The Whiskey Rebellion

Just years after the successful American Revolution and the creation of the United States of America, rebellion occurred. This insurrection proved to be the first of many tests that the infant nation had to deal with. However the government decided to react to this crisis, precedents were to be set for future leaders of this country. As such, the stakes were high for the United States government during this tense time.

Following the Revolutionary War and the creation of the Constitution, the federal government of the United States consolidated all war debts from each of the former colonies now referred to as states. This mounting national debt required action, and Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, began establishing taxes in order to clear the nation’s debts. Hamilton, believing that the newly established import duties were as high as they could be, decided that additional revenue was to be collected by the manufacture of whiskey. This new act taxed the manufacture of a product rather than the sale of a product and was the first federal tax on domestic products in the United States. Many Federalists believed that this new tax acted more of a “luxury tax” and did not have the ability to anger many citizens and advocated its passing in Congress where it was eventually passed as the 1791 Excise Whiskey Tax.

However, the Federalists failed to realize that whiskey production was held in high regard within the western frontier, specifically in western Pennsylvania. Many families that lived on the frontier relied on grain farming for food and income. Additionally, many grain farmers used the surplus grain to ferment and distill into whiskey in their home stills. Furthermore, many grain farmers preferred producing and trading whiskey rather than transporting and selling raw grain. Many families on the frontier even used whiskey as a form of currency, as many traders and other frontiersmen did not have cash or other forms of money and resorted to bartering and trading whiskey. Moreover, many grain farmers simply preferred the transportation of whiskey rather than raw grain, as many of the roads were poorly developed and whiskey could be transported longer than raw grain. Also, whiskey was more profitable than raw grain, and frontiersmen could transport more whiskey than they could raw grain so the whiskey trade was more appealing.

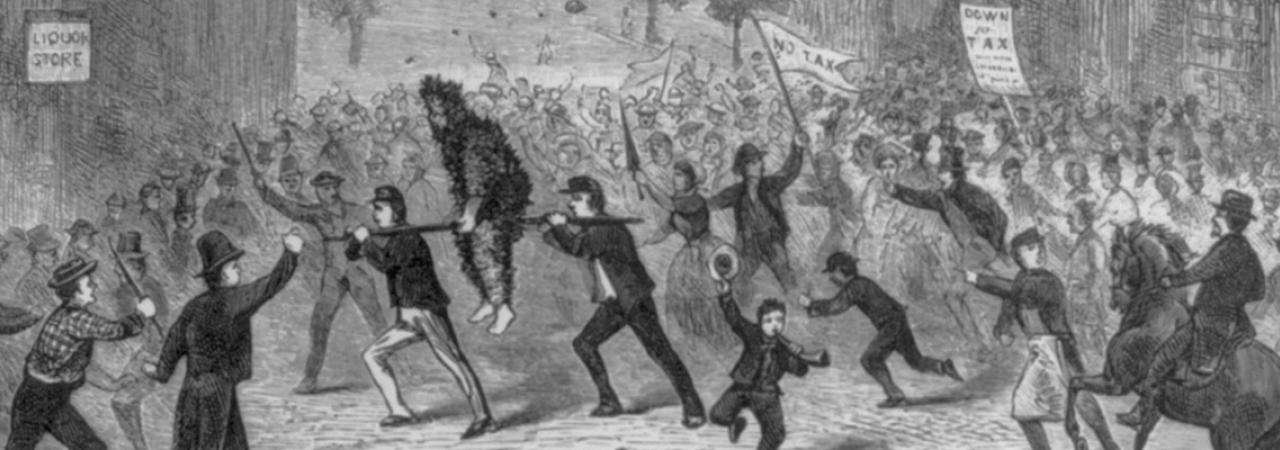

Many families on the frontier saw this tax as an affront to their livelihoods, as the whiskey trade was vital for their survival. As a result, many of these small family-owned distillery operations began to feel resentment against the current regime, believing that the Washington administration was just as tyrannical as the English Parliament they had, just fought to establish their own new and independent nations. Thus, protests began in western Pennsylvania against the perceived elitist tax as the stills in the frontier had to work harder to produce and transport their grain products for sale. The issue of transportation was virtually non-existent for larger whiskey distilling operations in urban eastern centers. Additionally, the tax on whiskey was regressive, meaning that the more a distiller produced, the less they had to pay in taxes. The regressive nature of the tax disproportionally hurt the small distilleries owned by families on the frontier. Additionally, the tax was to be collected in cash, which many simply did not have on the frontier. This tax was poised to upset the entire market of bartering and trading that was established on the western frontier. To protest the tax, those on the frontiersmen simply refused to register their stills with the government. In order to combat the operation of unregistered stills, the federal government relied on local tax collectors and other locals to help locate the small stills on the frontier. As a result, many grain farmers and whiskey distillers lashed out at local “collaborators” and tax collectors, resorting to the tactics of the American Revolution. Tax collectors were being threatened and even tarred and feathered, all while public demonstrations began increasingly violent, local militias were being formed for the purpose of fighting this tax.

The violence finally boiled over in the summer of 1794 when local tax collector and landowner John Neville aided a federal marshal in the serving of writs. On July 16, 1794, a large mob of rebels gathered outside Bower Hill, the house where Neville was sleeping. Neville confronted the crowd outside his doorstep and shot one of the rebels out of fear for his life. Neville retreated into his house and began fortifying it with the help of his slaves. The mob of rebels only grew throughout the night. At the same time, ten federal soldiers arrived at Bower Hill to reinforce the house and escort Neville to safety. By the morning, around 700 armed insurgents surrounded the house and demanded the surrender of the defenders. The mob agreed to let the women and children inside the house leave unharmed before the hour-long firefight began. After the hour of fighting, three militiamen, including the rebel commander James McFarlane who was a veteran of the Revolutionary War, were killed along with one possible federal soldier, the rest of the soldiers inside the fortified house surrendered and were taken, prisoner. The militia subsequently burned the estate on Bower Hill and marched off to Pittsburgh a week after the firefight. The insurrection wanted revenge for McFarlane’s “murder” as they believed it to be. By August 1st of 1794, around 7,000 rebels were gathered at Braddock’s Field, only 8 miles away from Pittsburgh, and were beginning to make plans to attack the city. To buy time, the city’s government attempted to call negotiations with the rebels while the federal government could respond.

President George Washington, in accordance with the Militia Act of 1792, received permission from Supreme Court Justice James Wilson to raise an army to combat the rebellion in western Pennsylvania. With the help of Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee and Daniel Morgan, President Washington now was in command of 12,950 federal soldiers to crush the rebellion on the frontier. As the army marched towards western Pennsylvania, to meet the rebels, Washington personally rode to review his soldiers in September of 1794. This was the first and only time a sitting United States President ever led soldiers in an active campaign. By October of 1794, the federal army was closing the distance with Pittsburgh, resulting in the collapse of the rebellion, as many began to flee for safety from the massive federal force. The leaders of the insurrection fled into the frontier while the federal army began arresting suspected members of the rebellion.

When the dust had settled, approximately 20 people were indicted for their roles in the rebellion. Only ten people stood trial, however, and only two were convicted of treason. Much to the dismay of Alexander Hamilton, who wanted to see more punitive measures taken against rebels to the United States. In an effort to show clemency and the fact that these two convicted traitors played a minimal role in the rebellion, President Washington pardoned the two convicted individuals during his Seventh State of the Union Address.

Further Reading