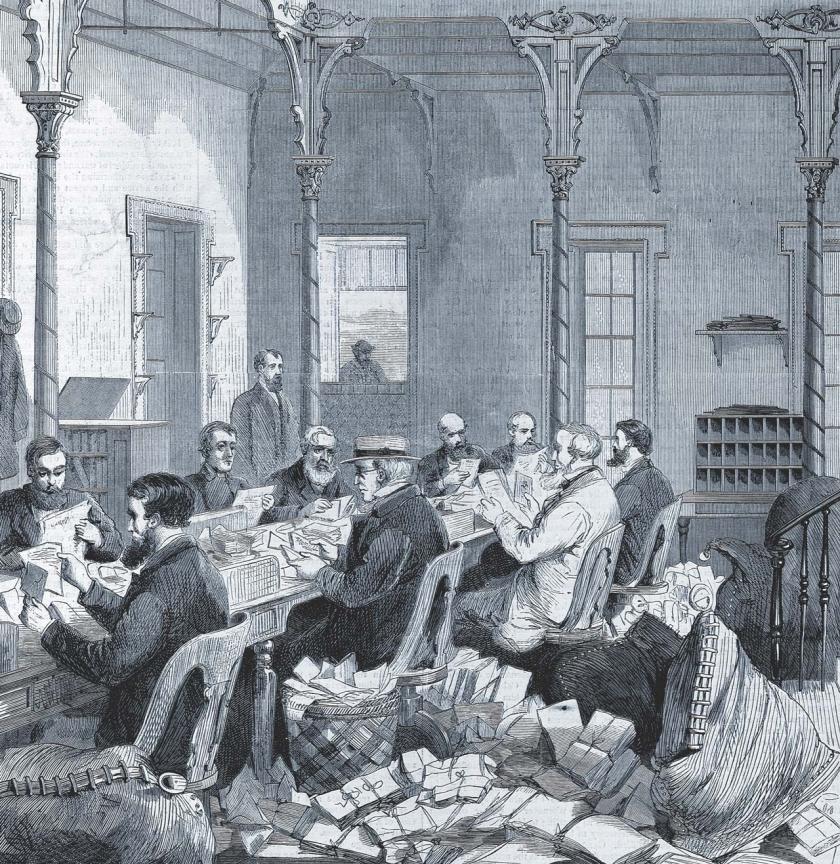

Established in 1825, the Dead Letter Office (DLO), located in Washington, D.C., was designated to investigate undeliverable mail, with the intent of distributing it to its intended recipient. DLO clerks were exclusively granted by Congress the ability to open mail to examine its contents for further clues on its destination. During the mid-19th century, most of the dozen or so DLO clerks were women and retired clergymen, believed to possess a superior moral character and could therefore be trusted with the cherished contents of these dead letters.

Great care was taken to protect and return as many letters as possible, especially those of any monetary value. For items such as advertisements or circulars, or those that were never claimed or could not be delivered, the clerks oversaw their disposal — except Civil War soldiers’ photographs. While these items technically should've been disposed of, according to Lynn Heidelbaugh, a curator at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, they never were. And, driven by a sense of patriotism or devotion, the DLO continued its attempts to reunite them with their intended recipients, even long after the war ended.

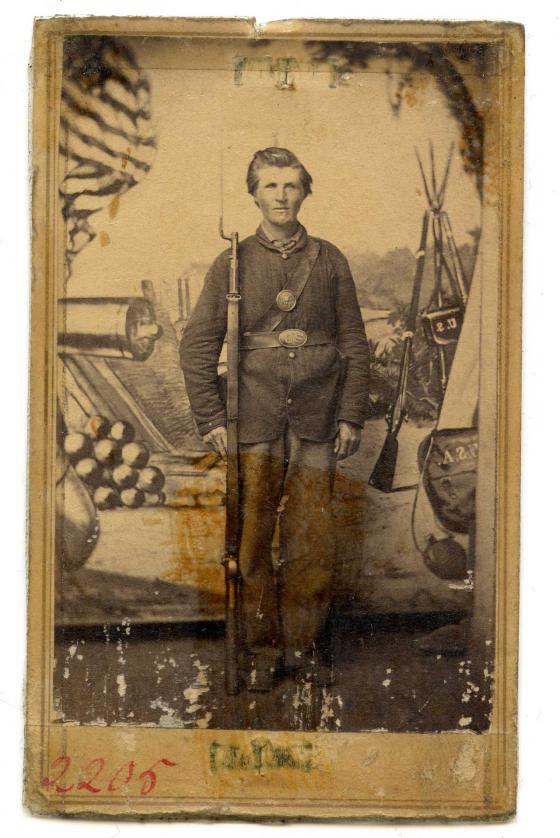

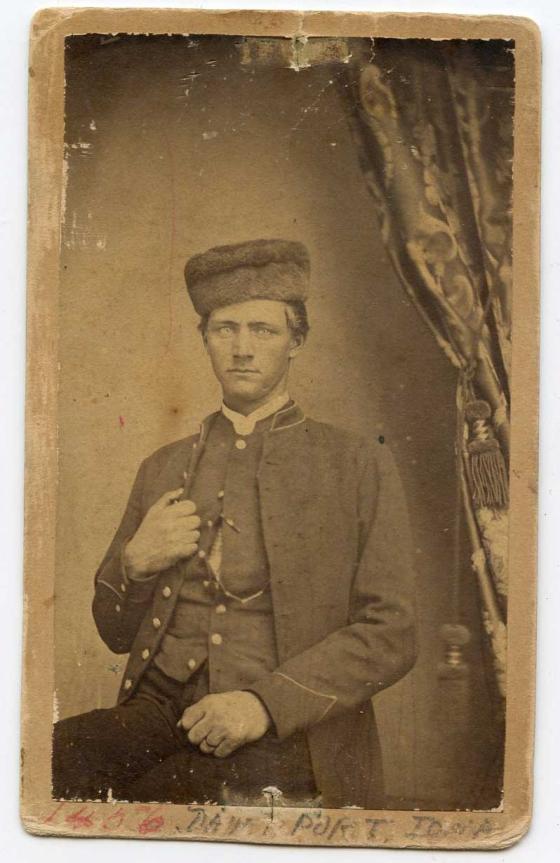

Enclosed with letters home, the photographs came in the form of cartes-de-visite or tintypes. Many were portraits of a single soldier, but some posed with a comrade or two.

By the end of the conflict, thousands of these photos remained undelivered, with most estimates around 5,000. They lingered in a portfolio of sorts in a Post Office storeroom, with little hope of finding their destination — that is, until Third Postmaster General Alexander Zevely, who served from 1859-1869, conjured up an innovative idea: display them in the Dead Letter Office Museum.

“Crowdsourcing” Long-Lost Images

The Dead Letter Office Museum housed an eclectic combination of items that represented both the Post Office Department’s history and showcased some of the more curious objects that passed through the DLO each year, including unusual trinkets, pistols, various bottles and boxes, and even a skull.

The museum was an oddity and a popular tourist attraction, which Zevely hoped would help put more eyes on the soldiers' images. You could call it crowdsourcing! At his request, the portraits were attached to panels with brass clips in groups of 36 images, or four rows of nine images each, and numbered with red-ink numerals.

Museum visitors would scan the image panels and the thousands of stranded faces they displayed, seeking a brother, a husband, a father, a neighbor or a sweetheart — often one lost to the war. The display itself was a moving tribute to the servicemembers who had sacrificed years, and sometimes their last full measure of devotion, to the Union.

When a familiar face presented itself, a loved one would claim it by number. Then, a clerk would remove the image from the board and write in its place the date of its removal and the name and location of the person receiving the image. On June 17, 1874, Mr. F. Poplain claimed the photo of Lieutenant S. Roderick of the 19th Iowa Infantry, according to an extant panel. On October 16, 1902, Edward Marsh of the 10th New York Battery claimed a photo of himself, some 40 years after he had placed it in the mail. It is impossible now to say how many of these often-emotional reunions occurred, but some estimates put the number as high as 2,000.

The Dead Letter Office also advertised descriptive lists of the photographs in newspapers and journals of the Grand Army of the Republic. In the early 1890s, the photographs and panels were cleaned and bound into an album, one panel per page.

These extraordinary efforts to reunite the soldier photographs with their recipients went “above and beyond the standard operating procedure” of the DLO, says Heidelbaugh. “I think it shows how deep the scars of the war were for the United States and that people were dealing with the aftermath very personally and in a very tangible way.”

A Travel-Friendly Format Yields More Reunions

Bound in an album, these photographs could be easily transported. Propelled by the album’s travel-friendly nature, the Dead Letter Office took the opportunity to exhibit it at world’s fair exhibitions across the country, enabling new sets of eyes to peruse the thousands of soldier photographs that remained unclaimed. The fairs provided a handful of new success stories but, with several decades since the war had taken place, they were few and far between.

In 1911, the Dead Letter Office Museum closed and the album lingered in the Dead Letter Office for a time, still available for the then-infrequent observer. By the 1930s, it was placed in storage. Then, in the 1940s, the government decided to free up storage space at the Post Office building and the album was divided and sold. Some are housed in museums. Many more turn up on the collector’s market still, with their tell-tale red numerals and markings where the brass clips had once secured them to them to the walls of the Dead Letter Office Museum.